What did we learn from Boris Johnson’s February mini-reshuffle?

The prime minister has moved some key members of his team around in an effort to ‘reset’ No.10

The prime minister has moved some key members of his team around in an effort to ‘reset’ No.10 following the fallout of the Sue Gray update. The IfG assesses what this means for the government

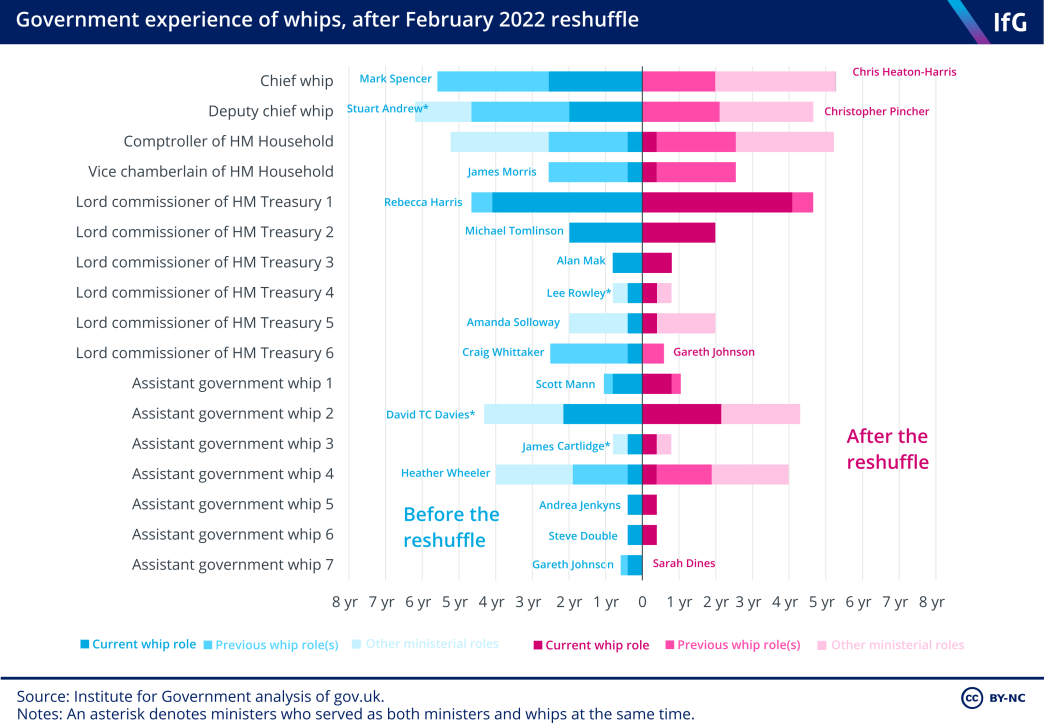

There is a new chief whip, but the Whips’ Office saw less change than expected

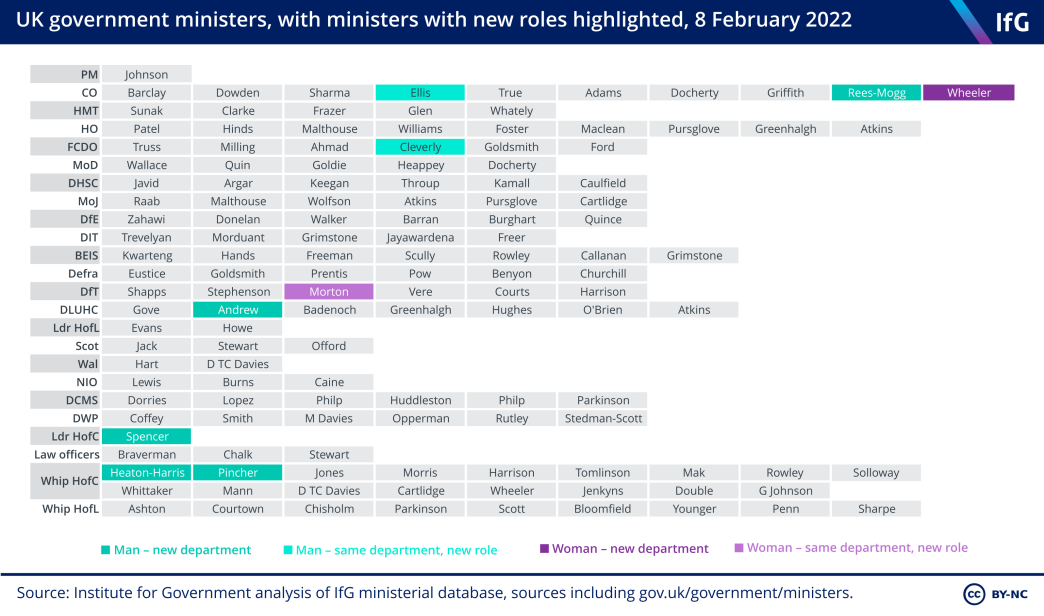

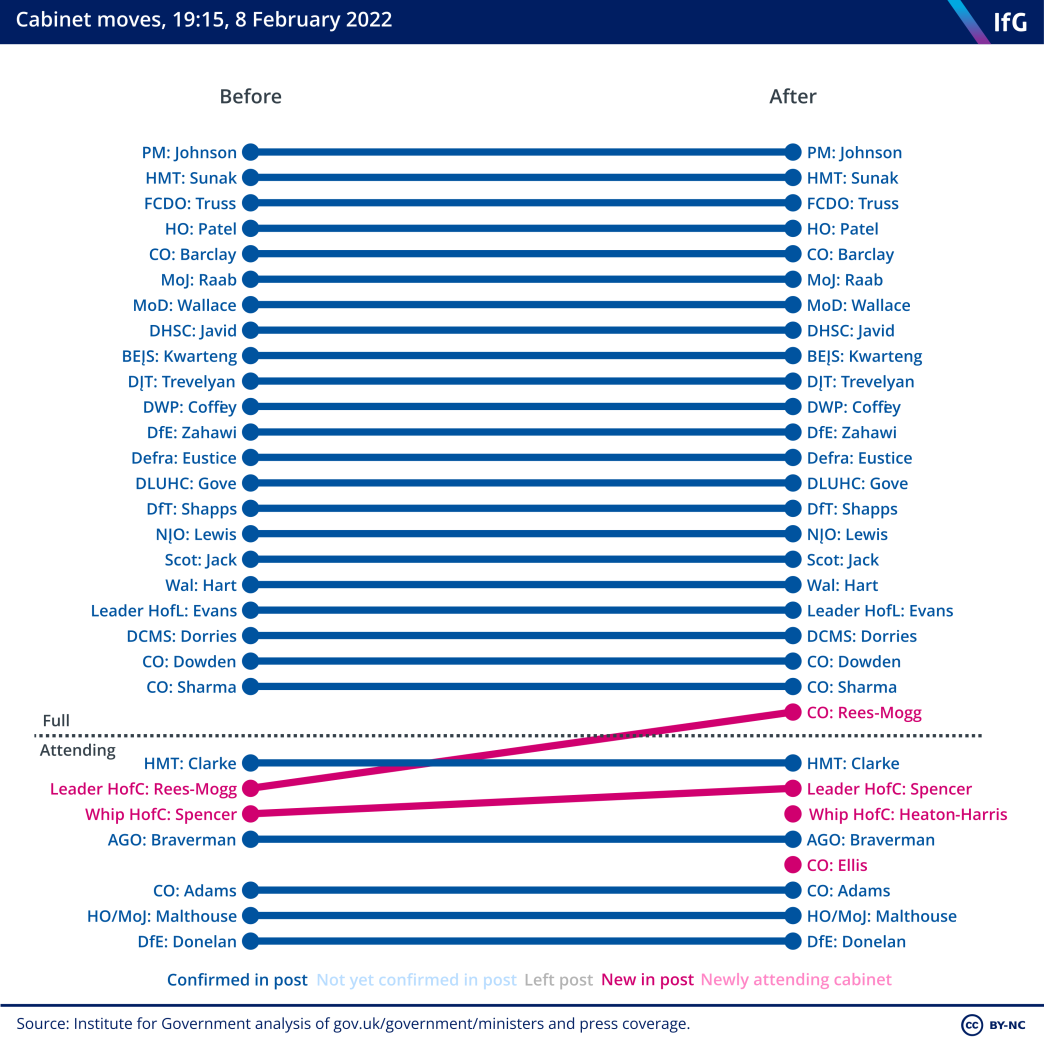

The outgoing chief whip, Mark Spencer, was criticised for handling of Owen Paterson affair and poor relations with backbenchers, and is under investigation for his role in the sacking of Nusrat Ghani in 2020. He has moved to become leader of the House of Commons, replacing Jacob Rees-Mogg, and his role passed to Chris Heaton-Harris, part of the recent “shadow” whipping operation to shore up support for Johnson. Heaton-Harris had served as a whip for several years before taking on departmental ministerial roles.

Spencer’s deputy chief whip, Stuart Andrew, has also been given a new role as housing minister at the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (making him the 11th postholder since May 2010; in a straight swap, Christopher Pincher has gone the other way, assuming the role from his position at DLUHC). However, despite briefing that there may be a clear out of the Whips’ Office more generally, most stayed in post.

Key Europe-facing roles have changed hands

