Spending review 2021: what it means for public services

The spending envelope sets out the total amount of money the government plans to spend on departments and public services.

How big was the spending envelope?

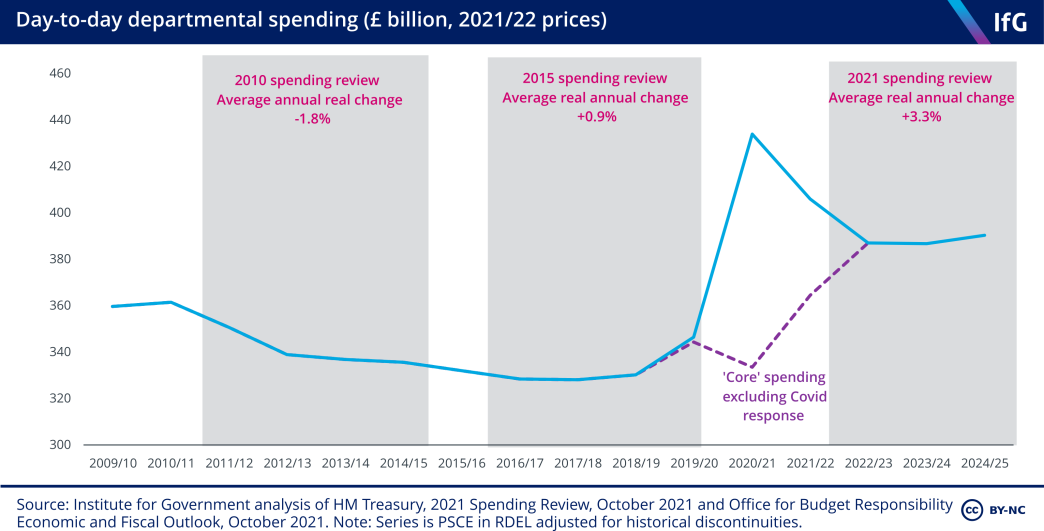

The spending envelope sets out the total amount of money the government plans to spend on departments and public services such as the NHS, schools, and local government over a multi-year period. The envelope for the 2021 spending review was much larger than the tight overall plans the Treasury was – supposedly – still committed to just a few weeks before the statement.[1]

The amount of money allocated for day-to-day departmental spending increases by 3.3% per year in real terms on average across the spending review period (which set budgets for 2022/23, 2023/24 and 2024/25). Notably, the increases are frontloaded. Excluding Covid-related spending, departmental budgets are set to grow by 10% in real terms in 2022/23 and then stay almost flat in real terms thereafter. This should allow departments to spend more to address Covid-related backlogs in the short-term.

How did the government allocate the money?

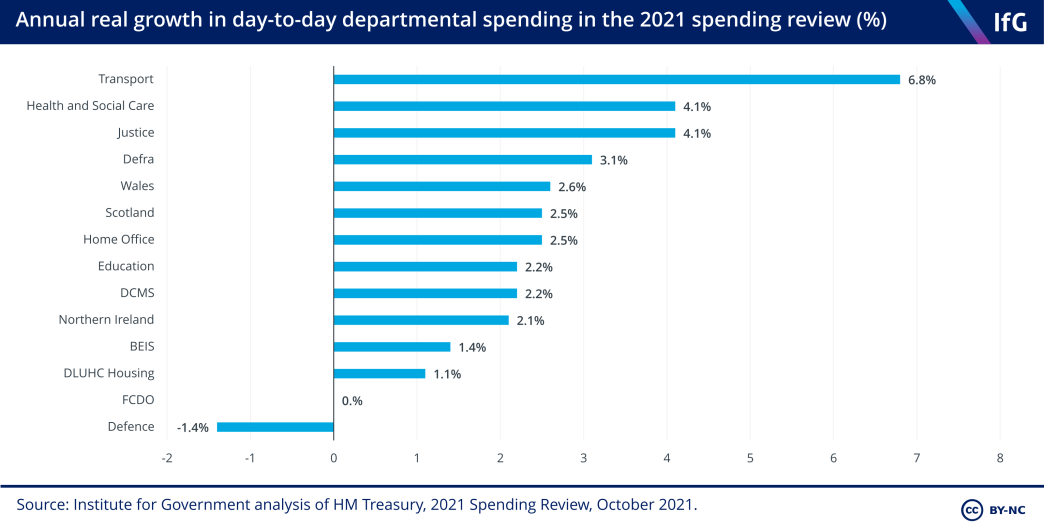

The large overall spending envelope allowed the government to be relatively generous across-the-board. Day-to-day spending on transport, health and justice will increase at over 4% per year in real terms. The increase for justice is especially notable given that real-terms cuts for that department have been pencilled in every multi-year spending review since 2004.

