Gender balance in politics

This explainer takes a closer look at how women are represented in parliament, cabinet, the civil service and among ministers and special advisers.

Parliament is a body that exists to represent the entire UK population. More diversity in parliament, including more women MPs, brings a wider diversity of views and makes parliament more representative of the population it serves.

This is also true of government. If women are underrepresented, be it in the cabinet, parliament, the civil service, or among special advisers, it suggests that the potential pool of talent is not being fully drawn upon and valuable perspectives will be absent from decision making.

Yet, while progress has been made across government and parliament in the last decade, women remain underrepresented in both Houses of Parliament, the cabinet, the senior civil service and among ministers and special advisers.

Gender balance in parliament

What is the current gender balance in parliament?

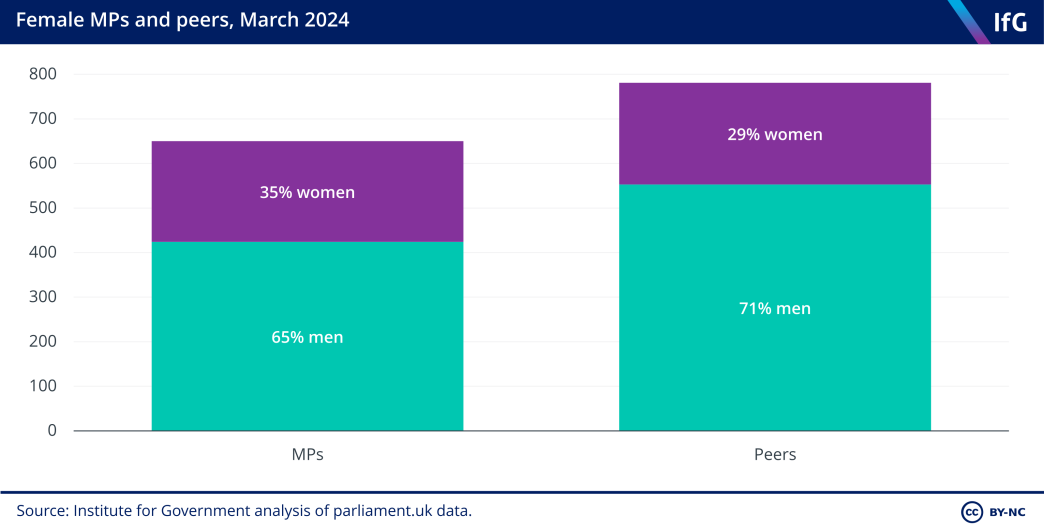

At the 2019 general election, 220 women (of a total of 650 MPs) were elected to the House of Commons – the highest ever proportion of women MPs. Of the 140 MPs elected for the first time in 2019, 57 (41%) were women. As of March 2024, there are 226 women MPs.

The House of Lords has 228 female peers, but they represent a smaller proportion – 29% – of the house (781 sitting peers).

How does the gender balance in parliament vary by party?

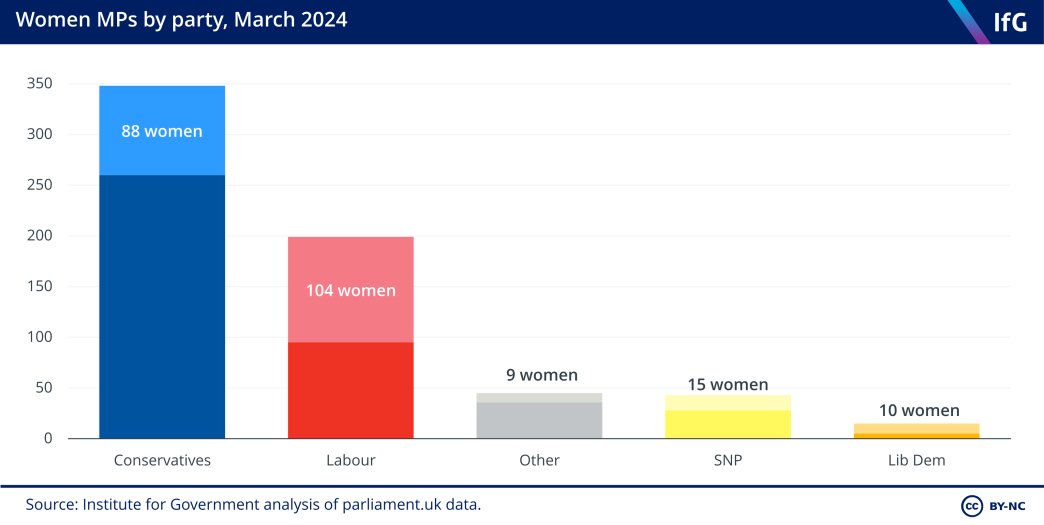

While more than half of MPs belong to the Conservative Party, fewer than 40% of female MPs are Conservatives. Of the four largest parties in parliament, the Conservatives have the lowest proportion of women MPs, at just 25%.

