Brexit dividend

This explainer sets out how any Brexit dividend (or otherwise) is reflected in the government’s official independent forecasts prepared by the OBR.

Is there a Brexit dividend?

Ever since Vote Leave’s infamous claim during the 2016 referendum campaign that leaving the European Union (EU) would allow the UK to spend an extra £350m per week on the NHS, the question of what leaving the EU would mean for public finances has surfaced often. In short, is there a ‘Brexit dividend’?

This explainer sets out what will influence this, and how any Brexit dividend (or otherwise) is reflected in the government’s official independent forecasts prepared by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

The impact of leaving the EU on the public finances depends on three components: the effect on the economy, the UK’s net contributions to the EU, and tariff revenues.

The economic impact

Any change in economic growth has a big impact on the public finances. When the economy grows, so too do tax revenues (for example, if people start earning more, income tax receipts rise). Though the same is true of the reverse, of course. Leaving the EU means shaking up the UK’s relationship with its biggest trading partner and so is likely to affect the economy.

The economic impact of the UK leaving a trading bloc of which it has been a part for four decades is inherently uncertain. But most economists agree that the UK economy is likely to be smaller in the medium term outside of the EU than it would have been inside it. The underlying rationale for this conclusion is that the UK will become a less open trading economy and so a less attractive location for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) overall – assuming there are more barriers to trade with the EU. More open trading economies, and those with more FDI, tend to grow more quickly.

This rationale also suggests that, in general, a ‘closer’ post-Brexit trading relationship with the EU – that is, one that more closely resemble the terms of full membership – would be less economically damaging than a more distant one. These have often been described as a ‘soft’ or ‘hard’ Brexit. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research’s (NIESR) pre-referendum forecasts found that a close EEA-style (European Economic Area) relationship would lead to the UK economy being 1.8% smaller than it would be remaining in the EU, while failure to reach a deal (meaning trading under less favourable World Trade Organization rules) would lead to a 3.2% reduction.

In November 2016, the OBR downgraded its forecast (the first following the referendum) as a result of the vote to leave. It judged that the decision was likely to reduce cumulative growth in potential output (effectively, permanent economic growth) between 2016 and 2021 by 2.4ppt, and increase the forecast deficit by £15.2bn a year (0.65% of GDP). This £15.2bn included the impact of expected lower migration, lower incomes and higher inflation, along with the (offsetting) impact of lower interest rates and lower investment.

The OBR has not updated its assessment of the effect of Brexit since. It may not. The more time passes since the Brexit vote, the harder it becomes to construct a ‘no-Brexit counterfactual’ – what would have happened had the UK had voted to remain. However, its 2016 assessment seems to have been reasonably accurate. The UK economy has grown roughly 2ppts slower than pre-referendum forecasts projected, while other comparable countries (both EU and non-EU members) have grown in line with those earlier forecasts.

However, the OBR’s initial assessment was predicated on a relatively close post-Brexit trading relationship. If, as seems likely, the future relationship is more distant, the forecasts may be revised downwards further to reflect this.

