Rebuilding trust in public life

The next government should start the difficult process of showing the British public that the institutions on which we all rely can be trusted.

Introduction

Trust in the institutions of public life has taken a beating after years of scandal in UK politics. From MPs’ lobbying to corruption allegations concerning the government’s response to the pandemic – and, of course, the ‘partygate’ affair that implicated figures at the very heart of government during that crisis.

As Ipsos polling commissioned specially for this report shows, there is a sense among the public that people in power do not feel bound by the same rules as them. Two thirds of respondents said that they do not think the current government behaves according to high ethical standards (65%); approaching half believed standards of behaviour had got worse since the 2019 general election (45%).

The general election that will take place this year offers both the main parties a chance to reset these perceptions. They should take it. But this needn’t wait till the morning after the vote: both can set out from now how they plan to fix the situation should they enter No.10.

Over the past half-decade, and particularly (though not exclusively) during the premiership of Boris Johnson, UK government has been beset by a torrent of scandals in which the ethics and judgment of senior ministers and their closest teams have been found severely wanting. Johnson was himself the focus of many of these, from his use of a Conservative donor’s funding to refurbish the Downing Street flat, to the parties held in it and No.10 while the rest of the country was in lockdown, and finally to his support for Chris Pincher, the former deputy chief whip accused of sexual harassment – the event that proved the final straw for Johnson’s MPs, who ultimately prompted Johnson’s resignation and a leadership contest and in July 2022.

Another former prime minister also made the headlines in this period, in this case for their behaviour after leaving office. David Cameron was found to have repeatedly lobbied government figures, including the then chancellor Rishi Sunak, on behalf of a since-collapsed finance firm, Greensill Capital, whom he was employed by two years after leaving office. No rules were technically broken, but the Treasury Select Committee issued a scathing report on the affair in 2021, criticising the former prime minister’s “significant lack of judgment”. David, now Lord, Cameron was made foreign secretary by Rishi Sunak in 2023.

Despite entering No.10 amid promises of integrity, Sunak too has found himself at the head of a government marred by ministerial scandals. Among other examples, his party chair, Nadhim Zahawi, and deputy prime minister, Dominic Raab, were both forced to step down in the first year of Sunak’s premiership due to tax irregularities and bullying respectively (though Sunak took a different approach to his predecessor but one in not fighting to keep these ministers in his government).

The context – and result – of this era of scandal in politics

This period of regular scandals is one in which the UK has faced sustained constitutional and political instability – with the Brexit vote, frequent changes of prime minister and myriad other crises undermining the UK’s reputation at home and abroad. In the 2023 Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index, the UK had fallen to 20th in the world, down from 18th a year before, and 11th in 2021, with Transparency International noting last year that the UK had seen “a string of political ‘sleaze’ and public spending scandals”. 34 Transparency International, ‘9 countries to watch on the 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index’, blog, 14 February 2023, www.transparency.org/en/blog/cpi-2022-corruption-watch-list-united-kingdom-sri-lanka-georgia-ukraine

The result is the UK public losing faith in politicians. There is a widespread sense that people in positions of power do not believe the usual rules apply to them, or that UK government more generally is not working for the benefit of the public. The Ipsos Veracity Index 2023 found that as little as 10% of the public trusts government ministers to tell the truth, and only 9% trust politicians in general to do the same. Polling commissioned by Spotlight on Corruption found that 71% of people do not trust politicians to police the rules governing their own behaviour.

Institute for Government/Ipsos polling, February 2024

The IfG commissioned Ipsos to carry out some polling when researching this report.* This was done over the weekend of 16–19 February 2024, and the key findings are found below:

- 65% – do not think the current government behaves to high ethical standards

- 45% – think standards of behaviour in government have got worse

since the election in 2019 - 53% – of 2019 Conservative voters would not trust a Conservative government after the next election to behave to high ethical standards (among all adults, 65% do not have much trust)

- 19% – of 2019 Labour voters would not trust a Labour government after the next election to behave to high ethical standards (among all adults, 44% do not have much trust that they would behave ethically)

- 26% – would change their vote if the candidate of their preferred party was found to have broken ethical standards of behaviour.

* Ipsos interviewed a representative quota sample of 1,079 adults aged 18-75 in Great Britain. Interviews took place on the online Omnibus 16-19 February 2024. Data has been weighted to the known offline population proportions. All polls are subject to a wide range of potential sources of error. A full table of results can be found at the bottom of this page.

