Secondary legislation: how is it scrutinised?

This explainer outlines the ways parliament scrutinises secondary legislation.

This explainer outlines the ways parliament scrutinises secondary legislation. Read an overview of what secondary legislation is and what it is used for.

Additional steps apply to the scrutiny of some Brexit secondary legislation under the EU (Withdrawal) Act 2018.

Secondary legislation scrutiny procedures

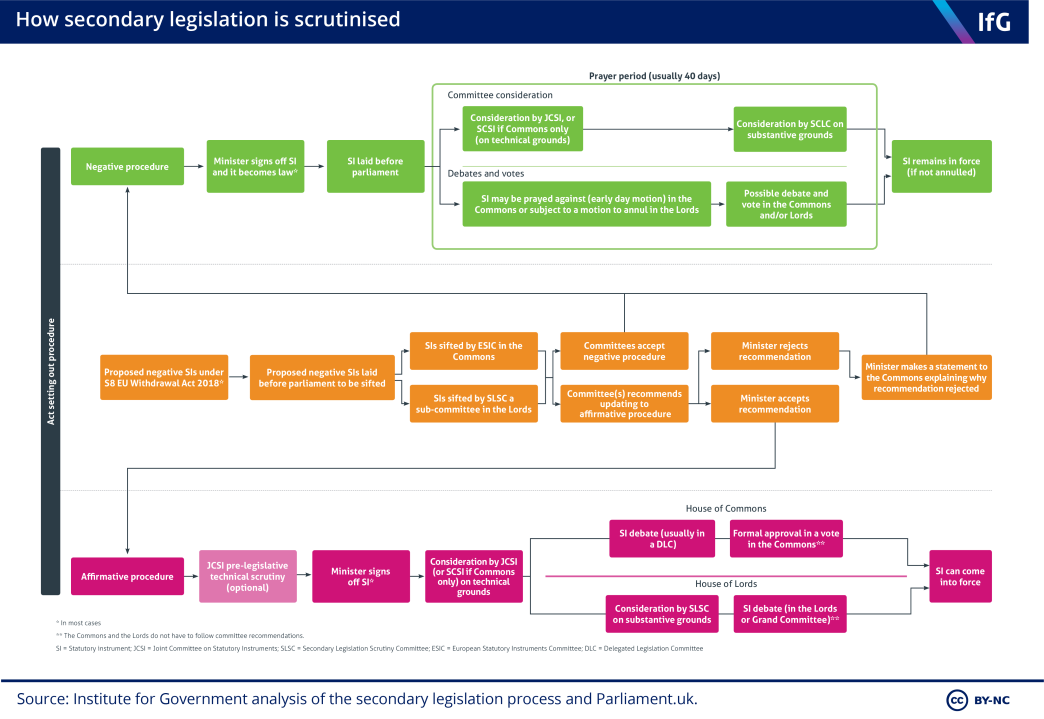

Parliament usually scrutinises secondary legislation through one of two routes, the negative and affirmative procedures.