Around half (52%) of Labour MPs are women, as are two-thirds of Liberal Democrat MPs. The Green Party’s sole MP, Caroline Lucas, is a woman.

How has the gender balance in parliament changed over time?

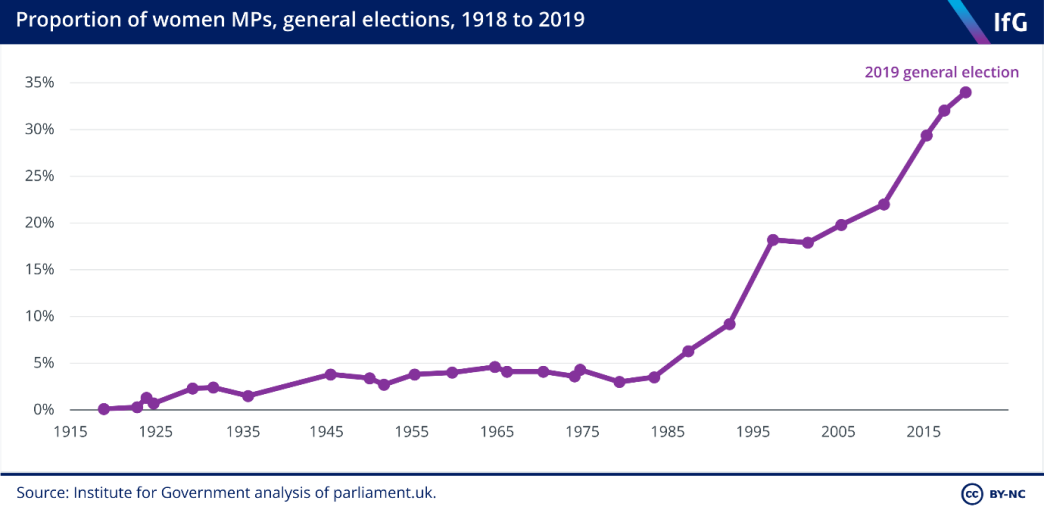

There has been steady increase over time in the House of Commons. Constance Markievicz was the first woman elected to parliament in 1918, but as a member of Sinn Féin, did not take her seat.

The first woman to sit in parliament was Nancy Astor, elected in 1919. It was not until 1987 that women exceeded 5% of MPs. Since then, the number of female MPs has grown rapidly, reaching 34% after the 2019 general election. The largest jumps were at the 1997 election when the proportion of women MPs doubled from 9% to 18%, and at the 2015 election when it rose from 22% to 30%.

