Public bodies reform

The Declaration on Government Reform published in June 2021 committed the government to “commence a review programme for Arm’s Length Bodies".

What are public bodies?

A public body is “a formally established organisation that is (at least in part) publicly funded to deliver a public or government service, though not as a ministerial department”. undefined Cabinet Office, Classification of Public Bodies: Guidance for Departments, Gov.uk, April 2016, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/519571/Classification-of-Public_Bodies-Guidance-for-Departments.pdf, p. 5. They include delivery bodies like NHS England, regulators like the Competition and Markets Authority, and broadcasters like the BBC. For more on the different categories of public bodies, see our public bodies explainer.

Why does the UK have public bodies?

The Cabinet Office’s guidance on setting up new public bodies states that functions should only be performed by a public body if they pass one of three tests: undefined Cabinet Office, Classification of Public Bodies: Guidance for Departments, Gov.uk, April 2016, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/519571/Classification-of-Public_Bodies-Guidance-for-Departments.pdf, p. 5.

- Is this a technical function, which needs external expertise to deliver?

- Is this a function which needs to be, and be seen to be, delivered with absolute political impartiality?

- Is this a function that needs to be delivered independently of ministers to establish facts and/or figures with integrity?

The history of public bodies reform

Many public bodies have existed for centuries, and government has often found it difficult to keep track of them. The number and perceived wastefulness of public bodies became a target of political criticism in the 1970s, particularly from the Conservative opposition. undefined Cabinet Office, Classification of Public Bodies: Guidance for Departments, Gov.uk, April 2016, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/519571/Classification-of-Public_Bodies-Guidance-for-Departments.pdf, p. 5. After the 1979 election, the Conservative governments of the 1980s and 1990s reduced the number of state-controlled industries and the number of non-departmental public bodies (NDPBs).

However, the same governments also expanded the ‘agencification’ of many civil service functions. The Next Steps report published in 1988 by the prime minister’s efficiency unit recommended splitting off around three quarters of civil service staff into executive agencies, resulting in the launch of 120 agencies, including the Met Office and the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Authority. For prime minister Margaret Thatcher this was a means of introducing new, private sector management techniques into government. undefined Cabinet Office, Classification of Public Bodies: Guidance for Departments, Gov.uk, April 2016, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/519571/Classification-of-Public_Bodies-Guidance-for-Departments.pdf, p. 5. Some academics have also argued that it was an attempt to circumvent civil servants, and even ministers, accused of resisting change by moving functions outside of their direct control. undefined Cabinet Office, Classification of Public Bodies: Guidance for Departments, Gov.uk, April 2016, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/519571/Classification-of-Public_Bodies-Guidance-for-Departments.pdf, p. 5.

New Labour opposed the proliferation of ‘quangos’ in opposition but found them quite convenient in government, using bodies like the Low Pay Commission and the Youth Justice Board to run many of its flagship programmes. undefined Cabinet Office, Classification of Public Bodies: Guidance for Departments, Gov.uk, April 2016, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/519571/Classification-of-Public_Bodies-Guidance-for-Departments.pdf, p. 5. When Labour was succeeded by the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition in 2010, public bodies reform again rose up the agenda. Led by the minister for the Cabinet Office, Francis Maude, government launched a ‘bonfire of the quangos’, which involved reviews of every NDPB to check if they were still required, and the closure of at least 106 public bodies by 2012. undefined Cabinet Office, Classification of Public Bodies: Guidance for Departments, Gov.uk, April 2016, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/519571/Classification-of-Public_Bodies-Guidance-for-Departments.pdf, p. 5. However, the pace of change has slowed since the 2015 election, as political attention has been focused on other challenges, including the UK’s departure from the EU.

How has the number of public bodies changed?

Historic data on the number of public bodies is quite limited. The most comprehensive list comes from the Office for National Statistics’ (ONS) database, although this has only been collected for around a decade. This list suggests that the number of “central government organisations", excluding ministerial departments and bodies accountable to devolved administrations, fell by 22% in the last decade, from 656 bodies in August 2011 to 511 in November 2021. undefined Cabinet Office, Classification of Public Bodies: Guidance for Departments, Gov.uk, April 2016, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/519571/Classification-of-Public_Bodies-Guidance-for-Departments.pdf, p. 5. The ONS data also suggests the number of public non-financial corporations fell by 24% over the same period. undefined Cabinet Office, Classification of Public Bodies: Guidance for Departments, Gov.uk, April 2016, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/519571/Classification-of-Public_Bodies-Guidance-for-Departments.pdf, p. 5.