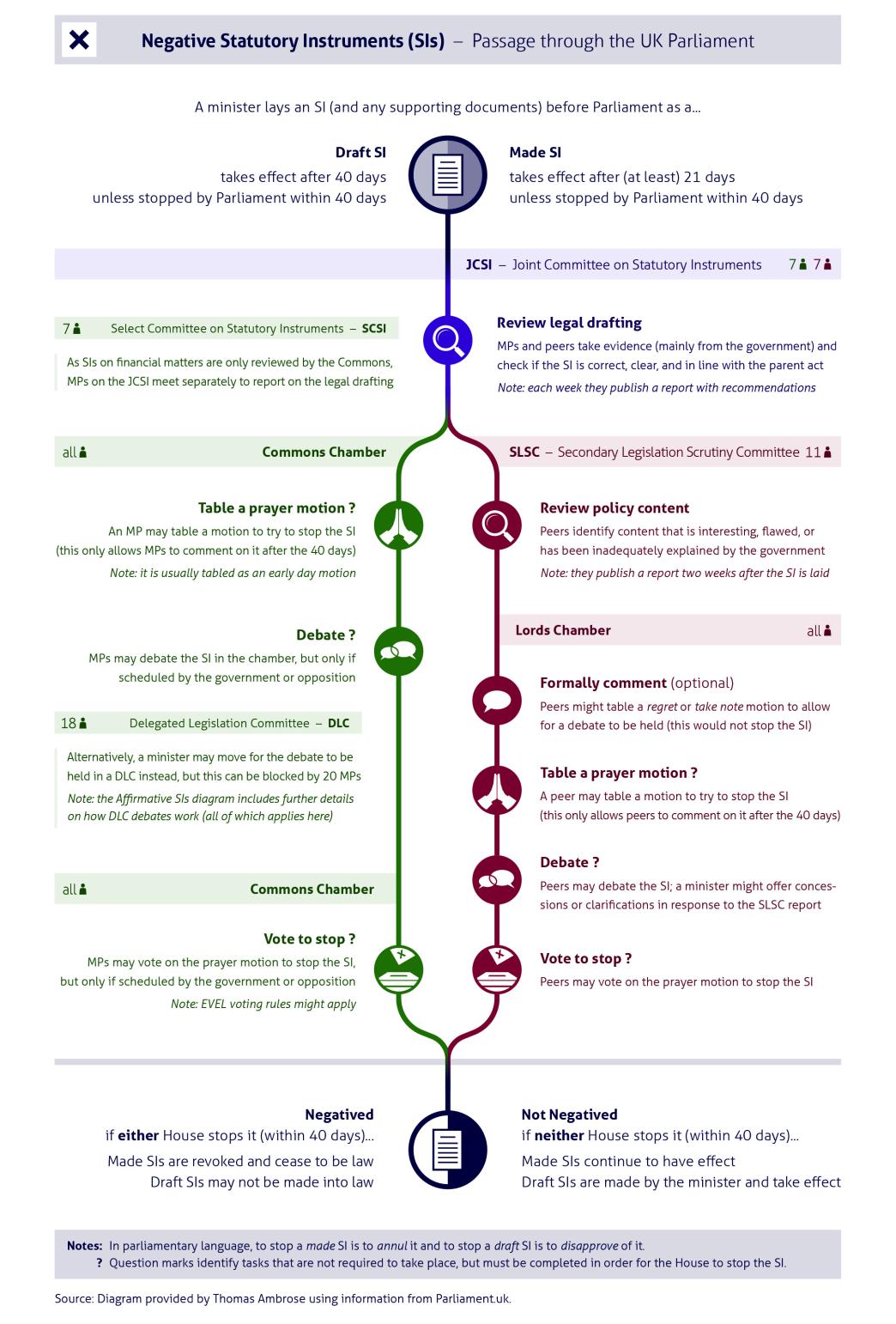

1. The negative procedure

Around 75% of secondary legislation is usually made using the negative procedure. Under this procedure, most instruments are made (signed off) by the relevant minister and then laid before parliament. It then becomes law unless it is actively voted down (annulled) within a set period. This period is usually 40 days, excluding any time during which parliament is dissolved or prorogued (such as before an election), or when both Houses are adjourned for more than four days. In the Commons, a piece of secondary legislation can be annulled if the House agrees a motion to annul (these are referred to as a ‘prayer’ and take the form of an ‘Early Day Motion’). Any MP may table such a motion, but the government is under no obligation to find time for it to be debated in the House. In practice only those tabled by the Official Opposition, or commanding significant support in parliament, are likely to be debated and voted upon.

In the Lords, peers may also table a motion to annul a piece of secondary legislation. These are more likely to be debated as the government has less control of parliamentary time in the Lords. Peers may also table a broader range of motions, including motions of regret, which allow concerns to be expressed without invalidating the legislation.

While the negative procedure gives parliament a theoretical veto over secondary legislation, in reality this power is rarely used. The last time the House of Commons prayed against secondary legislation was in 1979 , while the Lords have not rejected a negative instrument since 2000.