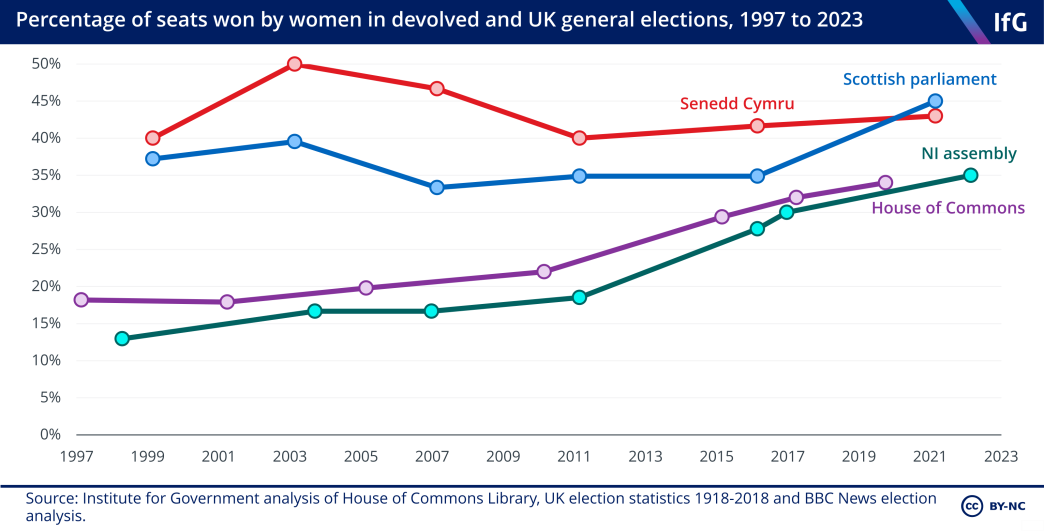

Across devolved governments there has been a more mixed pattern of growth. Since 1998, the number of women in the Northern Ireland assembly has increased from 13% to 35% of members. During the 2021 devolved elections, the Scottish parliament gained its highest ever proportion of women MSPs, with 45%. In Wales, the gender balance started at a higher level, but there has not been the same rate of progress. Senedd Cymru is the only legislative body in the UK that has ever had gender parity, when half of assembly members (AMs) elected in 2003 were women. Currently 43% of Senedd members are women. 11 Senedd Research, ‘Election 2021 How diverse is the Sixth Senedd?’, 11 May 2021, retrieved 19 December 2023, research.senedd.wales/research-articles/election-2021-how-diverse-is-the-sixth-senedd/

What is being done to achieve gender balance in parliament?

The election of more women to parliament is contingent on more women choosing to, and being selected to, run for parliament. While there are many factors that affect who decides to run and the barriers to becoming a candidate for MP, specific measures have been introduced to try and make parliament both more accessible and attractive to prospective women MPs.

One important development has been changes to the support given to MPs with caregiving responsibilities. For example, a pilot scheme was introduced in January 2019 to allow for proxy voting for MPs on parental leave, meaning that MPs who have new-born or newly adopted children can still participate in parliamentary votes. This reform has now been made permanent. In November 2019, Stella Creasy became the first MP to appoint a locum for her maternity cover. She has continued to campaign for MPs on parental leave to have all their duties in parliament covered during their absence, as is now the case for government ministers, according to the Ministerial and other Maternity Allowances Act 2021. Creasy has also supported more mothers entering politics via a campaign called This Mum Votes and has argued for mothers to be allowed to bring their babies into the House of Commons.

There have also been changes, in 2005 and 2012, to the House of Commons sitting hours. In the 1980s and 1990s, over 25% of sitting days would extend beyond midnight, but in the year following the 2017 election, this only happened three times. This makes working in parliament easier for those with caregiving responsibilities.

Some other countries employ electoral quotas to promote more female candidates in elections. These are easier to implement in nations with proportional representation systems. While this is not the case in the UK, political parties have been permitted to use shortlists comprised only of women in the selection of candidates for elections since the 2002 Sex Discrimination Act. So far only the Liberal Democrats and Labour have implemented this. However, other parties do have initiatives to encourage women to run for office, including the Conservatives’ Women to Win support network, which was launched in 2005.

How does the UK compare to other nations?

