Let us hope these emergency cash injections for social care are coming to an end

Councils need confidence about future funding to invest prudently, but cash injections are stop-gap solutions.

The £240m to alleviate winter pressures announced by Matt Hancock won’t confront the real problems in social care, says Graham Atkins.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock told the Conservative Party Conference that the Government will provide an extra £240m for councils to provide social care in England. This money is intended to help patients who are fit to leave hospital but have nowhere to be cared for. But this money – 1.4% of what councils had planned to spend this year anyway – is considerably less than a third of what independent analysts think is needed to meet current needs. Cash injections are always welcome in the short term, but repeated cash injections are counterproductive. Councils need confidence about future funding to invest prudently, but cash injections are stop-gap solutions. They make it hard to invest to address real problems such as rising staff turnover and care homes’ financial sustainability.

With Brexit consuming the Government's time and political capital, a cross-party inquiry is still the Government’s best hope to reform social care funding and provide councils with the financial certainty they need to plan ahead and address these problems.

£240m won’t meet social care demand this winter

Mr Hancock suggested that the £240m announced will be given to councils to “to get people who don’t need to be in hospital, but do need care, back home”, suggesting he wants them to spend it on care in people’s homes.

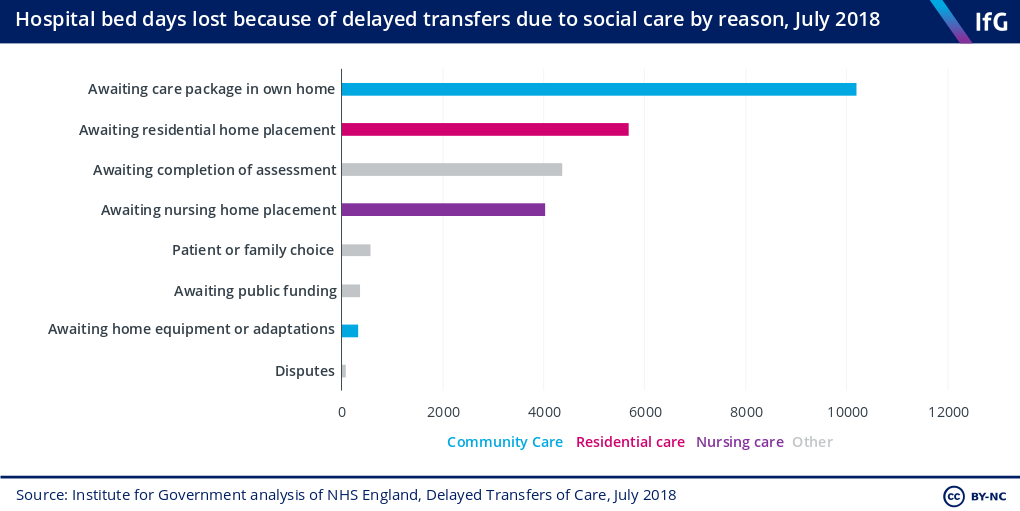

This is sensible. In July 2018, 41% of hospital bed days lost due to social care were because patients were waiting for a care package in their own home, and research suggests older people want to remain in their homes as long as possible. But £240m won’t buy enough home care packages to meet demand. Estimating how much would be enough is difficult, but independent analyses suggest that there is an annual gap between government spending and social care needs of between £900m and £2500m.

If the money is intended to relieve hospital pressures, some will have to be spent on residential and nursing care. 38% of hospital bed days lost due to social care are attributable to lack of nursing and residential places, almost as many as community care.

Emergency cash injections have made it hard to address real social care problems

The amount of money is not the only problem. The way the Government has given money to social care since 2015 – injecting emergency cash in the face of political or operational crises – is just as big a problem. The Government has now given social care one-off cash top-ups each year for the last four years. This is ineffective. It makes it hard for councils to address underlying problems because they cannot be sure how much money will be available for them to spend on adult social care next year.

Our analysis from Performance Tracker – produced in partnership with the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy – found two particularly prominent problems: staff retention and the financial sustainability of the care providers in the private and voluntary sectors.

Social care struggles to retain staff. 37.5% of care workers – the staff who provide frontline care – left their job in 2017/18, up from 28.4% in 2012/13. A one-off emergency cash injection for councils to provide care packages over the winter will not be enough to convince providers – who employ care workers – to invest in training opportunities which could improve staff retention.

Equally pressing, providers look less financially sustainable more generally. Earlier this year, the Competition and Markets Authority found that local authorities were paying approximately 10% below the total cost of care home placements, and that most care homes were now only investing to build places for people who can pay for their own care. A one-off cash injection is unlikely to be enough to convince care homes to invest to build places for council-funded clients.

A cross-party inquiry remains the Government’s best chance of addressing these problems

To his credit, Matt Hancock recognised that £240m wouldn’t be enough, and promised the forthcoming social care green paper – a Government consultation on the future of social care – will tackle these problems. But the green paper has already been delayed three times. Originally due to be published in the summer of 2017, it is now due out some time this autumn.

With Brexit consuming time the Government could otherwise have spent on domestic policy, a better approach would be to set up an independent, cross-party, inquiry on social care funding, as we recommended earlier this year. This would be the best mechanism for the Government to build the political and parliamentary support it needs. Reformed funding would give councils, and the providers they purchase services from, the financial certainty they need to plan ahead and address underlying problems.

- Supporting document

- 5991 IFG - Performance tracker Autumn 2017 update.pdf (PDF, 2.14 MB) IFG_Funding_health_and_social_care_web.pdf (PDF, 900.32 KB)

- Topic

- Public services

- Keywords

- Social care Public spending

- Department

- Department of Health and Social Care

- Publisher

- Institute for Government