Public bodies

Public bodies deliver a public or government service, though not as a ministerial department.

What is a public body?

The Cabinet Office defines a public body as “a formally established organisation that is (at least in part) publicly funded to deliver a public or government service, though not as a ministerial department”. undefined Cabinet Office, ‘Classification Of Public Bodies: Guidance For Departments’, Gov.uk, April 2016, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/519571/Classification-of-Public_Bodies-Guidance-for-Departments.pdf, p. 5. In fact, some public bodies are funded from user fees and charges and do not receive any direct public money. Public bodies generally operate with some independence from central government. For instance, many have their own boards and CEOs, and some are expected to scrutinise and critique government when appropriate.

A subset of public bodies are categorised by the Cabinet Office as ‘arm’s-length bodies’ (ALBs): these are bodies that are primarily accountable to UK government ministers (rather than parliament or devolved government ministers), are not financial corporations which primarily operate by selling their goods and services, undefined Cabinet Office, ‘Classification Of Public Bodies: Guidance For Departments’, Gov.uk, April 2016, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/519571/Classification-of-Public_Bodies-Guidance-for-Departments.pdf, p. 5. and are officially classified as such by the Cabinet Office. This can be an arbitrary definition, as some bodies are recategorised into or outside this category without a significant change in governance or function. undefined Cabinet Office, ‘Classification Of Public Bodies: Guidance For Departments’, Gov.uk, April 2016, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/519571/Classification-of-Public_Bodies-Guidance-for-Departments.pdf, p. 5. The classification matters, however, because the Cabinet Office only collects data on ALBs rather than all public bodies. ALBs are responsible for the majority of spending by public bodies.

What do public bodies do?

Public bodies have a wide range of responsibilities. The scope of their work is as broad as the government defines it to be based on ministers’ ambitions and obligations. Public bodies’ activities range from investigating air crashes, regulating new varieties of plant, manufacturing currency, managing radioactive waste, issuing patents and trademarks, to inspecting prisons. They also include a set of national institutions such as the British Library, nine National Park Authorities, and at least 17 major museums including the Natural History Museum and the British Museum.

Many public bodies perform executive functions, where the organisation manages or delivers something on behalf of the government. Others have regulatory functions – setting and enforcing rules and standards, often through processes of inspection or audit. This category includes bodies that regulate government or other ALBs. For instance the Information Commissioner’s Office monitors how government and other public bodies handle Freedom of Information requests. Some public bodies have advisory functions; these tend to have the most independence from ministerial control. Lastly there are tribunal functions, where certain public bodies have jurisdiction in an area of law, and work to resolve legal claims or disputes. Some public bodies focus on just one of these functions, others have a variety of roles.

Why does the government have public bodies?

Public bodies have existed for centuries in one form or another – the British Museum, for instance, was established in 1753. They proliferated in the middle of the 20th century, but have declined fairly steadily in number since the 1970s (although funding and staffing levels have not declined to the same extent).

Separating government functions away from central departments can help public bodies to recruit and develop the types of specialist knowledge that might otherwise be lost in a more general department. It also allows for some functions to be conducted with a degree of independence from government, such as when the Bank of England sets interest rates, or the Equality and Human Rights Commission pursues investigations.

How are public bodies funded?

The money for public bodies comes from a variety of sources. Most are predominantly funded by the government, but a significant number partly or wholly fund themselves through industry levies or by asking customers to pay for services. For example, the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) is primarily self-funded through customers paying for driving licenses. Of the 295 ALBs on which the Cabinet Office keeps data, in 2019/20 around a fifth (67) received no government funding. undefined Cabinet Office, ‘Classification Of Public Bodies: Guidance For Departments’, Gov.uk, April 2016, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/519571/Classification-of-Public_Bodies-Guidance-for-Departments.pdf, p. 5.

What are the different types of public body within central government?

The Cabinet Office classifies public bodies according to the “the degree of freedom that body needs from ministerial control to perform its functions”. There are three types of public bodies which are classed as ALBs:

1. Executive agencies act as extensions of their sponsor department. They generally do not offer policy advice, but focus on delivering specific services for the department. They have separate management from their sponsor department, but their chief executives are accountable to its ministers.

- Companies House is an executive agency of the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. It is responsible for incorporating and dissolving limited companies and registering their information so that it can be made available to the public.