The only department that will see real-terms day-to-day cuts is defence (although its capital spending will increase). Other departments that might consider themselves a little hard done by are the Department for Education, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). They received below-average increases, although the FCDO budget will probably be boosted by as-yet unallocated aid spending in 2024/25 because the target will increase from spending 0.5% of gross national income on aid to 0.7% in that year if the government is meeting its fiscal rules.

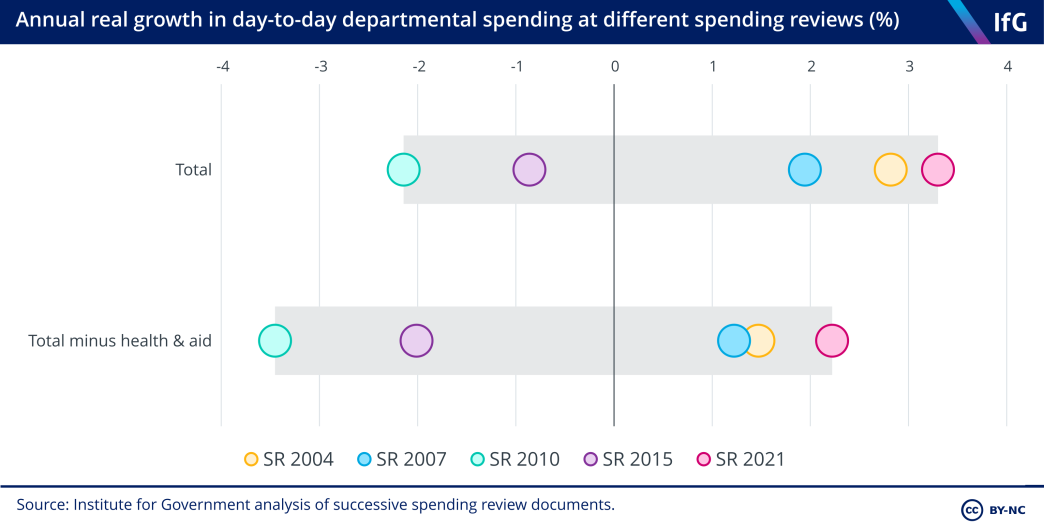

How does this compare to previous multi-year spending reviews?

Overall, this spending review is more generous than any of the multi-year spending reviews since 2004 for day-to-day spending. The health settlement was more generous than average, but the increases for day-to-day spending outside of health and aid (two regular ‘winners’ in past spending reviews) are also larger than those planned previously.

However, the context is important: the 2010 and 2015 spending reviews left budgets far below their 2010 level by 2020. In all but a few departments, increases in this spending review will only partially reverse those cuts.

For the nine public services we analyse in our annual data-driven report Performance Tracker, published in partnership with CIPFA, the spending allocations are generous when compared to how much public services spent in the 2010 and 2015 spending review periods.

Average annual change in spending during the 2010 and 2015 Spending Reviews, and 2021 Spending Review announcement implications[2]

Service |

Change in spending during spending review 2010 |

Change in spending during spending review 2015 |

Projected change in spending over spending review 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| General practice | 2.4%[3] | 5%[4] | NHS England: 3.8%[5] |

| Hospital | 1.6% | 2.7% | |

| Schools | 1.7%[6] | 0.4% | Schools: 2.2% |

| Adult social care | -2% | 1.6% | Local government spending power, excluding funding for social care reform: 1.9% |

| Children's services | -1.5% | 1.7% | |

| Local government services (excluding social care) | -4.8% | -1.5% | |

| Police | -3.1% | 0.9% | Home Office: 2.5% |

| Criminal courts | -5.6%[7] | 1.1% | Ministry of Justice 4.1% |

| Prisons | -3.8% | 3% |

Source: Institute for Government, Performance Tracker 2019; Institute for Government calculations using HM Treasury, Budget 2021, March 2021; Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and Fiscal Outlook, March 2021 and HM Government, Building Back Better: Our Plan for Health and Social Care, September 2021

Is it enough to maintain standards and address backlogs?

