Five things we learnt from the 2020 spending review

Before the spending review, we outlined five things to look for in the chancellor’s announcement. We assess what the statement told us about each one.

On Wednesday 25 November, Rishi Sunak announced the outcome of the spending review – laying out how much money departments will have to spend next year. Alongside that, he presented the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR’s) latest forecasts for the economy and public finances.

While the chancellor has made more policy statements this year than some chancellors do in an entire career, this was the most important since his budget speech in March.

He announced record borrowing and public spending forecasts, as well as big changes to the outlook for the economy since the last forecast in March. Despite there being a vaccine on the way, the economic and public finance consequences of the crisis will continue to be felt long after we stop social distancing.

The spending review set the budgets for day-to-day spending by departments next year, as well as outlining capital spending plans for the next four years. There was extra money for public services to deal with coronavirus next year, but also some signs of spending restraint, notably cuts to the aid budget and public sector pay.

Before the spending review, we outlined five things to look out for in the chancellor’s announcement. We have now provided our analysis on what the statement told us about each of these.

1. How will economic performance depend on the path of the virus?

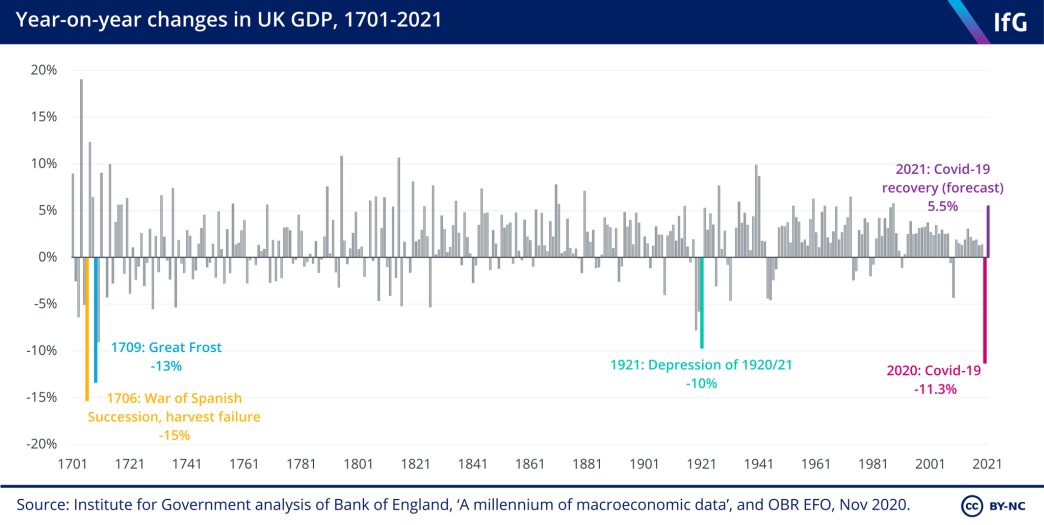

The OBR’s forecast today confirmed what we already expected: the economy will contract sharply in 2020, shrinking more than it has in any year since 1709 (see figure below). The better news is that this is as bad as the OBR thinks it will get. In 2021 and 2022, the economy is expected to grow quickly – by 5.5% and 6.6% respectively in the central forecast. This scenario assumes that a vaccine will be rolled out next year, meaning we can release restrictions in mid-2021.

However, even with this accelerated growth, the economy is only expected to recover to pre-Covid levels at the end of 2022 – and will remain 3% smaller even in 2025 than it would otherwise have been had coronavirus not struck. That means that the virus will have done permanent economic damage even if our lives can get back to normal once a vaccine is rolled out.

In the short term, there may still be some more economic pain to come even as growth picks up. Unemployment is expected to reach 7.5% in the second quarter of 2021 in the central forecast, much higher than the current 5% and only a little below the financial crisis peak of 8.4%. That explains why the chancellor focused so much on a plan for jobs, which he will hope can reduce unemployment more quickly than the OBR’s forecast; it expects unemployment to remain above 5% until the end of 2023.