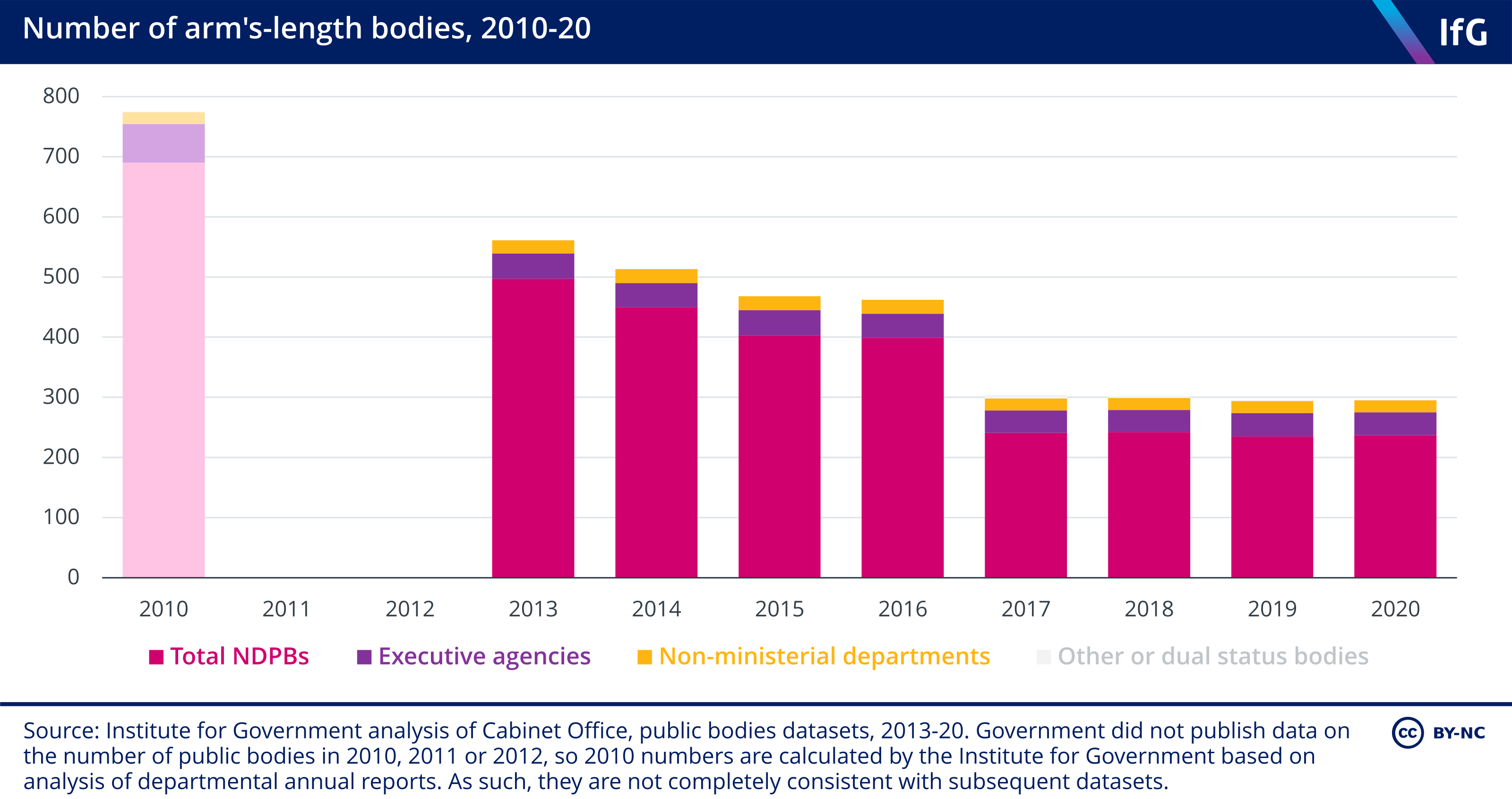

The Cabinet Office also tracks the number of arm’s-length bodies (ALBs), a subset of public bodies, whose numbers have fallen much faster. According to this data and previous Institute for Government analysis, undefined Cabinet Office, Classification of Public Bodies: Guidance for Departments, Gov.uk, April 2016, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/519571/Classification-of-Public_Bodies-Guidance-for-Departments.pdf, p. 5. the number of ALBs has more than halved, from 800 in 2010 to just 295 in 2020. Especially in recent years, this change has been concentrated amongst NDPBs, where numbers have fallen by around two thirds in the same period. The number of non-ministerial departments, however, is the same as it was in 2010, and while there has been a significant drop in the number of executive agencies, nearly all of this took place between 2010 and 2013.