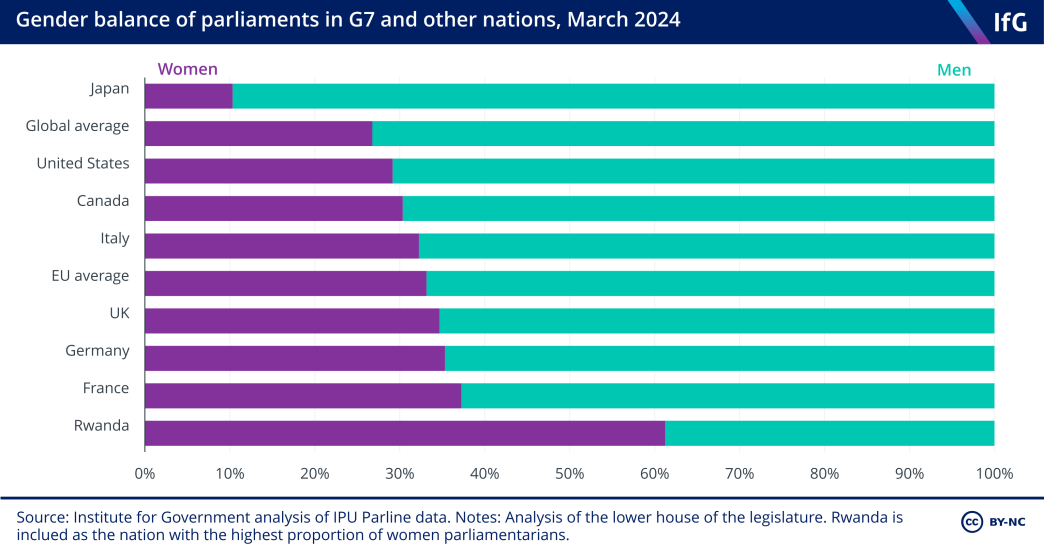

While the UK has some way to go to achieve gender parity in parliament, it does rank fairly well in comparison to other nations. The UK ranks 48th in the world for the proportion of women in parliament – 18th in Europe – and has the third highest proportion among G7 nations, behind France and Germany. Globally, just four nations, Rwanda, Cuba, Nicaragua and Mexico have female-majority parliaments.

In government, as of March 2024 the UK ranked 24th out of 38 OECD nations for the number of women in ministerial positions. 12 OECD, ‘Key charts on Governance’, OECD, 2019, retrieved 8 February 2022, www.oecd.org/gender/data/governance In contrast, it ranked 15th for the proportion of women in parliament.

Gender balance among ministers

What is the current gender balance among ministers?

There are currently 23 full members of the cabinet and nine other ministers who attend cabinet meetings. Of the full members of the cabinet, seven are women, as are three of the ministers who attend cabinet.

The women in cabinet are:

- Michelle Donelan, secretary of state for science, innovation and technology

- Victoria Atkins, health secretary

- Penny Mordaunt, leader of the House of Commons

- Kemi Badenoch, business secretary and minister for women and equalities

- Claire Coutinho, energy secretary

- Gillian Keegan, education secretary

- Lucy Frazer, secretary of state for culture, media and sport

- Laura Trott, chief secretary to the Treasury (attends cabinet)

- Victoria Prentis, attorney general (attends cabinet)

- Esther McVey, minister without portfolio (attends cabinet)

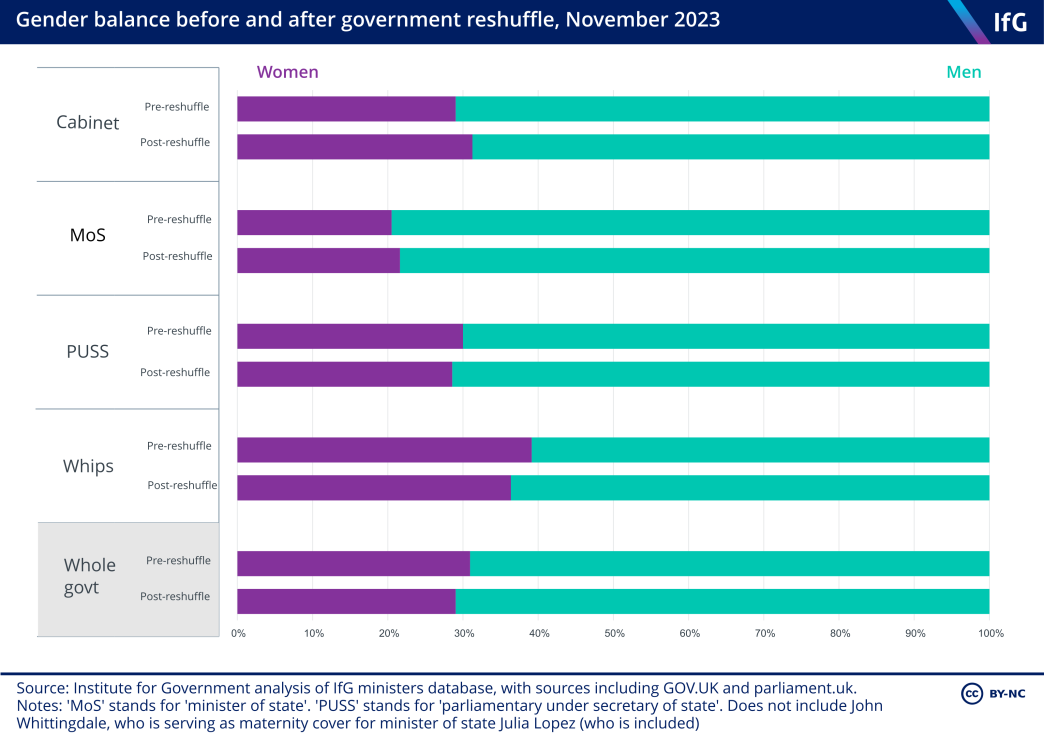

Rishi Sunak increased the proportion of women in cabinet in his November 2023 reshuffle, from 29% to 31%. However, the proportion of women in government as a whole fell, decreasing from 31% to 29%. All of the great offices of state are occupied by men. Every female minister was removed from the Department for Transport and the Ministry of Defence, and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs now has more ministers named ‘Robbie’ than female ministers.