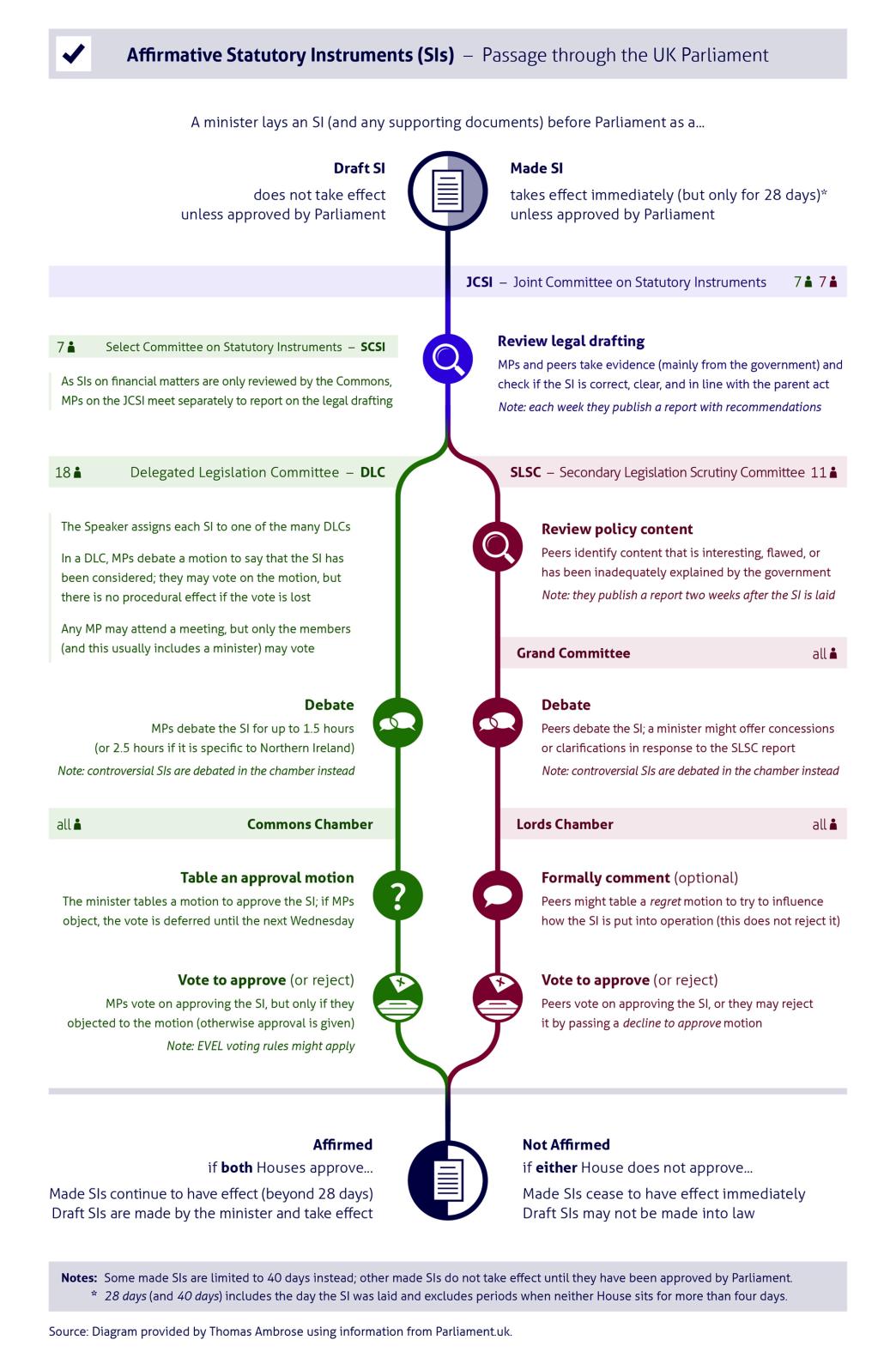

2. The affirmative procedure

Around 25% of secondary legislation is usually made using the ‘affirmative’ procedure. Under this procedure, both Houses must actively approve a piece of secondary legislation before it can become law (although secondary legislation on financial matters needs to be approved by the Commons, as the elected nature of the Commons means it has precedence over the Lords on financial matters).

In the Commons, most secondary legislation subject to the affirmative procedure is debated in Delegated Legislation Committees (DLCs). DLCs are usually composed of between 16-18 (usually non-expert) MPs, appointed ad hoc for each instrument (or group of instruments), and chaired by a member of the Panel of Chairs (the group of MPs eligible to chair Public Bill Committees). Debates in DLCs can last up to 90 minutes (or 150 minutes if the piece of secondary legislation relates only to Northern Ireland), but are usually much shorter. DLCs typically debate and agree a motion that they have ‘considered’ a piece of secondary legislation without holding a formal vote. Once this has happened, a motion to approve a piece of secondary legislation is put ‘forthwith’ to the House of Commons. This means MPs will vote on whether to approve the instrument(s) on a different day to the DLC, and without debate. While secondary legislation subject to affirmative procedure in the Commons is usually automatically referred to a DLC, a small amount is instead debated, and voted on, on the floor of the House.