The difference between the rate of change in these two datasets partly reflects the fact that the government has reduced the number of ALBs by recategorising organisations as public corporations or other forms of public body that it is not obliged to report on. The ONS data is therefore closer to showing the true overall picture on public bodies reform over the past ten years than the Cabinet Office’s.

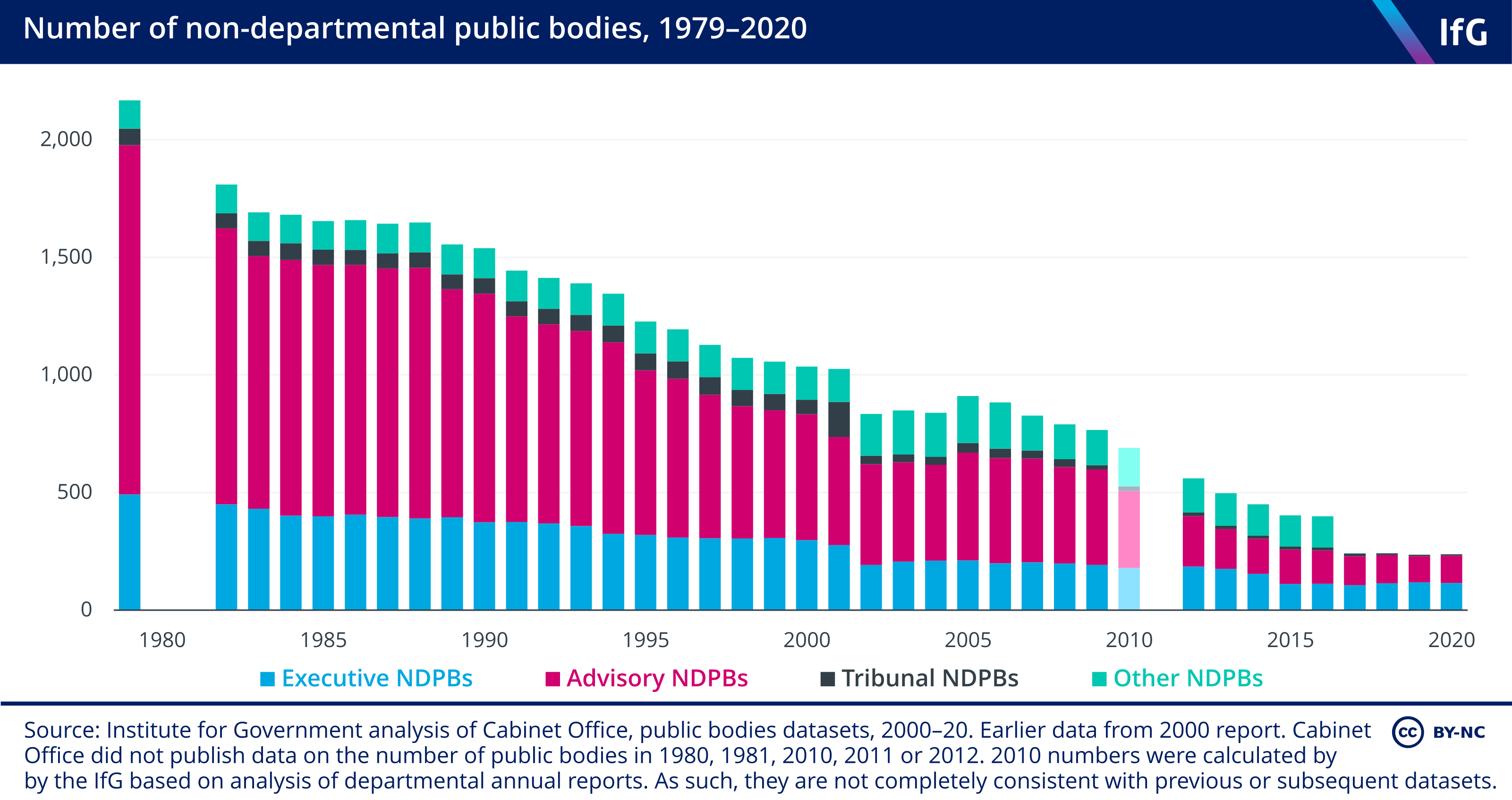

The Cabinet Office also has data on the number of NDPBs alone, which stretches much further back in time. This shows that the number of NDPBs has consistently fallen over the past 40 years, from over 2,000 in 1979 to just 237 in 2020. The largest fall has been in advisory NDPBs, whose numbers have reduced by well over 90% between 1979 and 2020. undefined Cabinet Office, public bodies reports 1999 to 2020, Gov.uk, last updated 15 July 2021, retrieved 9 December 2021, www.gov.uk/government/collections/public-bodies. Data before 1999 is summarised in the 1999 report. This is partly because these bodies are easier to abolish than other forms of body (they often have no permanent staff, and are less likely to perform essential or statutory functions), and many have been reconstituted as expert committees within departments. undefined Cabinet Office, public bodies reports 1999 to 2020, Gov.uk, last updated 15 July 2021, retrieved 9 December 2021, www.gov.uk/government/collections/public-bodies. Data before 1999 is summarised in the 1999 report.

What happened to abolished public bodies?

The fate of public bodies that have been abolished varies. Some, especially those with purely advisory functions, were deemed to be no longer needed. Others had their functions privatised, like Royal Mail and BT.

However most of the recently abolished bodies have either been recategorised as another form of public body, or merged, rather than fully abolished. According to National Audit Office analysis, of the bodies that were removed from the Cabinet Office database between 2016 and 2019, 143 were recategorised, 35 were closed and replaced or merged, and just seven were closed without being replaced. undefined Comptroller and Auditor General, Central Oversight of Arms-length Bodies, National Audit Office, Session 2021/22, HC 297, 23 June 2021, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Central-oversight-of-Arms-length-bodies.pdf, p. 16. For example, nine academic research councils were combined into one after the Nurse Review, undefined Comptroller and Auditor General, Central Oversight of Arms-length Bodies, National Audit Office, Session 2021/22, HC 297, 23 June 2021, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Central-oversight-of-Arms-length-bodies.pdf, p. 16. leading to a reduction in numbers but not a reduction in the functions performed by public bodies.