In this context, the upcoming election is an important opportunity for both the main political parties to make meaningful, concrete promises that they will do things differently if elected. This would not be without precedent: in the 1990s Labour committed to introduce Freedom of Information legislation after 1997; last year the party used an IfG keynote speech to announce its plans for a new ethics committee. David Cameron set out core transparency commitments ahead of the 2010 election.

Whatever the result of the election, the next government should take this opportunity to show that it will do things differently from recent administrations. This means strengthening the rules that govern how people in government behave, ensuring that the relevant regulator(s) are able to enforce those rules properly, and being open and transparent about what is happening in government.

The general election that will take place this year offers both the main parties a chance to reset public perception that people in power do not feel bound by the same rules as them.

The need to rebuild standards in public life

Cleaning up public life is an end in its own right, but it is also an important means to other ends. By showing that it cares about integrity and professionalism, the next government will be able to start rebuilding trust in public institutions and create breathing space for it to focus on its own priorities, rather than having to constantly defend ministers accused of wrongdoing or deal with criticism over its approach to ethical questions.

This breathing space will prove useful. It will grant the new administration more capacity to focus on a much-needed and oft-cited growth agenda, recently frustrated by the political instability of recent governments. 36 Partington R, ‘UK’s political short-termism is killing hopes of business investment’, The Guardian, 24 September 2023, www.theguardian.com/business/2023/sep/24/uk-political-short-termism-killing-hopes-business-investment By showing it is serious about ethical government, the next administration will also be able to attract good quality people to apply for leadership positions across the public sector. This would require reversing the impression that public appointments are a foregone conclusion (as many felt was the case during the long-running attempts by the Johnson government to install its choice, Paul Dacre, as chair of Ofcom) and treating candidates better throughout the process.

Of course, building back the UK’s reputation for ethical government will be an ongoing process rather than something that can simply be fixed in an instant – but the incoming government after the election has an opportunity to kick-start a process of change.

The Conservative Party has not said anything on this issue yet, though the Sunak government set out a series of proposals in July 2023 for greater transparency around ministers’ meetings and to improve the enforcement of the rules around ministers’ post- government jobs. These commitments are sensible – and any government should see them through – but ministers have rejected many other suggestions from the Committee on Standards in Public Life (CSPL), meaning there is still much more to be done.

The Liberal Democrats passed a motion at their 2023 party conference calling on the government to take various steps to improve ethics in public life, many of which align with recommendations from the CSPL. Labour, for its part, has said that it will establish an Integrity and Ethics Commission to strengthen standards in government and ensure they are properly enforced. Given that a quarter (26%) of respondents to our poll said that they would change their vote if their preferred candidate was found to have broken ethical standards, it is in all parties’ interests to fix this system.

This paper offers the IfG’s recommendations for how the next government, whoever wins the election, can make substantial – and quick – progress on this important topic. All of the suggestions here would be compatible with Labour’s proposed commission. However, importantly, many can be taken forward before any such commission is established, ensuring there is an ongoing improvement in standards rather than things standing still while the new body is set up.

All political parties should commit to cleaning up politics to restore trust in government, parliament and public bodies. To do so, there is no substitute for clear leadership – the next prime minister must make a priority of setting clear rules and committing to upholding them.

How to rebuild trust in public life

With scandal surrounding government for half a decade, fully rebuilding trust in public life will take time. But there are quick changes that the next government can make early in the next parliament to start fixing the problem – our ‘Quick wins’, below. We then go on to look at what that same government could do in the medium and long term to more concretely improve how ethical standards and propriety are upheld in government, and thereby work towards rebuilding trust in our democratic institutions.

Quick wins

There are some things the next prime minister can do soon after the next election (and indeed that Rishi Sunak could do now) that would kick-start an improvement in how ethical standards are upheld in government. The current government has committed to several steps following the CSPL, Boardman and PACAC reports published in 2023 (outlined in detail in our explainer on the topic). These should be implemented. But there is much more that can be done. After the election, the prime minister should:

1. Issue a new ministerial code, with a clearer division between ethics and day-to-day bureaucratic processes

The next government should publish a new ministerial code in its first month in office. The code currently includes both procedural government guidance about practical matters like the ‘write-round’ process for collective decision making across government alongside rules about ministers’ conduct. These are closely related, but a clearer distinction between the two sets of requirements would make it clearer for ministers – and the public – to understand what is expected of them.

As with the present code, it should outline the types of misconduct breaches and the range of sanctions they may attract. The code should also be updated to reflect government’s working practices in the 2020s – including guidance on relationships in government and the use of personal phones and social media.