The prime minister had been buffeted by resignations in recent months, including Brexit minister Lord Frost and transparency minister Lord Agnew. When Lord Frost resigned, most of his responsibilities – including for the UK–EU relationship and negotiations over the Northern Ireland protocol – passed to foreign secretary, Liz Truss. But the ‘Brexit opportunities agenda’ was left without a clear political champion. Jacob Rees-Mogg has now been appointed minister for Brexit opportunities (and ‘government efficiency’). As a strong proponent of Brexit, he has a personal interest in the brief.

Filling the gap left by Lord Frost should help restore momentum to the Brexit opportunities agenda, and signal to disgruntled Conservative backbenchers that the government intends to make use of its new-found autonomy. But Rees-Mogg will have his work cut out. The lacklustre ‘Benefits of Brexit’ white paper published last week showed that the government’s plans are still vague and ill-defined, with responsibility for delivering them split across government. It is also not yet clear if Rees-Mogg, who had not held a ministerial role before 2019, will have the political clout needed to bring his cabinet colleagues into line.

Heaton-Harris’s move to the Whips’ Office meant he had to be replaced as Europe minister at the Foreign Office. James Cleverly has taken on that role, having already been the Foreign Office’s Middle East and North America minister, a role which currently remains unfilled. The result of these moves is that there are two new ministers getting up to speed with the Brexit and Europe briefs at the same time the government is still working out how best to organise itself to manage the consequences of Brexit.

Questions remain over the relationship between No.10 and the Cabinet Office

The appointment of Steve Barclay as chief of staff at No.10 raised many questions. The reshuffle was an attempt to answer some of them, with the prime minister beefing up the Cabinet Office ministerial team. Michael Ellis, who has answered many awkward questions in the Commons regarding Downing Street parties on behalf of Johnson, has been rewarded for his loyalty with a promotion to minister for the Cabinet Office. Heather Wheeler, a whip, has also joined the department.

Presumably these new appointments are intended to take on some of Barclay’s responsibilities he will no longer be able to manage. But exactly how Barclay will work with the prime minister, and with other ministers at the Cabinet Office, is still unclear – not least on the question of who will answer for the department in the Commons.

Rees-Mogg is now part of the Cabinet Office ministerial team – as was his predecessor, Lord Frost. But he has also taken on the ‘government efficiency’ portfolio, presumably picking up the role Lord Agnew resigned from last month. This job will require attention to detail and a willingness to get into the weeds of government; we know Rees-Mogg wants to reduce the size of government, but can he help Barclay and Ellis reform it at the same time?