2. How generous are the government’s spending plans for next year?

This year, departments are set to spend unprecedented amounts, with day-to-day spending on public services at almost £500bn, compared to a planned £350bn. Spending is expected to remain elevated next year, with the Treasury earmarking a further £55bn for coronavirus-related spending. The NHS is the main recipient of this additional spending, and it could easily turn out to be much higher or much lower depending on the path of the virus.

However, even amidst the excess, there are signs of the Treasury attempting to impose restraint. ‘Core’ (i.e. non-coronavirus-related) day-to-day spending will be around £10bn lower next year than originally planned in March. The biggest loser from this is the overseas aid budget, cut to 0.5% of national income, while the partial public sector pay freeze also reduces government spending.

The government is currently assuming that any coronavirus-related spending will be confined to this year and next. Beyond that, the plan is to limit growth in core day-to-day spending to 2.1% a year in real terms. But generous multiyear spending settlements for some of the biggest areas of spending – including the NHS, schools and defence – mean much of that budget has already been allocated. That leaves the rest facing spending growth of around 1½% a year. For some departments, that could quickly be swallowed up if some of the extra costs this year prove to be more persistent

The story on capital spending is quite different. The government has stuck to the plans set out in March for departments’ capital spending, which means that net investment is set to reach almost 3% of GDP next year and stay around that level for the next few years.

3. Are there credible plans and resources to address backlogs in badly affected public services?

The government has allocated public services a lot of additional funding to respond to coronavirus. The chancellor plans to spend £124bn more than expected in the March budget this year, and an extra £55bn next year – with £21bn of the latter yet to be allocated.

Beyond Covid-19, the multi-year spending settlements for the NHS, schools and defence will eat up more than half of day-to-day spending, meaning that spending for other unprotected areas will be tight. Indeed, the government plans£10bn less for day-to-day spending next year than outlined in the 2020 budget.

Looking at individual services, the government announced that it would allow local authorities to access an additional £1bn for adult and children’s social care – which were particularly badly hit by the pandemic. However, £700m of that will be raised by increasing council tax. Whether this will be enough to maintain standards in adult social care depends on whether the rest of the local government settlement is enough to respond to coronavirus pressures.

In addition to the multi-year settlement that had already been announced, schools will be given £1.8bn over this year and next to pay for free school meals and to help pupils catch up on learning missed while schools were closed during the first wave of the pandemic. This should help but the money is not targeted specifically at disadvantaged pupils who are the most likely to have missed out while schools were closed.

The spending review also contained some funding earmarked to address backlogs that have built up this year because of coronavirus. The NHS has been given £1bn to reduce the backlog of elective surgeries and the justice system will get £337m to address the impact of Covid-19 and the consequences of hiring additional police officers.

This money will go some way to reducing the backlogs we documented in our recent Performance Tracker analysis, published in partnership with CIPFA. To understand exactly how much difference it will make to the backlog in the criminal courts, we need further details on the number of extra sitting days that will be funded and how many cases can be processed while social distancing rules remain in place. In the NHS, the funding will not be enough to clear the backlog quickly, meaning patients are likely to wait longer than they did pre-crisis for years to come. Given NHS staffing shortages at the start of the pandemic and the time it takes to recruit new staff, the main challenge will be ensuring that the NHS has enough staff to increase activity.

4. Will investment plans be re-focused towards ‘levelling up’ and net zero?

This was a spending review that followed through on the government’s commitment to boost investment, gave clear signals about the government’s priority to “level up” and rewrote rules for how projects will be selected – though those hoping it would be the moment that the Treasury “turned green” were disappointed.

The chancellor set out what he described as the highest level of public investment in 40 years, with funding for roads, rail, broadband, flood defences and green energy. The long-awaited National Infrastructure Strategy brings these plans together, with the aim of providing additional certainty to departments and their supply chains.

The government has so far been vague about what “levelling up” means, but Rishi Sunak announced a £4bn fund through which local authorities will be able get money for projects such as improving high streets. These will need to be completed in the current parliament, meaning it will favour “shovel-ready” projects and local authorities good at writing bids.

On net zero, the chancellor did not add much to what was in the prime minister’s 10-point plan last week, while some announcements (such as on roads) will add to emissions. Funding on energy efficiency remained less than the government’s manifesto commitment, with other decisions again delayed. Overall, planned investment is still some way short of what the Climate Change Committee thinks is required to get the UK on track for reaching net zero by 2050.