The government chose to increase day-to-day spending a lot over the rest of the parliament – with particularly large increases for the Department of Health and Social Care and the Ministry of Justice (MoJ). The chancellor repeated the government’s pledge of “world-class public services” four times during the budget speech[8] alone – but there were already rising demands for public services before the pandemic, and there will be additional costs required to catch up as a result of the pandemic.

We estimate that all the services we cover now have enough money to maintain standards – to allowing public services to maintain the quality and accessibility of services at pre-pandemic levels – although local authorities will continue to feel squeezed over the spending review. Spending on adult social care will have to increase faster than local authority spending power to provide care to the growing number of people eligible for the existing system. Adult social care will continue to eat up a larger share of local government spending over the rest of the parliament, even with the upcoming increases in council tax.

Addressing backlogs will be trickier. There is, in theory, enough money to address the elective care backlog in the NHS, as well as the backlog of cases waiting to be heard in the criminal courts. The real constraint will be whether the NHS can recruit enough staff to increase elective activity quickly and whether courts can find enough judges and barristers to work on criminal cases to clear backlogs quickly. In schools, however, the £4.9bn allocated to address lost learning is unlikely to be enough. It is substantially below our estimate of £13.2bn required to address lost learning, and below other independent estimates of between £13.5bn and £15bn.

General practice

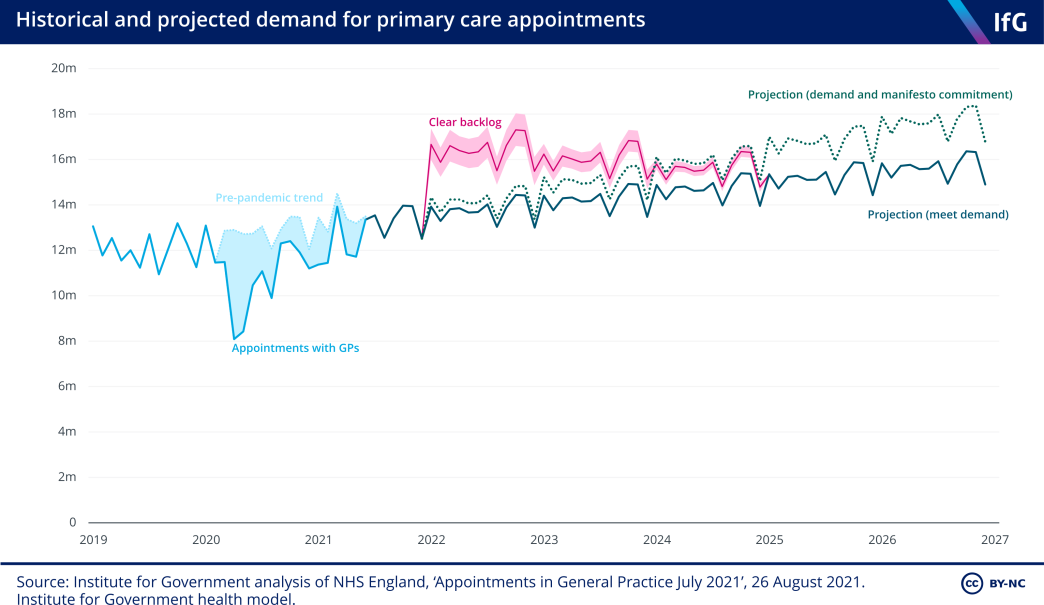

General practice was heavily disrupted by coronavirus, particularly during the first wave of the pandemic. The number of GP appointments fell by more than a third between the beginning of March and mid-April 2020 and there were over 6m fewer referrals from GPs to hospitals between March 2020 and July 2021. Primary care activity has since recovered and is at a level higher than before the pandemic, but general practice will need to offer a large number of appointments to find and refer missing patients to secondary care – whose treatment may be limited by hospitals’ ability to provide specialist care.