2. Give the prime minister’s independent adviser full investigative powers

Alongside the new code, the prime minister should give the independent adviser on ministers’ interests, currently Sir Laurie Magnus, the ability to initiate their own investigations and publish the findings (should Labour enter government this role is likely to be taken inside its ethics commission).

Boris Johnson actually took a step in this direction when his government allowed the independent adviser to start his own investigations – though having first sought permission from the prime minister. 41 Cabinet Office, ‘Revisions to the Ministerial Code and the role of the Independent Adviser on Ministers’ Interests’, GOV.UK, May 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/revisions-to-the-ministerial-code-and-the-role-of-the-independent-adviser-on-ministers-interests Giving the independent adviser, or the independent commission, this power, and the power to publish his findings independently, would show that the government is serious about proper enforcement of the ministerial code while still allowing the prime minister to make the ultimate, political decision about what sanction any minister found to have broken the code should face.

The adviser – or commission – should also be allowed to set out when they do not think they should investigate allegations of misconduct, because they do not meet the relevant threshold. The prime minister should commit to appointing a future independent adviser by open competition, rather than by choosing them personally.

3. Require ministers to sign a legal deed of undertaking on their post-government jobs

The question of how to enforce the rules that ministers face once they leave government has been particularly vexed in recent years – Boris Johnson failed to check whether his role as a columnist for the Daily Mail was in breach of the rules, 42 4 Advisory Committee on Business Appointments, ‘Correspondence from ACOBA to Boris Johnson, breach of the Rules (Daily Mail)’, GOV.UK, updated 27 October 2023, www.gov.uk/government/publications/johnson-boris-secretary-of-state-foreign-and-commonwealth-office-acoba/correspondence-from-acoba-to-boris-johnson-… and Matt Hancock also failed to do so before his reality television appearances. 43 Advisory Committee on Business Appointments, ‘Correspondence between ACOBA and Matthew Hancock regarding two television series – ITV’s ‘I’m a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here’ and Channel 4’s ‘SAS Who Dares Wins’, GOV.UK, updated 21 December 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/hancock-matt-secretary-of-state-department-of-health-and-social-care-acoba-advice/correspondence-between-acoba-and… Both went ahead with the roles and were found (retrospectively) to be in breach of the rules that would have been imposed by the Advisory Committee on Business Appointments (ACOBA) – they faced no meaningful consequences.

In July, the government said that it would require ministers to sign a legal “deed of undertaking” that they would abide by the rules as advised by ACOBA, but no such deeds have yet been introduced. 44 Burghart A, ‘Ministers: Advisory Committee on Business Appointments’, answer to written question for Cabinet Office, UIN 1852, 22 November 2023, https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2023-11-14/1852 When the prime minister makes ministerial appointments after the election, they should require all ministers to sign such a deed immediately, as a condition of their appointment.

4. Establish a constitutional centre of expertise under the cabinet secretary

The UK constitution has been strained in recent years. However, responsibility for the constitution in the UK government is unhelpfully diffuse, being split between the Ministry of Justice, the Cabinet Office and the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. This disperses constitutional expertise across government and makes it harder for the civil service to have a long-term view on the constitution, precedent and norms that is independent from the government of the day.

The prime minister should establish a central unit that brings together all the relevant advisory functions to build institutional memory, support the cabinet secretary in their constitutional advice, and provide expert and in-depth knowledge to ministers. This unit would not take over policy responsibility from other departments – the relationship with the judiciary will always be held by the Lord Chancellor and the Ministry of Justice, for example – but it would act as a permanent hub for constitutional expertise in the civil service.

While a prime minister can easily establish new structures and roles shortly after an election, the most important thing for the government is to establish a culture of integrity and adherence to expected standards of behaviour. The leader of the winning party should ensure that his ministerial team are committed to high standards: one option would be to require cabinet appointments to publicly commit to upholding the ministerial code, in the form of a signed, published letter perhaps, which would serve to remind them and the public that this is a key responsibility of their role.

The next prime minister should build on the current government's commitments to report other forms of contact where government business is discussed, including WhatsApp conversations.

Structural changes

Beyond the immediate changes that any prime minister could put into effect now or straight after the next election, there are other improvements that will take more time to set up but that will help the new government rebuild trust and faith in public institutions over the medium term.

