Performance Tracker 2022/23: Spring update - Summary

New funding was found for some public services at the autumn statement - but large challenges remain.

This is the second edition of Performance Tracker that the Institute for Government and CIPFA have published this financial year, in response to a fast-changing and crisis-driven period in public services and the new government’s decision to deliver a budget in March.

Since our October publication, we have a new prime minister – the third in a year – and widespread strikes have engulfed the country. Rishi Sunak’s government has made substantial changes to the spending plans set out in the 2021 spending review but the fragility of public services has remained and winter in the NHS has been as bad as feared. Despite the ‘twindemic’ of flu and Covid hitting hospitals and general practice as predicted, too little was done to prepare, in large part due to the political instability and administrative paralysis caused by the defenestration of two prime ministers over the summer and autumn.

These winter pressures have combined with long-standing problems in adult social care, hospitals and primary care and resulted in the worst NHS crisis in a generation. The elective waiting list stands at more than 7 million and bed occupancy is above 95%. Waits at A&E and for ambulances meaningfully improved in January, having reached record levels in December, but are still substantially worse than pre-pandemic. Failure in the health and care system are estimated to be contributing to hundreds of preventable deaths a week.

The situation in other services – while not quite as extreme – remains very concerning. Increasing numbers of recorded crimes go unsolved and a series of high-profile police scandals involving the Met and other forces have further damaged trust in the police and raised serious questions about the quality of leadership in the service. The case backlog in the crown court is at record levels and, when adjusting for complexity of cases, is more than twice as large as before the pandemic. The lack of progress in addressing court backlogs has meant that prisoner numbers are lower than the Ministry of Justice anticipated they would be. Despite this, some prisons still have insufficient capacity to safely offer even pre-pandemic standards of rehabilitative activity, and the government has been forced to make emergency use of 400 police cells.

In schools, the National Tutoring Programme is now reaching large numbers of pupils. However, evidence on its effectiveness is limited, and the overall pandemic catch-up programme is worth just a third of what the government’s own education recovery commissioner thought would be necessary to allow schools to make up for lost learning. Many children also continue to be let down by social care services, and the government’s response to an independent review has been criticised by the author of that review for being slow and lacking in ambition. -. The situation is particularly shocking for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children, hundreds of whom have gone missing from the Home Office’s care. 16 Fright M, ‘The government must urgently make clear who is responsible for children seeking asylum’, Institute for Government, 1 February 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/children-seeking-asylum

The Sunak government will need to grapple with these issues and more in the run-up to the next election. Public concern about health care is particularly high at the moment 17 YouGov, ‘The most important issues facing the country’, (no date), https://yougov.co.uk/topics/education/trackers/the-most-important-issues-facing-the-country and Sunak identified tackling NHS waiting lists as one of his top five priorities in a speech in January 2023. 18 Hoddinott S, The NHS crisis: Does the government have a plan?, Institute for Government, 26 January 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/nhs-crisis The analysis in this report outlines the scale of the challenge in nine public services – general practice, hospitals, adult social care, children’s social care, neighbourhood services, schools, police, criminal courts and prisons. To date, the new government’s decisions have done little to shift the dial and it will need to do much better if it wishes to campaign on its public services track record.

The autumn statement has eased some pressures, but services still do not have sufficient funding to return to pre-pandemic performance levels

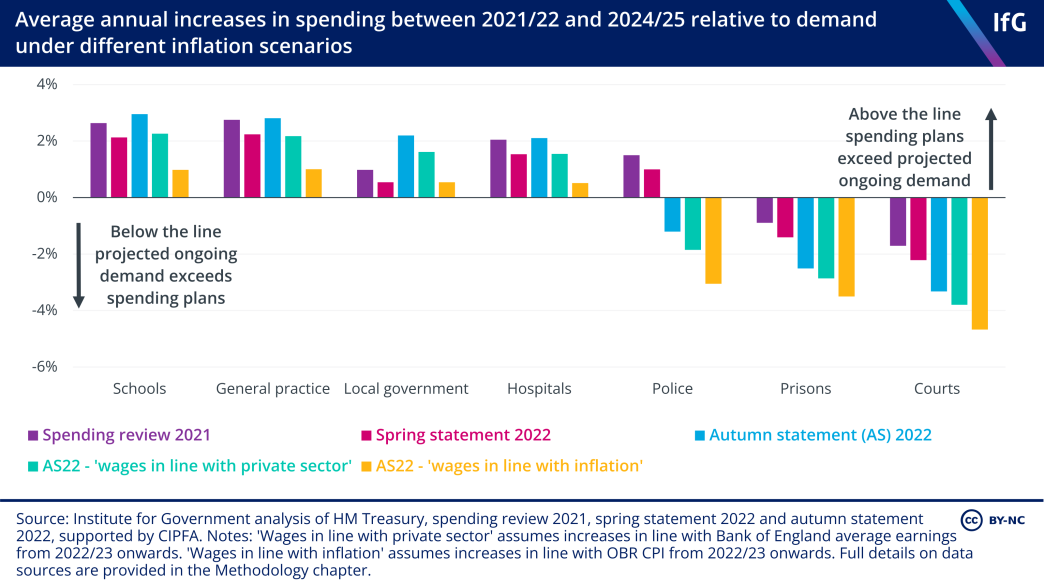

On 17 November, the government published an autumn statement. This was in effect a mini-spending review, making some substantial changes to public sector spending plans for the remaining two years of the current spending review period and beyond. As covered in detail in previous Institute for Government and CIPFA work 19 Davies N, Pope T, Nye P, Hoddinott S, Fright M and Richards G, What does the autumn statement mean for public services?, Institute for Government, 24 November 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/autumn-statement-2022-public-services , the overall settlement for day-to-day departmental spending across the current spending review period (2022/23 to 2024/25), was broadly as generous as when originally announced in October 2021, with additional cash in the autumn statement offsetting higher than anticipated inflation.