Using Health Foundation estimates[9], we project that underlying demand for primary care – excluding any Covid impacts – will increase 1.4% per year between 2019/20 and 2024/25, meaning that spending on general practice would have to be 7.2% higher in 2024/25 than in 2019/20 to provide care to the rising number of people in need of it. If spending on general practice rises in line with the total NHS England budget, which will be 16.5% higher in 2024/25 than in 2019/20, this should be enough to maintain standards.

Tackling the elective backlog by finding and referring people who have missed secondary care will be trickier. If GPs continue to refer patients to secondary care at the same rate as they did pre-pandemic and all of the missing referrals require secondary care and present at general practice over the next three years, then GPs would need to provide around 64.2m additional appointments to find and refer all these patients.

But general practice’s capacity to provide more appointments is limited by the availability of primary care staff. General practice is unlikely to unless there is a big near-term increase in general practitioners and primary care staff.

Hospitals

To respond to Covid and provide care for coronavirus patients, hospitals redeployed staff and reduced most non-Covid activity – which resulted in large backlogs of people waiting for routine operations. There were 5.72 million people waiting for elective care in August 2021, almost 30% higher than the 4.41 million people waiting in August 2019, the equivalent pre-pandemic month. Hospital outpatient activity and diagnostic tests returned closer to their pre-pandemic trends after March 2021, but most treatment areas are still performing fewer operations than their pre-pandemic trends and returning the backlog to pre-pandemic levels will take a sizeable increase in hospital activity.

Using Health Foundation estimates[10], we project that spending on acute care – outpatient, Accident & Emergency, elective and non-elective operations, excluding additional spending to reduce the Covid backlog – would have to increase 2.1% per year between 2019/20 and 2024/25 to provide care to the rising number of people in need of it. In other words, spending on hospitals would have to be 11% higher in 2024/25 than in 2019/20 to maintain standards. If spending on hospitals rises in line with the total NHS England budget, which will be 16.5% higher in 2024/25 than in 2019/20, this should be enough to maintain standards.

This leaves some money for the already-announced 3% NHS pay rise for most NHS staff[11] and money to tackle the backlog. Independent estimates of the one-off cost of tackling the Covid backlog vary from £6.5bn over three years[12] up to £15.7bn over four years[13], depending on how many ‘missing patients’ who did not seek care during the pandemic return, the cost of additional operations, and the hit to productivity as a result of ongoing infection control.

The government has provided £8bn to tackle the elective backlog over the spending review[14], which may be enough to eliminate the backlog on optimistic assumptions about the cost of operations and productivity – but in practice the main constraint will be the availability of skilled staff and facilities. The £2.3bn capital funding for diagnostic capacity such as MRI machines and £1.5bn for new surgical hubs and beds should help increase facilities and beds available for operations, but availability of staff will remain the key constraint. The Health Foundation estimate that eliminating the backlog over four years would require 800,000 more elective admissions above that required to meet demand, implying a large increase in doctors and nurses.[15] The government’s focus now needs to be on ensuring the NHS has the staff available to spend the extra money effectively.

Schools

Face-to-face teaching in schools ceased for all but the most vulnerable children and children of key workers during the first and third England-wide lockdowns. Schools provided remote learning while most children were unable to attend, but most children have missed just over 17 weeks of in-person schooling – equivalent to 44% of a school year – which is likely to have big long-term consequences. At the end of the spring 2021 term, primary school pupils were on average two months behind in reading and three months behind in maths.

The schools settlement agreed in 2019 will return per-pupil spending to 2010 levels by 2024/25[16] – more than enough to keep pace with the increasing number of pupils in schools and maintain standards. The government’s catch-up funding to address lost learning is much less generous, however. Including the £1.8bn announced in the spending review[17], the government plans to spend £4.9bn on education catch-up funding.

If pupils lost three to four months of learning as a result of the pandemic, we estimate that it would cost around £13.2bn to recover. The Education Policy Institute, an education think tank, estimates that £13.5bn would be needed[18], and Kevan Collins, the former schools recovery adviser, proposed a package of £15bn.[19] The government’s package is small relative to the scale of learning lost and is extremely unlikely to be enough to enable children to catch up on lost learning.