Net contributions

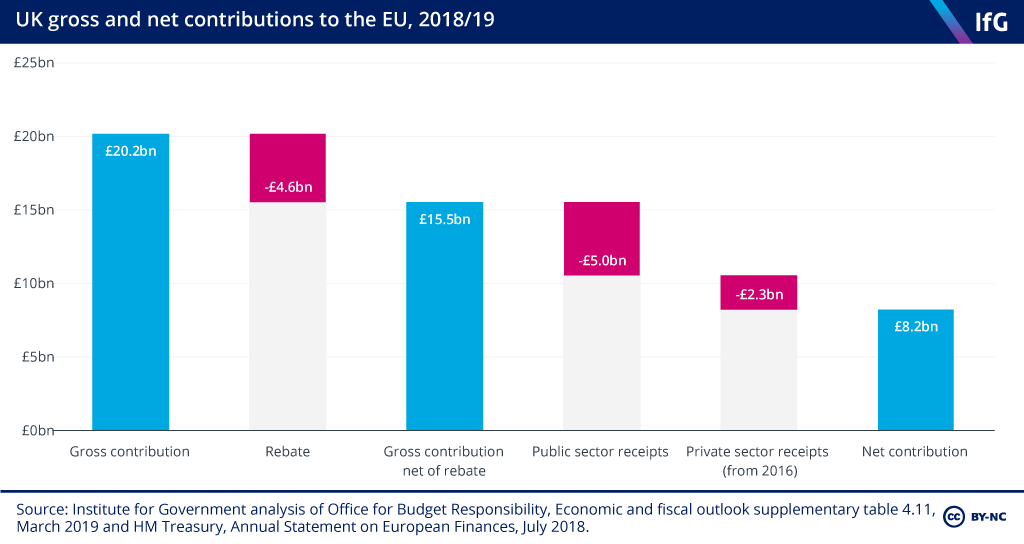

During its time as a member, the UK paid more to the EU in annual contributions than it received back in payments from it. In 2018/19, the UK’s gross EU contribution was £20.2bn – £388m per week – which was immediately offset by the rebate (a discount for the UK negotiated by Margaret Thatcher in 1985) of £4.6bn. This means that the UK sent £15.6bn to the EU in that year.

However, both the UK government and private sector organisations also receive EU funds – for example, structural funds for deprived areas, Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) payments for farms and research grants for universities and academic bodies. In total, payments from the EU to the public sector amounted to £5.0bn in 2018/19. In 2016 (the latest year for which data is available), the private sector in the UK received EU funds worth £2.3bn.

Assuming private sector receipts have remained stable over the past few years, this would imply that the UK’s annual net contribution was around £8–9bn per year.

Over the next few years, under the terms of the Withdrawal Agreement, the UK will continue to make payments to the EU in respect of commitments made before it left (for example, ongoing pension liabilities). These payments are largest over the next few years – €7.5bn (£6.3bn) in 2021, declining to €1.3bn (£1.1bn) in 2024 – then are negligible beyond the mid-2020s.

In previous forecasts, the OBR has assumed that all ended EU contributions would be recycled into other (unspecified) spending. In fact, the government could replace all spending from the EU in the UK, such as farm subsidies, and still have an amount equal to £8–9bn per year (in 2020 prices) from the mid-2020s left over.

Tariff revenues

Part of the UK’s contributions to the EU are the tariff revenues collected by the UK as part of the customs union, collected when goods enter the EU single market via the UK. In 2020/21, the UK collected tariffs worth £3.4bn, and the EU provided a rebate of £0.7bn (notionally to cover the cost of collecting those tariffs). These tariff revenues contribute £2.7bn of the £8–9bn net contribution set out above.

The UK is leaving the EU customs union, which means that it will no longer collect tariff revenues on behalf of the trading bloc. In future, the UK will set its own tariff regime, and patterns of trade will change. If the UK sets higher tariffs – including imposing tariffs on EU trade – it could raise more in revenue than the £3.4bn currently collected. If, on the other hand, the UK adopts lower tariffs than the EU – at the extreme adopting ‘unilateral free trade’ and imposing no tariffs at all – tariff revenue could be very low.

Deciding on how to approach tariffs highlights the tension between the government’s focus on the direct and indirect public finance impacts. A punitive (high) tariff regime would mean more revenue is raised on goods at the point of entry; this is a direct financial impact. But doing so would likely mean lower economic growth as it would make the UK a less open economy (as discussed above). It would likely cause other indirect revenues to fall and the deficit to rise too, and so would result in a negative wider economic impact.

Overall assessment

An estimate of the negative economic impact has already been factored into the official forecasts, but the upside – from no longer making EU contributions – is not, as that money is currently floating around as ‘unallocated’ spending in the fiscal forecasts.

That said, while the economic effects are uncertain, forecasts suggest that a negative indirect impact from lower economic growth would outweigh any positive direct impact of the UK no longer paying contributions into the EU budget or setting its own tariffs. It is, then, unlikely that there the UK is to enjoy any meaningful ‘Brexit dividend’.