- The UK Hydrographic Office is an executive agency of the Ministry of Defence. It collects and analyses information on the physical features of oceans and seabeds which is used by the Royal Navy.

2. Non-departmental public bodies (NDPBs) are not part of a government department and are more independent from ministerial control than executive agencies. NDPBs are split into executive NDPBs (which deliver services on behalf of government), advisory NDPBs (which offer independent advice to government) and tribunal NDPBs (which make legal judgements). undefined Cabinet Office, ‘Classification Of Public Bodies: Guidance For Departments’, Gov.uk, April 2016, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/519571/Classification-of-Public_Bodies-Guidance-for-Departments.pdf, p. 5.

- Sport England is an executive NDPB sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. It receives money from the government to promote sport within the UK, by investing in community sports groups and facilities and helping local authorities to develop sport in their areas.

- Other examples include: UK Research and Innovation, NHS England, and the Environment Agency.

3. Non-ministerial departments perform the same types of functions as normal government departments, although they tend to have more specialised remits. They do not have a dedicated minister because direct political oversight is deemed “unnecessary or inappropriate” for the matters they cover. However, as the IfG has shown, the extent of their independence from political oversight is varied and they include a wide variety of bodies.

- The Crown Prosecution Service is an independent body responsible for prosecuting criminal cases in England and Wales that follow investigations by the police or other investigative organisations.

- The Food Standards Agency works with local authorities to ensure that companies which make, prepare and sell food do so in a safe way. It also oversees labelling policy in the devolved nations.

Other public bodies are not classed as ALBs. This includes public corporations, which are organisations with significant commercial operations that maintain “substantial day to day operating independence” while being under government ownership. They include media organisations such as the BBC and Channel 4, regulators such as the Civil Aviation Authority, and other specialist bodies such as the Ordnance Survey.

In addition to these main categories there are several bodies that fall into older classifications such as ‘special health authorities’ like NHS Blood and Transplant. There are also various bodies that defy easy categorisation, such as the Crown Estate and the Bank of England. The persistence of the categories illustrates the complex nature of the work done by many public bodies, and the variety of relationships they have with ministerial departments. There are also public bodies associated with local government, such as Transport for London, and others supporting the devolved administrations.

Lastly, there are a small number of parliamentary bodies. These are not part of the government, are usually established by legislation, and typically have a separate legal personality and funding directly provided by parliament. These include organisations such as the National Audit Office, the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman and the Electoral Commission.

The number and complex taxonomy of these bodies has led governments to focus on NDPBs in previous waves of public bodies reform.

How many public bodies are there?

There are currently just under 300 ALBs, and a larger number of other public bodies. The government does not keep a comprehensive list of all public bodies, but the Office for National Statistics releases a regular dataset of public institutions. This lists 511 central government bodies (excluding ministerial departments and public bodies reporting to the devolved governments) and a further 292 public financial corporations.

