The changing structure of public spending – accident or design?

If we are back in the world of "boom and bust", we need to think about how our public finance frameworks operate in a world of large cyclical swings.

In 2006/07, I suspect very few people would have agreed that the government should:

- increase the share of our national income spent on pensioner benefits, the NHS and overseas aid through reduced spend on education, law and order, defence

- in the event of an unexpected recession, finance the interest on the debt through further reductions in these same areas.

However, this is exactly what the Coalition government has done.

How state spending is shifting

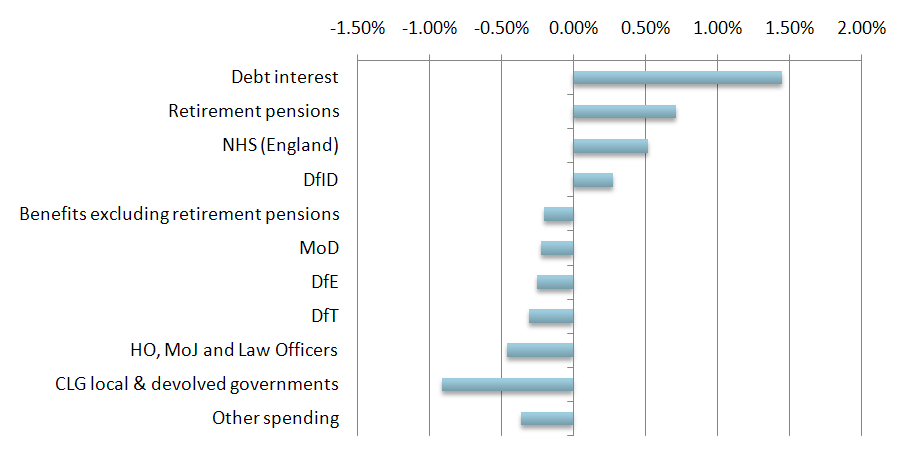

The last government’s decision to stick to the fixed cash spending plans that emerged from the 2007 spending review, together with the (explicit and implicit) ringfences in last month’s spending review, have changed the structure of public spending. I've been playing with the numbers and have now got some figures to illustrate the effect. Commentators have focused on the scale of reductions implied by the Spending Review. But expected spend as share of GDP in 2014-15 (41.0%) is almost identical to actual spend in 2006-7 before the recession (40.8%). But what this disguises is a big shift in what we spend our money on:

- on the way into the recession, sticking to the cash plans meant big effective increases in spend, with health, education and benefit recipients as big winners

- on the way out of recession, ringfencing helps protect health, pensioners and international development.

This graph shows the resulting percentage point GDP changes in spending between 2006-07 and 2014-15:

Expanded areas are:

- debt interest

- retirement pensions (the basic state pension and SERPS)

- health (for now, we can only do the England numbers as the rest depends on devolved governments)

- international development.

To finance these, there are big contractions in law and order departments and local government. MoD, DfE and DfT all take serious hits (especially DfT given its relatively small baseline).

Accident or design?

The question I am asking is whether these changes illustrate a "time inconsistency" problem in policymaking, whereby decision-makers make the best decision at a each moment in time, but the cumulative effect of those decisions is not one they would have chosen. Spending decisions have been taken incrementally, with political and policy pressures exerting themselves at each point. Three year cash spending plans are a sensible idea in most circumstances, and were indeed thought to be a major step forward over annual settlements. But they produce unplanned expansions in real spending if stuck to in a deflationary recession. If subsequently a government feels politically obliged to commit to protect these areas, irrespective of how well they have fared relative to other areas (as arguably the new Coalition government did with the ringfences on health, aid and commitments to pensioners), we can end up with a radically different structure of public spending to anything which we would have consciously planned. This is because we never stand back and take a look at the cumulative impact of individual decisions and ask whether that is the outcome we want. If we are now back in the world of “boom and bust", we need to think hard about how our public finance frameworks (and associated political debates) operate in a world of large cyclical swings. After all, who knows when we might go through this all again.

- Keywords

- Budget Spending review Economy Austerity

- Administration

- Cameron-Clegg coalition government

- Publisher

- Institute for Government