Funding infrastructure

How is infrastructure funded in the UK?

What do we mean by 'funding' infrastructure?

Funding is how you pay for infrastructure. That means over its lifetime, not just the upfront cash.

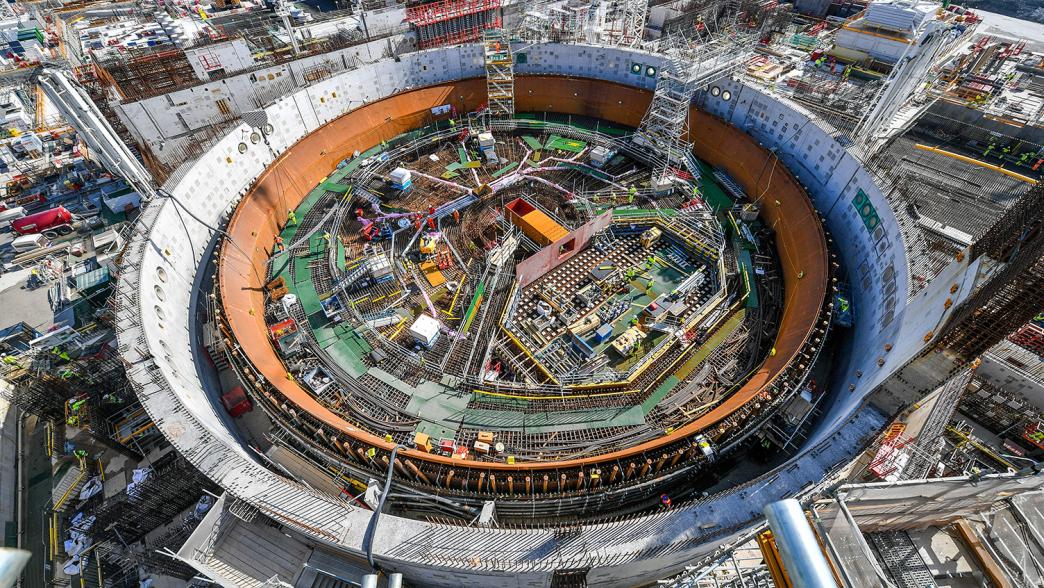

For example, Hinkley Point C will be paid for by energy consumers through charges on their bills, although foreign investors are paying for it to be built. High Speed 2 will ultimately be paid for out of taxes, even if government must borrow to cover the cost of construction.

Is there a difference between 'funding' and 'financing'?

Financing is how you meet the upfront costs of building the infrastructure, funding is how you pay for it over its lifecycle.

These terms are regularly used interchangeably, not only by journalists and analysts but by politicians too. But they are distinct.

Understanding the distinction is key to understanding where the problem lies in paying for infrastructure. The ability to finance a project is closely linked to funding.

Why does funding require more attention?

Without a clear funding stream, it can be difficult to access the upfront cash needed to construct new infrastructure. Governments are unlikely to finance a project if they do not believe that long-term maintenance and operation costs can be met.

The funding available to a project becomes ever more critical if private finance is sought to meet the upfront costs of building the infrastructure.

Evidence suggests there is no shortage of private finance seeking to invest in UK infrastructure. The bigger problem is a lack of clarity on funding which makes it difficult for investors to know how they will be paid back.

By having clear arrangements for funding, it is possible to unlock more investment which contributes to new infrastructure being built - and faster.

Where does the money to fund infrastructure projects come from?

The most common ways of funding infrastructure are either via taxes or charges.

- Taxes: funding for infrastructure - from A-roads to HS2 - comes out of government revenue. Around 60% of government revenue comes from income tax, National Insurance contributions and VAT.

- Charges: users can pay for use of assets, or the goods these assets generate, through charges. Utilities and related major projects are almost entirely funded this way in the UK. For instance, the Thames Tideway Tunnel will be funded by Thames Water customers. In other countries, charges have been used more frequently and in a wider variety of sectors, such as for roads in Norway and the Netherlands.

A third option is to capture rents or ‘windfall gains’ from infrastructure. This is based on the theory that infrastructure investment brings with it economic value, most commonly by increasing the value of the surrounding land. Currently, landowners keep all the benefit of an increase in their property value.

Measures such as a tax on the expected increase in property value resulting from an infrastructure project can allow the public sector to access this value and use it to pay for infrastructure. This funding method has been used in Milton Keynes to fund local infrastructure. In London, the Business Rate Supplement helped fund Crossrail.

There are other possible funding models, but they are much less common. For instance, seeking funding from the private sector or philanthropic sponsors (as proposed for the now cancelled Garden Bridge) is possible, but rarely used.

How does the UK currently fund infrastructure projects?

Taxes and charges account for almost all funding for economic infrastructure in the National Infrastructure and Construction Pipeline, which shows planned government projects.

Some projects use a combination of methods. For instance, the Barking Riverside extension to the London Overground is being funded through a mix of taxation, user charges and contributions from housing developers.

Are some infrastructure funding options better than others?

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to funding infrastructure. Some options may be more appropriate for certain projects and sectors than others. There are also a host of political considerations that may lead to some options being preferred.

The table below outlines the advantages and disadvantages of each funding model.

Option |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Taxation |

Straightforward: no additional costs to Government for collecting taxes. Size: even with squeezed government budgets and competition, there is a large potential amount of funds available compared to other funding sources. Equity: Some infrastructure may be considered a public good, e.g. water, flood defences. Some argue this means it should be publicly funded from taxes. |

Predictability: with limited budgets and a reluctance to raise additional taxes, projects must compete against other spending priorities. There is a risk that funding may be withdrawn and redirected to a new priority. Equity: some object to their taxes being used to fund localised infrastructure projects that will not benefit everyone. This has been a source of criticism for HS2. |

| User charges |

Predictability: future revenues are more or less guaranteed. This can help to secure financing for otherwise risky projects, as the Financial Times has argued was the case with Hinkley. Equity: those who use pay, and user charging is not necessarily more regressive than other forms of taxation. |

Size: charges can only be so expensive, before customers either cannot or will not pay. The National Audit Office has warned of household bills increasing so much that low-income households might not be able to pay. Equity: there are concerns that those with lower incomes will end up paying a higher proportion of their incomes on charges. High charges can result in public opposition – as anger at energy prices illustrates. Politics: user charges are not currently politically viable for many projects in the UK. Politicians have been reluctant to introduce more road pricing, despite the success of the London congestion charge. |

| Capturing rents |

Equity: those who benefit from the new infrastructure pay for it. The amount government derives from these groups is proportional to the benefit they gain. Size: some are optimistic that it could fund more projects and ‘unlock’ financing. |

Size: mechanisms have so far rarely been large enough to fund a project alone. Appropriateness: not all regional bodies have the power to charge business levies; not all types of infrastructure generate gains to the same extent; gains will be higher in urban and wealthier areas. Complex: value uplifts work differently in almost every case so developing a generic arrangement is hard, but bespoke arrangements are expensive. |

- Topic

- Policy making Public finances

- Keywords

- Infrastructure

- Publisher

- Institute for Government