Two further big announcements were not investments – but changes to how projects will be chosen and financed. The Treasury published a review of the Green Book appraisal process, which puts greater emphasis on whether projects meet policy objectives than if they have a good benefit-cost ratio. What difference this makes in practice remains to be seen.

Rishi Sunak also announced the creation of a new Infrastructure Bank to “catalyse private investment”, partially filling a gap left by George Osborne’s decision to sell off the Green Investment Bank – and the imminent loss of access to the European Investment Bank. The big questions are the scale and remit of this new body – with answers not due until the 2021 budget.

5. How big is the medium-term hole in the public finances?

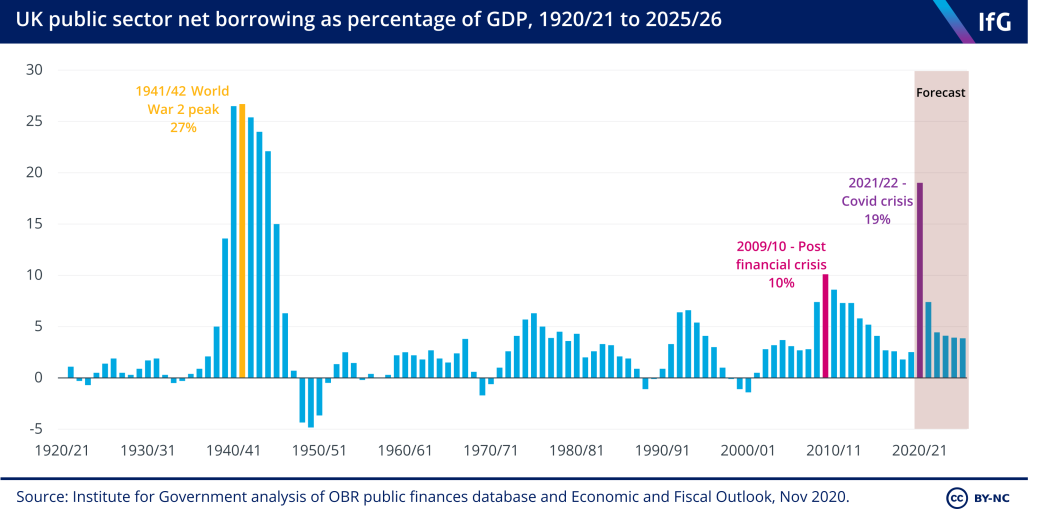

The new OBR estimates of what borrowing will be this year and next (£394bn and £164bn respectively) are staggering by any normal standards. Just eight months ago, the OBR predicted that the government would borrow only £55bn this year and £67bn next.

But more worrying for the chancellor is what today’s OBR forecasts say about borrowing in the medium-term – that is, once the Covid shock has passed and the economy has recovered. On that front, the new forecasts make for even grimmer reading. The OBR now estimates that the UK economy will take a permanent hit from the pandemic – leaving it 3% smaller than was previously expected, even in five years’ time. Borrowing in turn is expected to remain elevated – at 3.9% of GDP in 2025/26. This would be substantially higher than forecast back in March. Since the second world war, the UK has only had borrowing at that sort of level during recessions and their immediate aftermaths.

As Rishi Sunak acknowledged in his speech, the UK could not sustain borrowing at this level for long. He said very little about how he plans to fill this hole in the public finances. For now, the economic and public health imperative is for the chancellor to keep spending. But at some point before the next election, he and the prime minister will have to start laying out what tax rises or spending cuts will be needed to fill this hole and "return to a sustainable fiscal position", as Sunak said on Wednesday is his objective. If the government wants to borrow only for investment (as the fiscal rules set out in the Conservative manifesto would require), the chancellor will need to find net tax rises or spending cuts worth around £25bn a year. More likely £40bn would be needed if he wanted to restore the headroom against this target that he had back in March.

- Position

- Chancellor of the exchequer

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Department

- HM Treasury

- Public figures

- Rishi Sunak

- Publisher

- Institute for Government