How government reshuffles go wrong – and why it happens so often

Some reshuffles are planned well in advance and some are sudden but they all have the potential to go off-course.

Some reshuffles are planned well in advance and some are sudden but, as Catherine Haddon explains, they all have the potential to go off-course.

Reshuffle day means uncertainty across Westminster

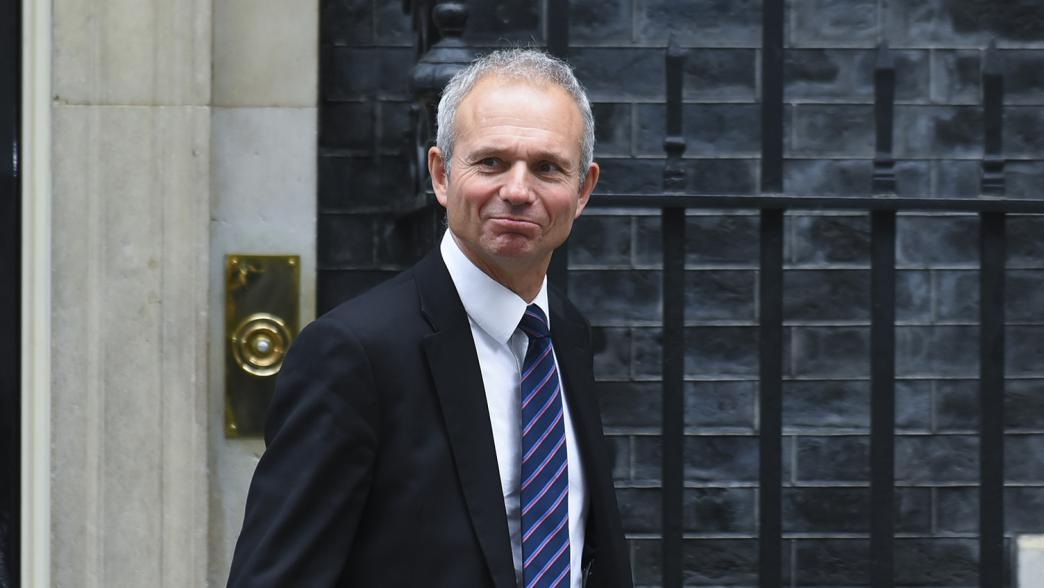

MPs can be stuck in strange places when they receive the Number 10 phone call. Gavin Barwell was ‘halfway up a tree, cutting down a branch’; Ben Gummer was at the cricket. David Lidington had to stop at Watford Gap services to take the call. Jeremy Browne sought out a train toilet so he could talk to the PM with some privacy.

Many have no idea what that all-important call will bring. As Barwell, a former No.10 Chief of Staff, puts it: ‘You can either just be left, not get a call at all and just stay where you are, or you go down or you go up, and you don’t know when the call comes what it’s going to be’. Newspapers and twitter are full of speculation. Very few outside a tiny circle in No.10 know for sure. When Nicky Morgan was moved from the Treasury to become education secretary in 2014, ‘there wasn’t even speculation… because I really didn’t think I was on the radar for a promotion.’ Peter Mandelson’s phoenix-like return to government in 2008 was a move few saw being made by Gordon Brown.

Occasionally ministers get an inkling. When Liam Fox resigned from the MOD in 2011, Philip Hammond heard he was a likely replacement. When he finally got to speak to the PM, Hammond pretended to that it was unexpected – difficult to do when the line kept cutting out.

Reshuffle decisions are too rarely about ministerial performance

No.10 has said the PM will judge ministers on performance. But it tends to be a complex mix of factors. Former Liberal Democrat minister Michael Moore has said that ‘you will get ministers who will be regarded as under-performing but can’t be sacked. You will get others who do brilliantly but, because they don’t have political weight in the party, they can go’. Some ministerial departures are simply about making way for new blood.

Margaret Beckett thought she was moved in 1998 because she had angered Gordon Brown at the Treasury, and because Peter Mandelson was eyeing up a move to the Cabinet. "The prime minister at that time had two best friends, " Beckett recalled. "One wanted my job and the other one wanted me out of it".

PMs take advice. This can be from chief whips – not always a disinterested party, as Gavin Williamson’s controversial 2017 promotion from chief whip to defence secretary showed – and party veterans, with Tony Blair apparently enjoying the views of backbencher Dennis Skinner. Even the government drivers have sometimes been canvassed.

Reshuffles are likely to go off-course at some point

Inside No.10, reshuffles start with a whiteboard and continue with a rolling email chain to choreograph the day, particularly the awkward shuffling of ministers in and out of different No.10 waiting rooms. Everyone tries to make sure a key person isn’t forgotten or a role accidentally unfilled. But plans go wrong. In May 2003, Chris Mullin replaced a minister who resigned over Iraq, with Blair forgetting that Mullin had also voted against the war. According to his chief of staff Jonathan Powell, by the time they realised ‘it was too late as he had the job already’. In January 2018 Chris Grayling lasted less than ten minutes as Conservative Party chair after the party HQ mistakenly tweeted out his (non) appointment.

PMs throw in last minute surprises. In 2001, Jack Straw expected to get John Prescott’s Environment, Transport and the Regions job, with Charles Clarke given the Foreign Office. But Clarke’s troubles at the Home Office meant a change of plan. When Blair told Straw that he was being made foreign secretary, a shocked Straw swore and nearly fell off his chair.

The biggest problem is when a minister dares the PM to sack them. In June 2007, Alastair Darling threw Gordon Brown’s reshuffle into confusion when he rejected a move from the chancellorship. Andrea Leadsom failed to do the same in July 2017, when she pushed back against May’s attempt to move her from Defra to leader of the House (she reportedly wanted Home Office). When Jeremy Hunt refused to quit as health secretary in January 2018, he thought he ‘was probably going to be ending my career in cabinet’. He waited outside the room until May figured out how to respond. Hunt kept his job.

Even after the reshuffle, PMs might not remember who they appointed. In late 2007 Gordon Brown called Shriti Vadera, the former investment banker brought into government as a Lords minister, to ask her advice on the brewing financial crisis. Vadera answered that she was currently in Africa. A confused PM asked why, leaving Vadera to explain that Brown had given her a job at the Department for International Development. A few months later she was moved to the Department of Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (BERR). .

An unhappy departure can cause lasting damage

Reshuffles can create political enemies, and most PMs dislike sacking their colleagues. This process usually happens in the PM’s offices in the Commons. It can be an awkward moment. There are stories of ministers who weren’t entirely sure they were out because the PM was so vague. Gisela Stuart says the only time Tony Blair pronounced her name properly was when he sacked her.

With TV cameras watching everyone coming and going from Downing Street, it is hard to keep bad news a secret. George Osborne left by the back door after Theresa May sacked him as chancellor, but the optics don't change the story.

A good reshuffle is a chance for a PM to look commanding. A bad one can turn the tables on his or her premiership. In the end, for all the planning and precision, most reshuffles end up somewhere in between.

- Supporting document

- government-reshuffles.pdf (PDF, 1.11 MB)

- Topic

- Ministers

- Series

- Ministers Reflect

- Publisher

- Institute for Government