1. Improve quality and regularity of departmental transparency publications

Current information on who ministers and their special advisers meet, what they discuss and what hospitality they receive is of patchy quality and often published late (though performance has improved in recent months). The prime minister after the election should build on the current government’s commitments, also from July 2023, which included a single platform or ‘dashboard’ collating this data by publishing information on a monthly basis, ultimately moving to a fortnightly basis to bring government in line with MPs; and reporting other forms of contact where government business is discussed, such as informal meetings, substantive email exchanges, phone calls, text messages and WhatsApp conversations.

The current government has committed to extending the transparency requirements to more of the senior civil service, but the next government – whether Labour or Conservative – should go further and include special advisers in all the publications too. 47 Burghart A, ‘Government Transparency and Accountability’, statement UIN HCWS138, 14 December 2023, https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-statements/detail/2023-12-14/hcws138 The prime minister should hold departmental secretaries of state and permanent secretaries accountable for the quality, accessibility and reliability of their department’s transparency returns, while departmental select committees should also scrutinise the timeliness of returns.

2. Improve data on, and transparency of, the public appointments process

Currently the appointments process is affected by frequent delays, which both put good candidates off applying and result in gaps in key roles while appointments are in progress. The government needs better and more transparent data to help resolve these delays. While recent improvements have made the public appointments website more accessible and introduced more comprehensive coverage of recruitment campaigns, the information government publishes on when decisions are made and who panellists are remains patchy.

The prime minister after the election should ensure that all of this information is consistently available in a timely way, as well as publishing data on how long each stage of the appointment process takes (as already happens in Scotland). 48 Ethical Standards Commissioner, Public Appointments Annual Report 2021/22, 31 October 2022, pp. 19–21, www.ethicalstandards.org.uk/publication/public-appointments-annual-report-202122 They should not be afraid to act on what the data shows: whether delays are caused by ministerial private offices, departmental processes or the centre of Whitehall, reducing them would improve public sector leadership as well as making more efficient use of ministers’ time. These changes should be made in addition to regularly publishing a list of unregulated appointments, as the current government has already committed to do.

3. Enforce the rules on post-government roles

The current government has already committed to changing civil servants’ contracts and requiring ministers to sign a deed of undertaking about their post-government work, but it will be for the next government to ensure that these changes come into effect and are properly abided by. If Labour wins, it may be particularly keen to ensure that former Conservative ministers stick to the rules, but it will also need to show that it is enforcing them against its own ministers who leave government in the future.

The party has suggested that its new Integrity and Ethics Commission will have the power to levy fines against former ministers found to have broken the rules; before that organisation is established, however, it will be for ACOBA, departments and the prime minister to ensure that the agreements ministers and officials sign are properly enforced. The next government should monitor compliance with the rules and, as the current government committed to in July 2023, consider taking further powers to “explore further sanctions, such as financial penalties” where individuals have not complied with the rules. 52 Cabinet Office, Strengthening Ethics and Integrity in Central Government, CP 900, The Stationery Office, July 2023, p. 9, www.gov.uk/government/publications/strengthening-ethics-and-integrity-in-central-government

4. Strengthen routes for whistle-blowing in the civil service

The partygate scandal, Dominic Raab’s resignation and the Foreign Office’s chaotic evacuation of Kabul highlighted that there needs to be clearer routes for whistle- blowing in the civil service. Sue Gray, the former second permanent secretary at the Cabinet Office, now chief of staff to Sir Keir Starmer, found in her investigation into partygate that officials felt unable to highlight where they felt misconduct was taking place and recommended that “there should be easier ways for staff to raise such concerns informally”.

The government rejected this recommendation, and a similar proposal in the Boardman report that it strengthen whistle-blowing processes for civil servants, saying: “Civil Service HR undertakes continuous improvement of whistle-blowing processes.” 53 Cabinet Office, Strengthening Ethics and Integrity in Central Government, CP 900, The Stationery Office, July 2023, p. 9, www.gov.uk/government/publications/strengthening-ethics-and-integrity-in-central-government The next prime minister should require permanent secretaries to ensure that they have robust, trustworthy routes for staff to raise concerns about departmental performance and the behaviour of ministers, and to reassure officials that complaints will be properly investigated. 54 Thomas A, ‘Raab’s resignation should lead to reform of the complaints process against ministers’, blog, Institute for Government, 21 April 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/raab-resignation-complaints-process

All of these changes will require sustained leadership from ministers and senior officials in departments – it will not be enough to say that things are going to change, departmental leaders will have to show that they are making real change. To take bullying as an example, where ministers are known to be behaving poorly towards their colleagues, senior officials need to raise this. Some form of training on appropriate behaviour in government may be of benefit – to ensure that it is taken up by the people who will benefit most, the prime minister will have to set out a clear expectation.