Local government services

Local authorities in England experienced a dramatic rise in costs while revenue from council tax, business rates, and charges all fell during the pandemic. The UK government covered these additional costs and lost income in aggregate during the 2020/21 year – but not for all local authorities. As a result, 46% of local authorities responsible for social care, and 72% of district councils, have had to use their reserves to cover Covid costs and avoid running a deficit. There are now backlogs in some local services – notably children’s social care, where there were 11% fewer referrals than the average of the same weeks between 2017 and 2020 and there may be a surge of referrals for children who needed but missed out on care during the pandemic.

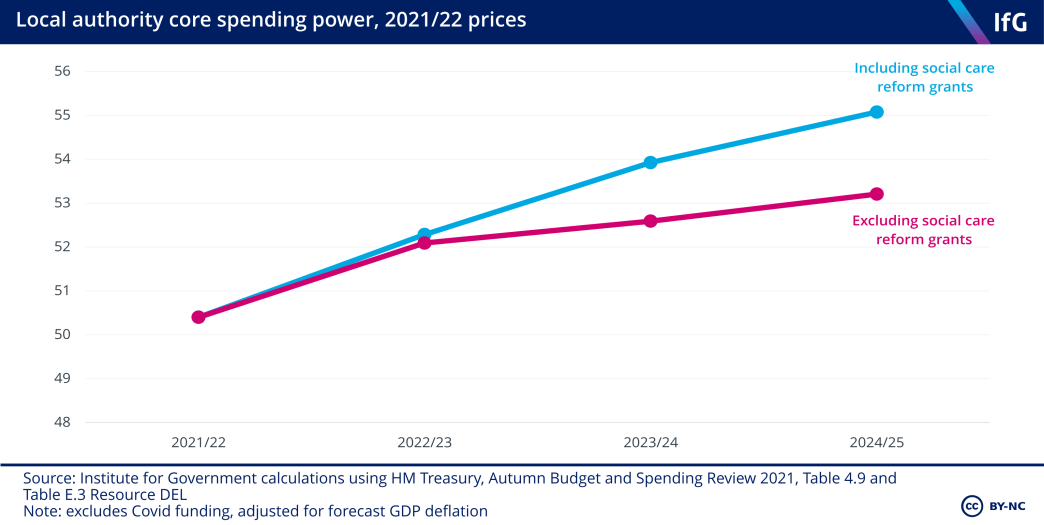

The government announced that local authority core spending power – the amount of money local authorities have to spend from government grants, council tax, and business rates – will rise 3% in real-terms each year over the spending review.[20] Local authority spending power will be 13% higher in real terms in 2024/25 than in 2019/20 as a result of increases in central grants and locally raised council tax and business rates.

Some additional central government grants are to implement the social care reforms – expanding access to means-tested social care and capping lifetime care costs – outlined in September 2021. Excluding these grants, local authority spending power is set to rise just below 1.9% in real terms each year over the spending review period and to be 9.1% higher in 2024/25 than in 2019/20.

This is below the 2.6% average annual real-terms increase between 2021/22 and 2024/25 which the Local Government Association had lobbied for[21], and just below than the 1.9% average annual real-terms increase between 2019/20 and 2024/25 which the Institute for Fiscal Studies thought local authorities needed to maintain service provision.[22]

We project that to maintain standards, local authorities would have to spend 9.7% more on adult social care, 4.8% more on children’s social care, and 2% more on other local government services in 2024/25 than in 2019/20. If care providers cannot absorb increases in the National Living Wage – which the government still intends to increase to two-thirds of median earnings[23] – and local authorities have to pay more for care, then local authorities would have to spend 19.6% more on adult social care in 2024/25 than they did in 2019/20. Including the cost of implementing the National Living Wage in adult social care, total local authority spending would have to be 8.8% higher in 2024/25 than in 2019/20 to maintain standards. Local authority spending power is set to be 9.1% higher in 2024/25 than in 2019/20. In aggregate, this will be enough to maintain standards, but rising demand for adult social care means that it will continue to eat up a larger share of local government spending over the rest of the parliament, continuing the trend of the last decade.

The majority of the increase in local authority spending power will come from locally-raised council taxes and business rates. The Office for Budget Responsibility projects that council tax receipts will be 10.8% higher in 2024/25 than in 2019/20[24], partly because of the government’s decision to allow local authorities to increase council tax by an additional 1% to pay for adult social care without holding a referendum (the adult social care precept)[6].