Progress towards gender equality within government has never been uniform: the number of women at every level of government has fluctuated significantly over the past two decades. The proportion of women in Sunak’s cabinet is, for instance, lower than at the beginning of Liz Truss’ premiership, when it stood at 35%.

The representation of women is much higher among ministers in the devolved administrations. In Wales, women are the majority in both the cabinet (56%) and among ministers as a whole (64%). In Scotland, 60% of the cabinet is female and women represent 57% of all ministers.

How has the gender balance among ministers changed over time?

The first woman to become a cabinet minister was Margaret Bondfield, who served as minister for Labour between 1929 and 1931 during Ramsay Macdonald’s premiership. Tony Blair’s 1997 cabinet was the first to include more than two women simultaneously. 14 Watson C, Uberoi E, Mutebi N, Bolton P, Danechi S, Women in Politics and Public Life, 2 March 2021, commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn01250

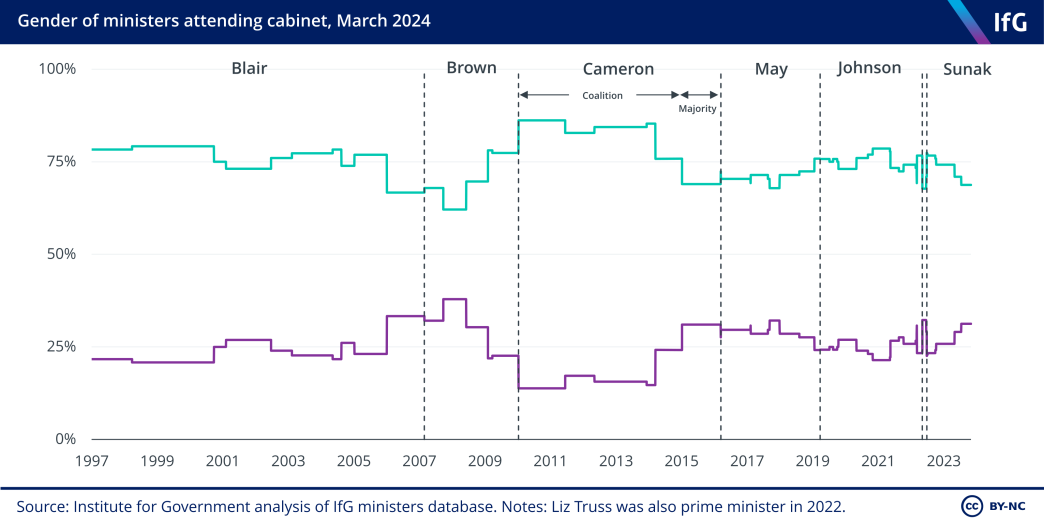

The cabinet has at no point reached gender parity. Its highest point was under Gordon Brown when, in 2008, 10 of the 28 ministers (36%) attending cabinet were women. The lowest proportion since 1997 was early in the coalition government when just four of 28, or 14%, of cabinet attendees were women. With the exception of the coalition government, when the number was lower, the number of women in cabinet since 1997 has generally been between 20% and 35% of attendees.

Unlike with parliament there has not been steady progress toward gender parity among ministers. While most cabinet roles have been held at least once by a woman, the key position of chancellor of the exchequer has always been held by a man.

What is being done to achieve gender balance among ministers?

As ministers are appointed by the prime minister, it would be entirely possible for Rishi Sunak to achieve gender parity in his cabinet. However, a relatively low proportion of Conservative MPs are women (currently 25%).

One important development in increasing the number of female ministers was the introduction of the Ministerial and other Maternity Allowances Act 2021. This was designed to allow the attorney general Suella Braverman to take six months of paid maternity leave. During this period, another minister (Michael Ellis – previously the solicitor general) was appointed to cover her functions and responsibilities.