High ambition: legislation

All the changes we have identified so far could be made now or in the first few weeks of a new parliament, or at least set in motion at that point. But if the incoming prime minister wanted to go further, and really protect the independence of the standards and ethics system in government, they should introduce legislation to make these changes permanent and further strengthen the ethics regime in government. While there is always competition for legislative time in parliament, this bill could be relatively focused and straightforward – particularly if it was introduced after the more immediate changes we have suggested above. Lord Anderson has already introduced just such a bill to the House of Lords, to implement many of the CSPL’s recommendations. 60 House of Lords, Public Service (Integrity and Ethics) Bill [HL], Session 2023–24, last updated 19 December 2023, https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3552

1. Set out the powers of the independent adviser on ministers’ interests and require the prime minister to publish a new ministerial code

Unlike the codes of conduct for civil servants and special advisers, the ministerial code is not on a statutory footing and so a prime minister can abolish it at their discretion. New legislation should require the prime minister to publish a code governing the standards of behaviour, to make clear that ministers are just as accountable for their behaviour as the officials and special advisers that serve them, and to be clear that the prime minister cannot just abolish the code if they want. The legislation should not, however, specify the content of the code, as this would still be for the prime minister to decide.

As recommended by the CSPL and others, legislation should ensure that the ministerial code can be enforced by the independent adviser on ministers’ interests (or Labour’s independent commission). If Sunak is still prime minister after the election, he should ensure this bill sets out the powers of the independent adviser, including an ability to initiate his own investigations and publish the findings. If Starmer is in No.10, he should use this bill to set up the independent commission and set out its powers.

2. Put the appointments commissioner and governance code on a stronger statutory footing

The commissioner for public appointments regulates appointments to public bodies in line with the government’s governance code, but there are no formal ways of enforcing this code. Both the office and role of the commissioner could be changed or rescinded by ministers at any time, because they are set out in an order in council rather than in primary legislation. 61 The Public Appointments Order in Council 2023, 19 July 2023, https://publicappointmentscommissioner.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/2023-Public-Appointments-Order-In-Council.pdf The same is true of the governance code itself.

After the election the government should give the role a stronger statutory position and ensure that any major modification is agreed by parliament. This would give the commissioner more security and strengthen their ability to resist executive overreach in practice.

In line with recommendations made by the CSPL 62 Committee on Standards in Public Life, Upholding Standards in Public Life: Final report of the Standards Matter 2 review, November 2021, p. 14, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/617c02fae90e07198334652d/Upholding_Standards_in_Public_Life_-_Web_Accessible.pdf and PACAC, 63 House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, Propriety of Governance in Light of Greensill: Fourth Report of Session 2022–23 (HC 888), The Stationery Office, 2022, p. 21, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/31830/documents/178915/default the commissioner’s role should be put in primary legislation, stipulating that the commissioner is responsible for ensuring ministers comply with the governance code, in turn giving the code a strengthened statutory basis.

The legislation should also require the publication of the code of conduct for board members of public bodies – though, as with the ministerial code, it would not itself specify its content.

Labour’s Integrity and Ethics Commission may have a role to play in regulating public appointments as well as overseeing ministers and ex-ministers; at this stage it is not yet clear what the remit of that body will be. If it does extend to public appointments, the legislation should give it the powers described here.

3. Extend the lobbying register

David Cameron’s lobbying on behalf of Greensill Capital emerged a year after it took place because he was directly employed by Greensill, rather than contracted as a consultant. This meant he was not required to register his lobbying activity with the Office of the Registrar of Consultant Lobbyists. This made plain a gap in the governance that ultimately caused the government some embarrassment.

As recommended by the lobbying industry itself, 64 Chartered Institute of Public Relations, ‘New lobbying rules “fall short” of reform needed to restore trust, says CIPR’, 21 July 2023, https://newsroom.cipr.co.uk/new-lobbying-rules-fall-short-of-reform-needed-to-restore-trust-says-cipr the next prime minister should amend the Lobbying Act 2014 to include all lobbying of government, including that by in-house business lobbyists, incidental lobbying and lobbying of special advisers. The register should also cover other forms of contact aside from formal meetings, including phone calls and text messages. These changes would improve transparency around who exactly lobbies government – and how.

Parliament will play a key role in rebuilding public trust in the institutions and individuals of government.

A more assertive parliament

As well as the various actions that the government itself should take, parliament will play a key role in rebuilding public trust in the institutions and individuals of government. While the priority for the prime minister should be improving how government works, parliament for its part has a responsibility to hold government to account. A conscientious, strong government should want to support this wherever possible.