The increase in local authority spending power is unlikely to be enough to keep pace with rising demand for adult social care, meaning that local authorities will not be able to increase spending as quickly on other services – which have been cut sharply over the last decade. The decision to allow local authorities to increase funds by raising council tax will mean that the biggest increases will not necessarily be in the areas most in need.

Criminal justice services

Criminal justice services have been heavily disrupted by the pandemic. Courts have struggled to run in-person trials while maintaining social distancing. Prisoners have at times been virtually confined to their cells, with greatly reduced access to the kinds of rehabilitative activity normally provided. The police have had to work differently to enforce pandemic restrictions, in addition to responding to crime, during the various national and local lockdowns.

The most visible impact of the pandemic has been on criminal courts. Despite greater use of remote hearings and other changes to working practices, the backlog of cases has grown dramatically, reaching record levels of just over 60,000 in the crown court.[25]

The new spending settlements for the Home Office and MoJ – which are responsible for the police, criminal courts, and prisons – provide a substantial rise in spending over the next three years. The MoJ will see spending rise an average of 2.6% in real terms per year between 2019/20 and 2024/25, and the Home Office will see an average annual increase of 3.9% over the same period. For both departments, spending is frontloaded with the largest year-on-year increases occurring in 2022/23.

If police spending rises in line with the total Home Office budget, then the new settlement will mean police spending per person increases over the rest of this parliament. If crime and non-crime demands on the police rise in line with the population, then this should be more than enough to meet demand. The government allocated £18m in 2022/23 and £12m in 2023/24 and 2024/25 to tackle fraud and £42m for new programmes to prevent crime and drug misuse. The government committed another £540m by to recruit the remaining 8,000 officers of the uplift programme, which should be enough as they are currently on track to hit the target of 20,000 extra officers.

If criminal courts funding rises in line with the total MoJ budget, then the new settlement will provide enough to hear the number of new cases entering the courts over the rest of parliament. The government also allocated £477m to fund the criminal justice system’s recovery from Covid and reduce the number of cases waiting to be heard to 53,000. This target is higher than the number of cases waiting to be heard pre-pandemic, although the funding may actually be enough to return backlogs to pre-pandemic levels. We estimate that it would cost £311m to return the criminal court backlog to pre-pandemic levels, although this does not include other costs, such as higher legal aid spending and Crown Prosecution Service spending, which the NAO suggests could be even larger.[26] The main constraint in the courts will be judicial capacity, which will slow the speed at which courts can clear outstanding cases. Even if criminal courts are able to operate at the peak level of 2015/16 from September 2021, the backlog would only be reduced pre-pandemic levels by December 2023. The government may therefore need to attract more judges and barristers to work on crime, which could be very expensive.

If prison funding also rises in line with the total MoJ budget, spending per prisoner will be slightly lower in 2024/25 than in 2019/20 – as the number of prisoners is expected to be 14.5% higher in 2024/25 than in 2019/20. This is partly because the number of prisoners was set to increase before the pandemic as a result of the government’s plans to hire an additional 20,000 police officers, which will increase the number of people facing criminal charges, and the number of people sentenced to prison.

The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill will also create further costs for prisons if passed. The MoJ may need to allocate more money to prisons to ensure they can accommodate the expected increase in prisoners without having to reduce costs in prisons, by reducing officer-prisoner ratios or cutting rehabilitation programmes. The settlement also leaves little room for pay rises.

- HM Government, Build Back Better: Our plan for health and social care (CP 506), The Stationery Office, September 2021

- Spending Review 2010 figures are the average annual change in real-terms spending between 2009/10 and 2014/15; Spending Review 2015 figures are the average annual change in real-terms spending between 2015/16 and 2019/20. Spending Review 2021 figures are the projected average annual change in the NHS England five-year settlement, schools settlement, Ministry of Justice settlement, Home Office settlement, and local government spending power excluding grants for social care

- Maddox B, Kidney Bishop T and Wheatley M, The 2019 Spending Review: How to run it well, Institute for Government, September 2019, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/2019-spending-review

- HM Government, Build Back Better: Our plan for health and social care (CP 506), The Stationery Office, September 2021

- Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street, ‘PM statement to the House on the Integrated Review: 19 November 2020’, 19 November 2020, www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-statement-to-the-house-on-the-integrated-review-19-november-2020

- Department for Education and Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street, ‘Prime Minister boosts schools with £14 billion package’, 30 August 2019, www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-boosts-schools-with-14-billion-package

- Rishi Sunak, ‘Spending Review 2020 speech’, 25 November 2020, www.gov.uk/government/speeches/spending-review-2020-speech

- Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP, ‘Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021 Speech’, 27 October 2021, www.gov.uk/government/speeches/autumn-budget-and-spending-review-2021-speech

- Rocks S, Boccarini G, Charlesworth A, Idriss O, McConkey R and Ratchet-Jacquet L, ‘Health and social care funding to 2024/25: Slide Deck of Key findings’, Health Foundation, September 2021, p. 8, www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/health-and-social-care-funding-to-2024-25

- Rocks S, Boccarini G, Charlesworth A, Idriss O, McConkey R and Ratchet-Jacquet L, ‘Health and social care funding to 2024/25: Slide Deck of Key findings’, Health Foundation, September 2021, p. 8, www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/health-and-social-care-funding-to-2024-25

- Sajid Javid MP, ‘NHS staff to receive 3% pay rise’, 21 July 2021, www.gov.uk/government/news/nhs-staff-to-receive-3-pay-rise

- Warner M and Zaranko B, ‘Pressure on the NHS’, in Institute for Fiscal Studies, IFS Green Budget 2021, p. 264, www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/6-Pressures-on-the-NHS-.pdf

- Rocks S, Boccarini G, Charlesworth A, Idriss O, McConkey R and Ratchet-Jacquet L, ‘Health and social care funding projections 2021’, Health Foundation, September 2021, p. 74, www.health.org.uk/publications/health-and-social-care-funding-projections-2021

- HM Treasury, Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021 (HC 822), The Stationery Office, October 2021, p. 94

- The Health Foundation, Health Foundation submission to the Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021, September 2021, pp. 9, 13, www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-10/202109_Health%20Foundation%20submission%20to%20the%20Autumn%20Budget%20and%20Spending%20Review%202021.pdf

- Ben Zaranko, Spending review 2021: Austerity over but not undone, Institute for Fiscal Studies, p.10 https://ifs.org.uk/uploads/Autumn-Budget-2021-Austerity-over-but-not-undone-Ben-Zaranko.pdf

- HM Treasury, Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021 (HC 822), The Stationery Office, October 2021, p. 96

- Andrews J, Archer T, Crenna-Jennings W, Perera N and Sibieta L, Education recovery and resilience in England: Phase two report, October 2021, www.epi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/EPI-Education-Recovery-Report-2__.pdf

- Wright O and Courea E, ‘Sir Kevan Collins accuses Boris Johnson of failing generation of children’, The Times, 2 June 2021

- HM Treasury, Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021 (HC 822), The Stationery Office, October 2021, p. 108

- Local Government Association, ‘LGA: Local services will cost at least £8bn more by 2024, which cannot be funded by council tax alone’, 1 October 2021, www.local.gov.uk/about/news/lga-local-services-will-cost-least-ps8bn-more-2024-which-cannot-be-funded-council-tax

- Ogden K, Philips D and Sion C, ‘What’s happened and what’s next for councils?’, in Institute for Fiscal Studies, IFS Green Budget 2021, p. 311, www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/7-What%E2%80%99s-happened-and-what%E2%80%99s-next-for-councils-.pdf

- HM Treasury, Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021 (HC 822), The Stationery Office, October 2021, p. 27

- Office for Budget Responsibility, Economic and fiscal outlook October 2021 (CP 545), The Stationery Office, October 2021, p. 105

- HM Treasury, Autumn Budget and Spending Review 2021 (HC 822), The Stationery Office, October 2021, p. 109

- MoJ, Criminal court statistics quarterly, April to June 2021, 30 September 2021, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/criminal-court-statistics-quarterly-april-to-june-2021/criminal-court-statistics-quarterly-april-to-june-2021

- Comptroller and Auditor General, Reducing the backlog in criminal courts, Session 2021–22, HC 732, National Audit Office, 20 October 2021

- Topic

- Public services

- Keywords

- Health NHS Schools Local government

- Publisher

- Institute for Government