Former female ministers have spoken about the prejudices they have faced in the role. Jacqui Smith, the first woman to be home secretary, reflected that after the 7/7 terrorist attack in London, “The thing that people most often said to me about my public performance that weekend was ‘You appeared… you seemed very calm and reassuring.’ Now there is a certain subtext there, which is ‘You were the first female home secretary and […] we partly thought you would go in, there would be a terror attack and you’d come out shouting ‘I can’t manage it, bring a man in’.” Since Smith’s tenure, half of the subsequent eight home secretaries have been women.

Margaret Beckett, the first, and until September 2021 the only, woman foreign secretary, also felt that she experienced discrimination in her role: “I remember one of the women, a fairly senior woman, saying to me, ‘You do realise that there are people in the Foreign Office who don’t think a woman should be foreign secretary?’ Which at that stage in the day would never have occurred to me.”

Jo Swinson, who served as women and equalities minister during the coalition, spoke of the importance of representation and role models: “It’s not as if you can’t have a male role model, but it is just easier as a woman to look at other women. And, of course, there are not that many women minsters.”

Gender balance among special advisers

What is the gender balance among special advisers?

As of March 2023, the last date for which data is available, there were 117 special advisers across government. Of that number, 45 were women and 75 were men. 16 Cabinet Office, ‘Annual Report on Special Advisers 2023’, 20 July 2023, assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/64e36fba3309b700121c9bc1/2023-06-20_-_SpAd_Annual_Report_2023_v3.docx.pdf

How has the gender balance among special advisers changed over time?

Special advisers are appointed by cabinet ministers and approved by the prime minister, but there is no uniform process for how they get the job. As a result, there is not a clear pipeline for becoming a special adviser.

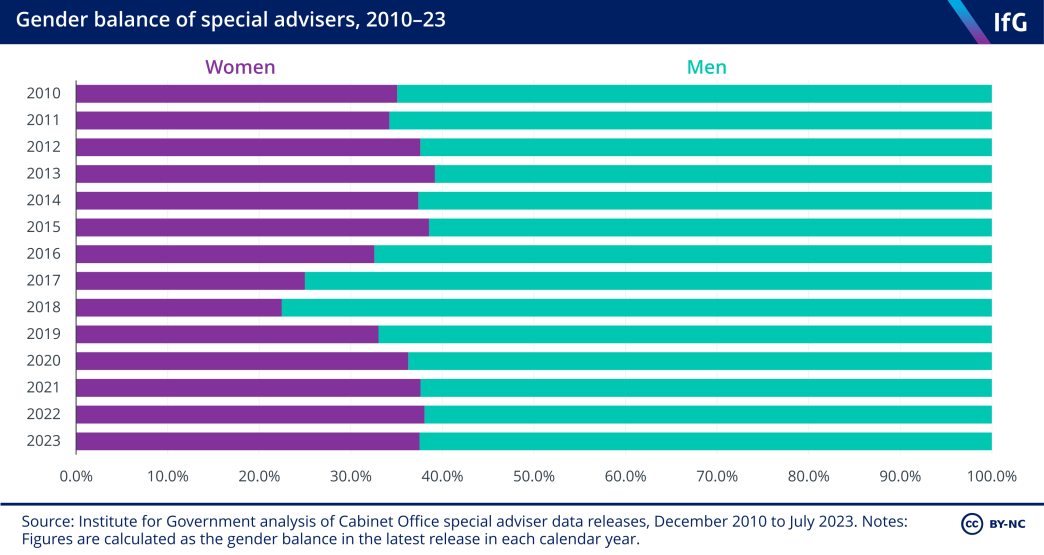

The gender balance of special advisers has varied year by year since 2010 between a high of 39% in 2013, 2015 and 2021 and a low of 22% in 2018. Boris Johnson’s government had, on average, more female special advisers than that of his predecessor, Theresa May.

What is being done to achieve gender balance among special advisers?

The government has not published any plan for improving the gender balance among special advisers, nor commented on the current imbalance. This may be because special advisers are generally less visible to the public, and so there is reduced public pressure on gender balance.

Given the close relationship between ministers and their advisers, it is difficult to take a cross-government approach to improving the gender balance. While appointments must be approved by the prime minister, each special adviser is personally appointed by the minister for which they work. Nonetheless, unlike ministerial appointments – which are influenced by the gender balance within parliament itself – special advisers are not appointed from a restricted pool of candidates, meaning that individual ministers could more easily ensure gender balance among their advisers.

- Keywords

- Cabinet Civil servants Government reshuffle

- Publisher

- Institute for Government