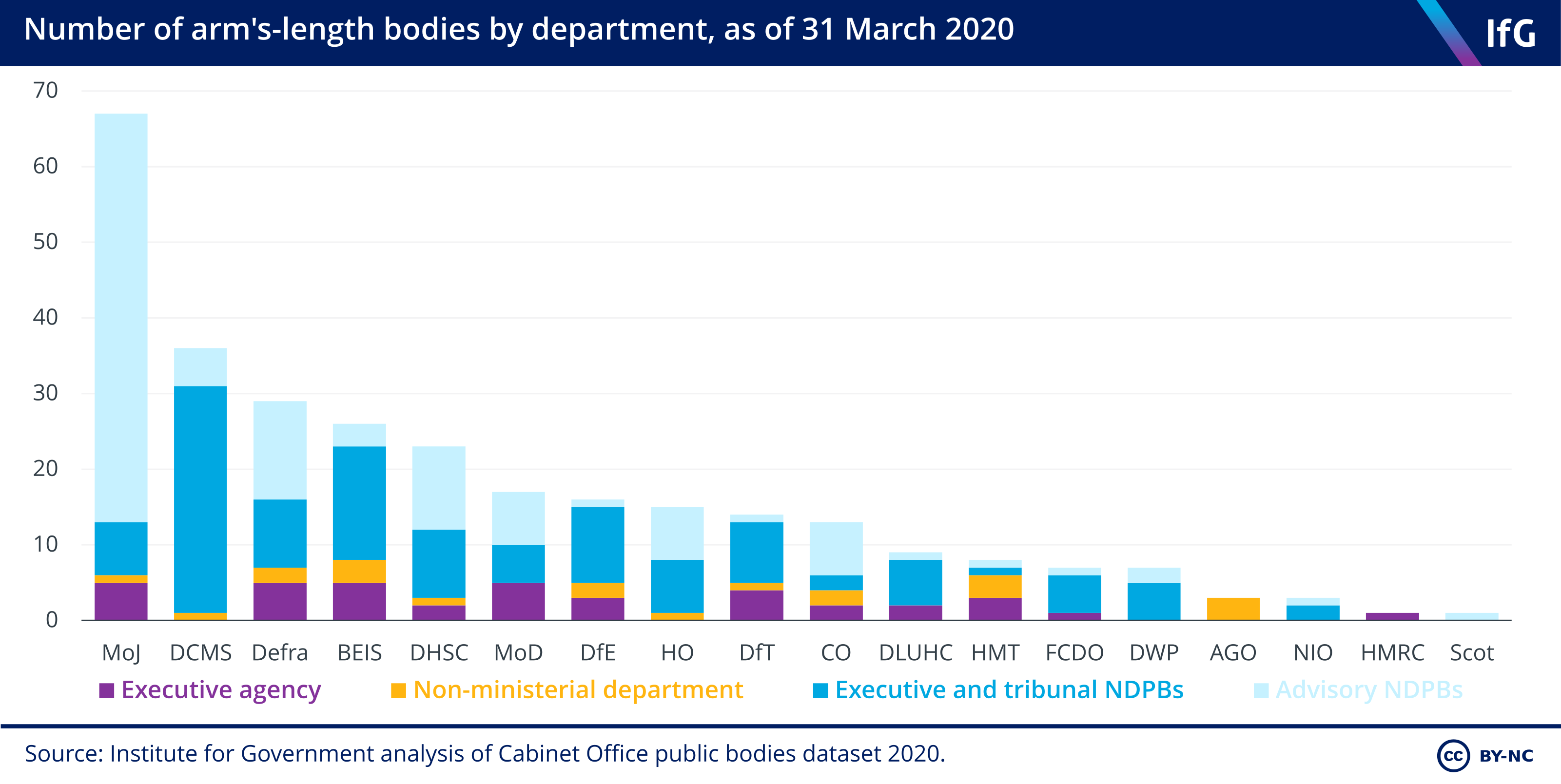

This chart shows that the majority of ALBs are NDPBs, with far fewer non-ministerial departments and executive agencies. But the sheer number of ALBs can be misleading as they vary significantly in size. For instance, the Ministry of Justice has the most, but most are local advisory committees on justices of the peace, which cost the government little and have small staff numbers. Additionally, although there are fewer of them, executive agencies spend more on average than other bodies, as they are often delivering major services. 10 Tribunal NDPBs are legacy bodies: all new tribunal functions must now be established within HM Courts and Tribunals Service, an executive agency. Cabinet Office, ‘Classification Of Public Bodies: Guidance For Departments’, pp. 12-13.

How big are public bodies?

While most public bodies are relatively small organisations, there are some which dwarf their sponsor departments – either in terms of staff numbers or budgets. For example the Department of Health and Social Care as a department only has 4,110 staff (full-time equivalent) but it delivers services through NHS England, which has a staff of 6,398. 11 For more detail on spending, staffing and accountability of arms-length bodies, see the ALBs chapter of Whitehall Monitor 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/whitehall-monitor-2022 NHS England conducts some specialist services itself, but in turn spends most of its income funding local NHS bodies, which manage most frontline health services and employ most health workers.

Three bodies – NHS England, the Education and Skills Funding Agency (ESFA, which funds schools and apprenticeships) and HMRC (which distributes child benefits and tax credits) – account for around 80% of all spending by ALBs. 12 ONS, public sector employment, September 2021 (DHSC core department), www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/publicsectorpersonnel/datasets/publicsectoremploymentreferencetable; Cabinet Office, public bodies dataset 2020, www.gov.uk/government/publications/public-bodies-2020.

- Topic

- Public bodies

- Keywords

- Arm's-length bodies

- Publisher

- Institute for Government