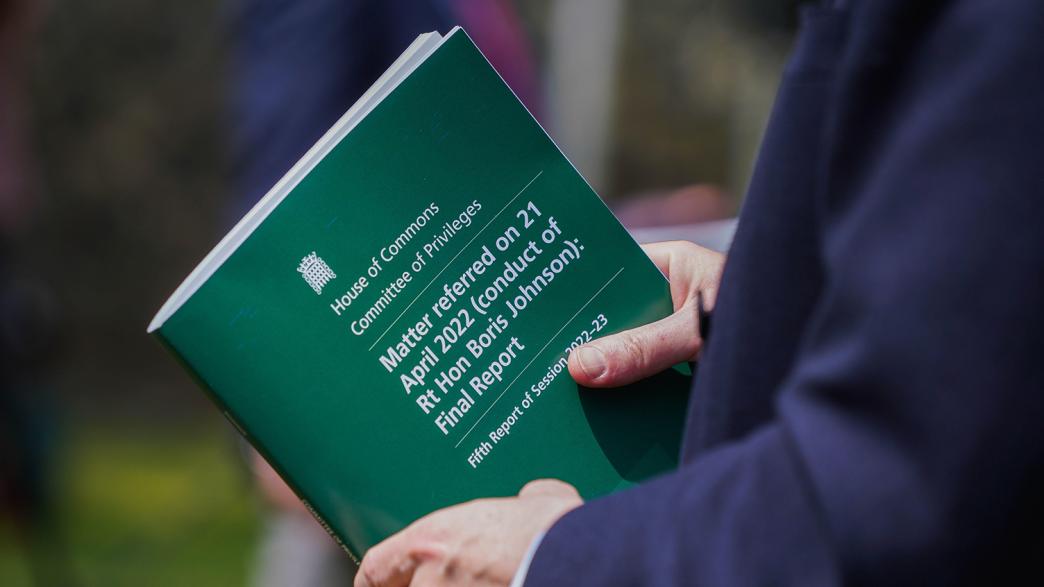

That is not to say that parliament has not played an important role in uncovering and tackling recent examples of poor behaviour. The House of Commons Standards Committee has been working to improve the Commons’ own processes for investigating failures of ethics and upholding standards, including how investigations work and what sanctions are available. This parliament has seen 10 MPs resign or be recalled because of misconduct. And, of course, the investigation by the Commons’ Privileges Committee played an important role in holding former prime minister Boris Johnson to account.

The next parliament should build on this approach. MPs should continue to take interest in how government is performing on ethics and transparency, as well as ensuring that parliament has a robust way of discussing constitutional issues and defending the constitution where necessary.

Conclusion

The question of ethical standards in government continues to matter to the public. And our polling shows it should matter to both the main political parties too: a clear majority of people (65%) believe the current government does not behave to high ethical standards, while a quarter (26%) would see an ethical scandal as a reason to change their choice of candidate.

Ahead of the election later this year, all the parties should commit to:

- Take concrete steps in the first weeks after the election to improve standards in government, including publishing a new ministerial code and giving the independent adviser the ability (but not the requirement) to investigate all allegations of ministerial misconduct, without requiring the permission of the prime minister.

- Improve performance on standards-related data and transparency across government – providing more regular updates, with proper detail – and create proper routes for whistle-blowing inside government.

- Legislate to put the ministerial code, as well as business appointments, conflict of interests and public appointments rules, on a stronger footing.

- Ensure that parliament continues to be able to hold ministers and senior officials to account for their behaviour, and that the government respects (and is seen to respect) the role of parliament in maintaining standards in public life.

All of these commitments are compatible with establishing an independent Integrity and Ethics Commission, as Labour has committed to do, but are also possible without such an institution. The next government should show that it has learned from the mistakes of recent administrations and, in turn, start the difficult process of showing the British public that the institutions on which we all rely can be trusted.

- Data document

- Rebuilding trust in public life - polling (VND.OPENXMLFORMATS-OFFICEDOCUMENT.SPREADSHEETML.SHEET, 68.74 KB)

- Topic

- Ministers

- Political party

- Conservative Labour

- Position

- Prime minister Secretary of state Minister of state Independent adviser on ministerial interests

- Administration

- Sunak government Johnson government

- Department

- Number 10

- Legislature

- House of Commons

- Public figures

- Rishi Sunak Keir Starmer

- Publisher

- Institute for Government