The NHS, adult social care and schools were the big winners from this, with each receiving meaningful funding increases. As a result, hospitals, general practice, schools and local government services should, assuming no change to productivity, now have enough money to meet inflationary pressures and ongoing demographic demand over the spending review period. However, it does not provide the level of funding required for major improvements to performance. First, because spending settlements are front-loaded, with big increases this year (2022/23) but little increase in the following two years. Despite this front-loading, the NHS in particular has not been able to convert additional funding and staff into increased activity, suggesting a fall in productivity. As such, in practice, the additional funding will not be enough to cover backdated inflation-level wage increases for 2022. Second, without further funding injections, an increased share of budgets will need to be spent on higher pay awards if they are used to bring strikes to an end. Third, performance in some services has got substantially worse over the last three years and reversing that will require considerable effort. As such, performance in these services is unlikely to return to pre-pandemic levels before the next election. This means that hospital waiting times and lists will remain above where they were in 2019, pupils will not catch up on lost learning, and the social care provider market will not be put on a sustainable long-term financial footing.

The situation in prisons and courts is arguably worse. With no additional funding announced in the autumn statement, progress in addressing the crown court backlog will be slow and the prison service will find it very difficult to safely house the expected increase in prisoner numbers.

Given the certainty of continued poor service-related performance and the prospect of ongoing industrial unrest across the public sector, it is unclear whether the government will find existing funding levels to be politically sustainable in the run-up to the next election. The situation will be even harder for whoever forms the next government. If the autumn statement’s spending plans for 2025/26 onwards were replicated at a spending review in 2025, it would be less generous than every spending review announcement since 2002 except 2010 and 2015, with the latter proving undeliverable due to poor performance.

The government’s strikes strategy has exacerbated existing staffing problems

Problems with the recruitment, retention and morale of staff are central to the poor performance of public services. The situation is particularly acute in adult social care, with 50,000 staff leaving the workforce in 2021/22. In the NHS, almost 10% of its roles were vacant at the end of September 2022: the worst gap on record. In schools, teacher training numbers are at crisis levels. There are fewer than three postgraduate trainee teachers for every five the government thinks are needed to staff secondary schools. And the situation is much worse for some subjects, with less than one physics trainee for every five required. In criminal courts, the deal to end the barristers’ strikes should prevent the situation from worsening, but there are still too few barristers to make much progress on the crown court backlog. Sickness and other absences have also remained high in many services, reducing staffing levels and increasing the pressure on other workers, who are already at heightened risk of burnout.

We warned in the autumn that substantially below-inflation pay offers would exacerbate these staffing problems. Since then, there have been widespread strikes across the public sector. Of the services covered in this report, schools and the NHS, particularly hospitals, have been worst affected. Members of the largest education union, the National Education Union, have begun strike action and two other teaching unions are planning to re-ballot their members after failing to meet turnout thresholds on a first attempt. In the NHS, nurses and ambulance workers have been striking since December and will be joined shortly on the picket lines by some junior doctors. More junior doctors may go on strike in March, depending on the results of a ballot by the British Medical Association.

Rather than seeking to quickly resolve these disputes, the government has refused to meaningfully discuss pay and introducing the Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Bill. This will allow ministers to set legally binding minimum service levels in health, education and other services, and enable employers to name which members of staff have to work to meet these service levels. In theory, the bill should make it cheaper for the government to resolve disputes, as it will limit the impact of strikes and therefore weaken the negotiating position of unions.

However, this strategy has and will continue to be damaging for the performance of public services and in many cases exacerbate the problems driving staffing crises. In the short term, it has extended the length and breadth of industrial disputes and the disruption caused. Strikes by nurses, junior doctors, ambulance staff and teachers could have been avoided had the government been more willing to discuss pay. It is notable that it was able to end strikes by criminal barristers by eventually offering an improved pay deal. In the medium term, the government’s actions have undermined trust in the pay review bodies. 20 Davies N, ‘The government’s strike strategy is damaging for public services’, Institute for Government, 17 January 2023, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/comment/government-strike-strategy-public-services With many unions now refusing to participate in this process, there is a greater likelihood that future pay decisions will also lead to strike action. In the long term, limiting the ability of staff to strike and paying them less than they think they are worth will exacerbate the already serious recruitment and retention problems facing public services.

There are no easy options for the government. Refusing to raise pay offers will make it much harder for the government to address backlogs and other public service performance issues. Raising pay but asking services to fund this from existing budgets will likely necessitate painful cuts as there is little meaningful fat to trim elsewhere. Similarly, increasing public service budgets to accommodate higher pay would require increasing taxes, higher borrowing or cuts to other public spending, none of which will be pain free.

Returning services to pre-pandemic performance levels, never mind those of 2010, is a daunting task. There is precedent for such an improvement, though: New Labour turned around a comparably bad NHS in the 2000s. But this required sustained investment, rather than short-term funding in responses to crises, and a strong focus on reform. Similar efforts are likely to be required now.

Return to Performance Tracker 2022/23: Spring update

Go to main page- Topic

- Public services

- Keywords

- Health NHS Social care Local government Schools Education Criminal justice Public spending Public sector Budget Spending review

- Department

- Department of Health and Social Care Department for Education Ministry of Justice HM Treasury

- Tracker

- Performance Tracker

- Publisher

- Institute for Government