More of a ‘Heshuffle’

As with the changes to the No.10 team this was a male-heavy reshuffle. Heather Wheeler was appointed parliamentary secretary to the Cabinet Office and Wendy Morton promoted to minister of state in the Department for Transport but the main moves saw rewards or adjusted roles for some of the men who have supported and advised Johnson in recent weeks. And as both Wheeler and Morton were already in government, the reshuffle did nothing to improve the gender balance of the government.

Overall, the changes were limited

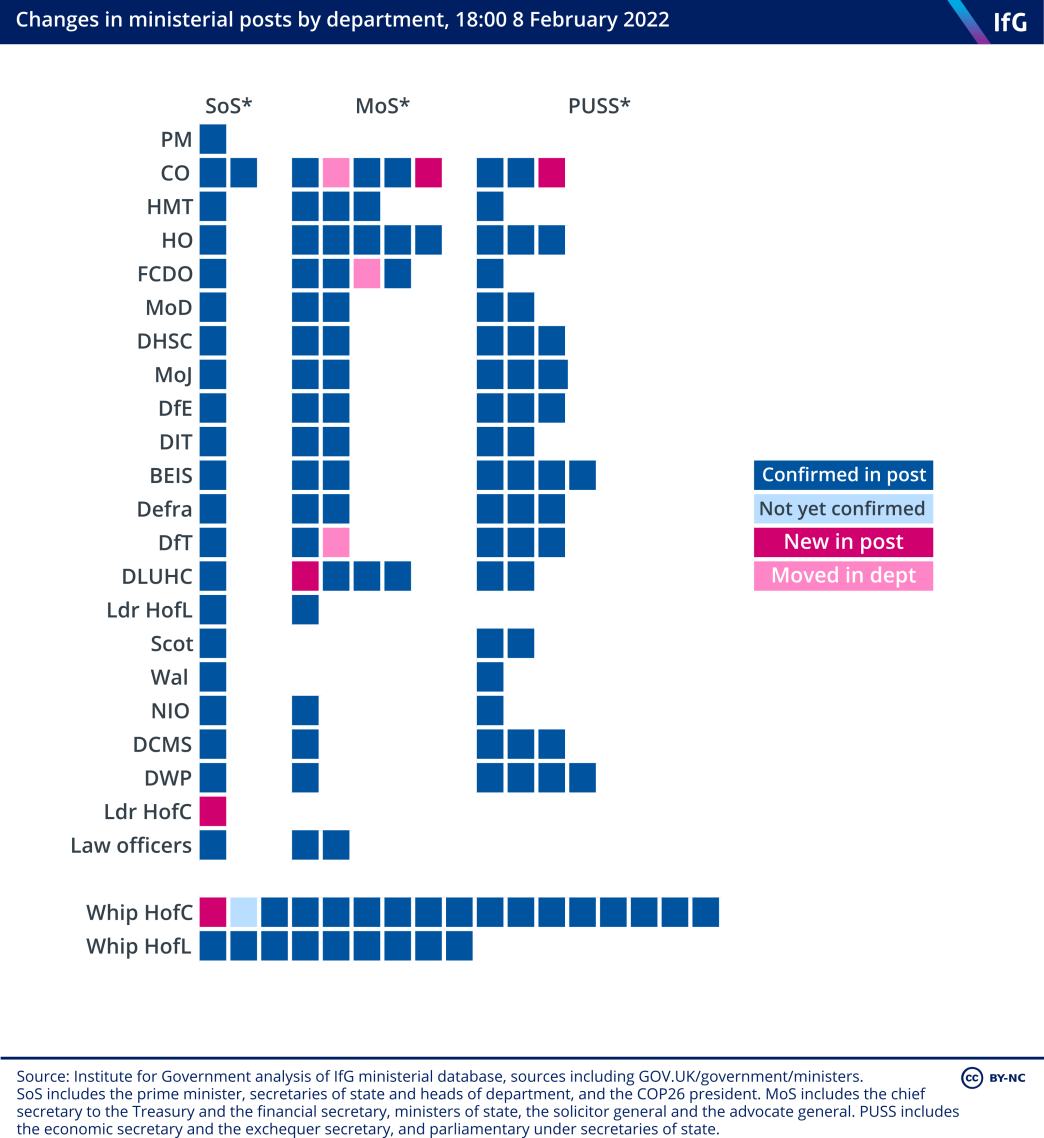

Given the more wide-ranging reshuffle in September last year it made sense to limit changes now. Beyond the few changes noted above, most of the others were backfilling the gaps they created.

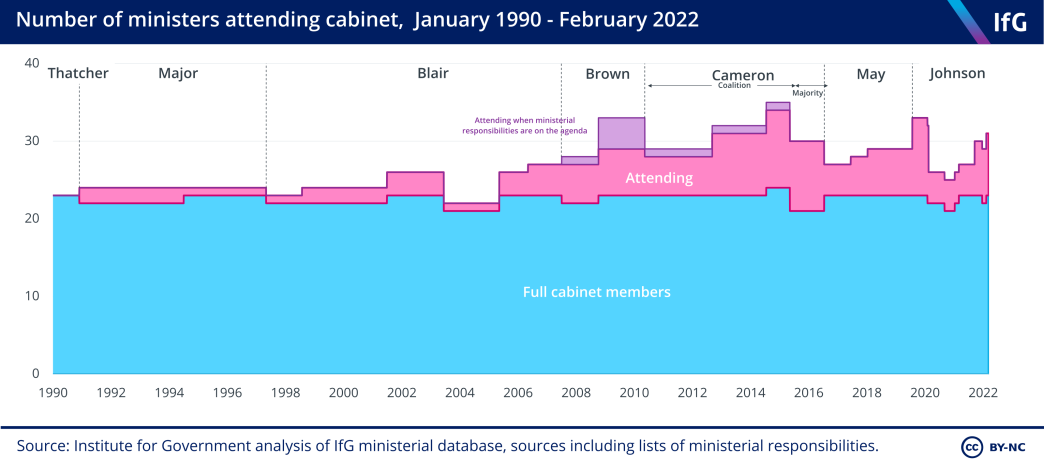

The only change among members of the cabinet was the somewhat surprising appointment of Jacob Rees-Mogg as a full cabinet minister in his new Brexit opportunities role. There was more change among the ministers who attend cabinet but are not full members, with Michael Ellis joining the list. The 23 members of cabinet and eight attending ministers means cabinet has continued to grow – having been at 25 in total after the 2019 election, the number now stands at 31.

At junior ministerial ranks, there was little change – some whips moved to new roles or took on a ministerial role alongside their whipping responsibilities.

The prime minister will hope this reshuffle allows him to get on with the job

Johnson promised his backbenchers change after the fallout of the Sue Gray update and he will point to this reshuffle as delivering that. The ministers that backbenchers interact with most often – the senior whips and the Leader of the House – have changed. And the expanded Cabinet Office team will be tasked with helping Johnson ‘get a grip’ on the centre of government (although they are unlikely to be able to change the way the prime minister himself works).

But it is a very Westminster reshuffle, which anybody beyond the bubble is unlikely to notice. The question – beyond whether these changes will actually smooth over the prime minister’s relationship with his MPs – is whether he has crafted his latest team more to manage the internal problems of his party than to deliver the real-world change he has promised.

Contributing authors: Tim Durrant, Catherine Haddon, Alex Thomas, Alice Lilly, Joe Marshall, Philip Nye and Paeony Tingay.

- Supporting document

- government-reshuffles.pdf (PDF, 1.11 MB)

- Topic

- Ministers

- Keywords

- Government reshuffle

- Position

- Prime minister

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Department

- Cabinet Office Whips' Office

- Public figures

- Boris Johnson

- Publisher

- Institute for Government