Some high-profile public bodies have been replaced by functions moving into departments themselves. For instance UK Border Force was closed in 2012 with the Home Office taking on its functions.

How has spending on public bodies changed?

Public bodies reform programmes have usually struggled to reduce staffing and funding of public bodies at the same rate as numbers have reduced – in part because some bodies have simply been merged, while others may take on new functions to cover for abolished bodies. For instance, while the number of executive NDPBs fell by half under Margaret Thatcher and John Major, their government-funded spending nearly doubled after accounting for inflation.

Details of public funding for ALBs more broadly have only been available since 2013. These figures show government funding of public bodies has remained reasonably steady over the past eight years, despite the fall in the total number of ALBs. However, this masks changes in the composition of spending. Funding for executive NDPBs (excluding NHS England) fell in real terms under the coalition government, but it has risen consistently since 2015. On the other hand, government funding for executive agencies was 16% lower in 2020 than in 2015. undefined Comptroller and Auditor General, Central Oversight of Arms-length Bodies, National Audit Office, Session 2021/22, HC 297, 23 June 2021, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Central-oversight-of-Arms-length-bodies.pdf, p. 16.

What is happening now on public bodies reform?

After 2016 governments initially devoted less attention to reforming public bodies, focusing on other issues like Brexit and coronavirus. But the Declaration on Government Reform published in June 2021 committed the government to “commence a review programme for Arm’s Length Bodies and increase the effectiveness of their departmental sponsorship, underpinned by clear performance metrics and rigorous new governance and sponsorship standards.” undefined Comptroller and Auditor General, Central Oversight of Arms-length Bodies, National Audit Office, Session 2021/22, HC 297, 23 June 2021, www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Central-oversight-of-Arms-length-bodies.pdf, p. 16.

- Topic

- Public bodies

- Department

- Cabinet Office

- Publisher

- Institute for Government