In the Lords, affirmative secondary legislation is either debated in the Chamber, or in Grand Committee. In the Chamber, peers debate and vote on whether to approve the piece of secondary legislation. If the legislation is debated in Grand Committee, peers debate a motion to ‘consider’ the piece of secondary legislation, and a formal motion to approve it is put to the full Chamber on a later day.

Although the affirmative procedure gives parliament a greater say over secondary legislation, the last time the House of Commons failed to pass an affirmative instrument was in 1978, while the House of Lords last failed to approve a piece of affirmative legislation in 2015, sparking much controversy.

A small proportion of secondary legislation is subject to no procedure at all, or merely a requirement that the legislation be laid before parliament.

This means the legislation will become law on the date stated in the instrument, without any action from MPs or peers. Examples of secondary legislation that may fall under this category include Commencement Orders, which allow the government to ‘turn on’ parts, or all, of an Act of parliament that has been granted Royal Assent, but where parliament has delegated the power to decide when the legislation should come into effect.

Occasionally, the act delegating power to make secondary legislation will specify a variation on these procedures. For instance, the ‘super affirmative procedure’ provides for greater parliamentary scrutiny, and involves a minister presenting the proposed piece of secondary legislation and a statement explaining what it would do to parliament before it is formally laid. This gives parliamentary committees an opportunity to make recommendations, and the government to make changes, before parliament is asked to approve it. Once formally laid, the instrument must be actively approved by parliament in the same way as the affirmative procedure.

In some cases, secondary legislation that would usually be made under the affirmative procedure may need to come into force more quickly, such as when the government needs to respond to a crisis. In these cases, the parent act may provide for secondary legislation to be made (signed off by the minister) and come into force immediately, using the ‘made affirmative’ or ‘urgent’ procedure. However, the instrument will not usually remain in force unless approved by parliament within a statutory period (usually 28 or 40 days, excluding periods when parliament is dissolved, prorogued or adjourned for more than 4 days) – effectively providing a form of retrospective approval. Regulations enforcing the coronavirus lockdown. England and Wales under the Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984 were made using this procedure.

Secondary legislation cannot usually be amended by parliament, except in rare cases where the parent act allows for amendment.

The role of parliamentary committees in scrutinising secondary legislation

Permanent parliamentary committees also play an important role in scrutinising secondary legislation, assessing both powers to make secondary legislation, and how they are subsequently exercised.

-

In scrutinising the appropriateness of delegating powers

In both the Commons and the Lords, committees can influence the debate around the appropriateness of delegated powers and the scrutiny attached to them. These committees consider bills going through parliament, but not consider individual pieces of secondary legislation.

- The Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee (DPRRC) is a Lords committee which reports on whether a bill inappropriately delegates legislative power, or whether they subject the exercise of legislative power to an inappropriate degree of parliamentary scrutiny.

- The Constitution Committee (CC) is a Lords committee which examines the constitutional implications of public bills. This can include raising concerns if a bill is thought to delegate too much power to the executive.

- The Procedure Committee (PC) is a Commons committee that considers the practice and procedure of the House. This can involve highlighting concerns about the procedures for passing secondary legislation and making recommendations for reform.

- In scrutinising the exercise of delegated powers

In both the Commons and Lords, specific committees exist to scrutinise secondary legislation.

- The Joint Committee on Statutory Instruments (JCSI) is composed of members of both Houses. It meets weekly to consider all secondary legislation. The JCSI mainly focuses on the technical quality of legislation, such as whether a it is well-drafted. Where the JCSI has concerns, it may choose to bring an instrument to the attention of both Houses. The JCSI also offers ‘pre-legislative’ scrutiny of the government’s draft secondary legislation, with the aim of highlighting concerns before the legislation is laid before parliament.

- The Select Committee on Statutory Instruments (SCSI) plays the same role as the JCSI, but is comprised exclusively of Commons members. It looks at the technical quality of secondary legislation that is not considered by the Lords – mainly that relating to financial matters.

The Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee (SLSC) is a Lords committee that examines all secondary legislation laid before the Lords. The SLSC focuses on the policy merits of secondary legislation, and may choose to bring it to the attention of the House on several grounds (for example, that the explanatory material accompanying it isn’t good enough, or that it ‘imperfectly’ achieves its objective). There is currently no Commons equivalent of the SLSC.

- Keywords

- Accountability

- Publisher

- Institute for Government