The deputy prime minister and first secretary of state

What is the role of the deputy prime minister and the first secretary of state? And how do they differ?

Who is the deputy prime minister?

British prime ministers do not appoint a deputy equivalent to the US vice president. There is no deputy who would automatically take over if the prime minister were incapacitated, or who automatically deputises for the prime minister in their role.

However, UK prime ministers have sometimes given the title of ‘deputy prime minister’ to one of their cabinet colleagues and have sometimes asked a close ally to act as their informal deputy. The title of deputy prime minister and the role of acting as a de facto deputy to the prime minister can sometimes go together, but not always.

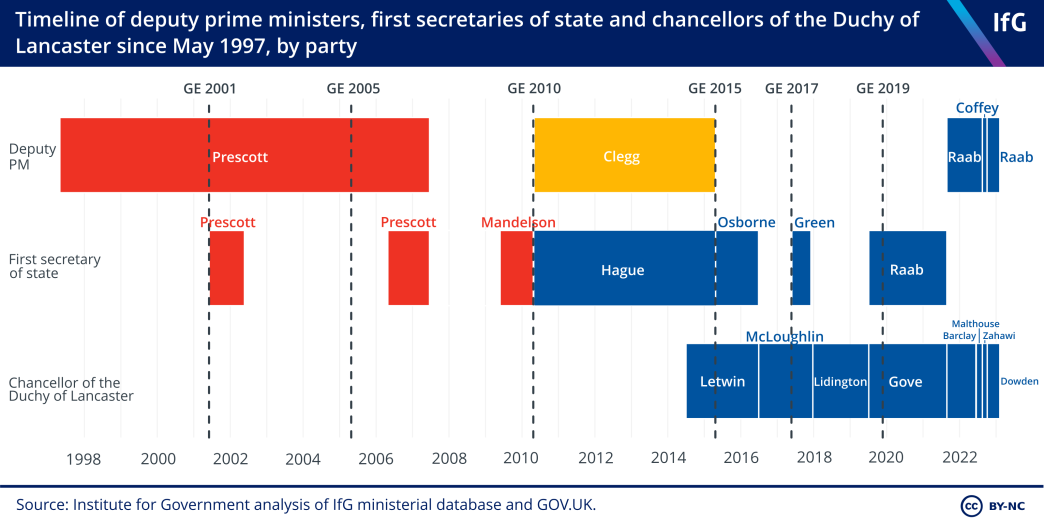

In recent years, the role of acting as a de facto deputy to the prime minister has sometimes held the title of deputy prime minister, but at other times been given the title of first secretary of state or chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (CDL).

Dominic Raab resigned as deputy prime minister and secretary of state for justice on 21 April 2023, after an investigation by Adam Tolley KC into allegations of bullying. He held this role from September 2021 to September 2022, and from October 2022 to April 2023. He also previously served as first secretary of state. Oliver Dowden was given the title deputy prime minister alongside his role as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

What is the difference between deputy prime minister and first secretary of state?

Both titles are used to confer status on the holder, but both can be purely symbolic. Neither title confers any automatic or constitutional powers.

The first secretary of state title formally means that the holder ranks below the prime minister but is more senior than other secretaries of state. It confers no automatic rights or responsibilities and can, though not always, coincide with a role deputising for the prime minister.

The title indicates where they might sit at the cabinet table, as the seniority of all cabinet ministers determines where they sit in relation to the prime minister. The chancellor usually sits beside the prime minister, on the other side from the cabinet secretary, with the next most senior cabinet ministers sitting directly opposite the prime minister. Less senior cabinet ministers sit at either end of the cabinet table (with those ministers who ‘attend cabinet’ sitting at a smaller table at one end).

There can also be a second or third secretary of state, but usually this informal rank is inferred from their position in the cabinet hierarchy rather than a title provided to them.

The title of deputy prime minister similarly confers no automatic rights and responsibilities. Its use has usually been either to give a title to the leader of a party in coalition with the prime minister’s party (Clement Attlee held the title during WW2 and Nick Clegg held the title during the 2010-15 coalition government). But the title is also sometimes used to convey a seniority above first secretary of state, either because a prime minister wishes to convey that a particular minister is being empowered or, more usually, because a particular minister has insisted on the title. It can sometimes be combined with a role deputising for the prime minister – in PMQs, cabinet committees or elsewhere, but not always.

How do other ministers deputise for the prime minister?

Unlike in the US, there are no formal rules for what to do if a prime minister is ill or incapacitated. Another cabinet member would usually be expected to take on some of the PM’s responsibilities. In 2020, when then-prime minister Boris Johnson went into intensive care while suffering from Covid-19 in April 2020, it was then-first secretary of state Dominic Raab who took on his day-to-day responsibilities. 17 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-52193461

When the prime minister is on holiday, a senior minister – which may or may not be the deputy prime minister or first secretary of state – is appointed to deal with day-to-day prime ministerial business.

If a prime minister is unable to take part in PMQs, because they are out of the country, attending other engagements, on leave, or ill, a senior minister similarly typically takes their place. During Boris Johnson and Rishi Sunak’s premierships, Dominic Raab frequently performed this duty as first secretary of state or deputy PM, but there is no requirement that the prime minister choose either of those office-holders to deputise at PMQs.

Sometimes, deputy prime ministers and first secretaries of state chair cabinet committees that are not chaired by the prime minister: Thérèse Coffey chaired two during her brief tenure as deputy PM in 2022, while John Prescott chaired nine cabinet committees in 2006. 18 https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN04023/SN04023.pdf

Currently, two cabinet committees were already being chaired by the CDL, Oliver Dowden, before he became deputy prime minister. None were chaired by Dominic Raab while he was deputy prime minister under Sunak. A prime minister might also use a close ally to act as a de facto deputy or ‘fixer’, and delegate aspects of the prime minister’s role to them. This might include chasing progress on key policies and, particularly, cross-cutting issues, brokering deals between departments and chairing meetings and committees. In recent years this role has been given to a minister based in the Cabinet Office, and therefore benefitting from the resources of the Cabinet Office and proximity to No10. Dowden was already believed to be undertaking such a role before he replaced Raab as DPM.

If a prime minister died in office, would the deputy prime minister take over?

Not necessarily. The UK has no automatic process for what happens if a prime minister dies or is incapacitated in office, although there are certain constitutional principles that would be followed. After Boris Johnson was hospitalised in 2020, the Cabinet Office considered what would be recommended practice in future, but this still does not amount to a constitutional rule.

The central constitutional principle is that a prime minister must be appointed by the monarch on the basis of commanding the confidence of parliament. There is no constitutional provision for an ‘acting prime minister’. The UK is formally governed by the cabinet who either exercise statutory and some prerogative powers in their own right, or who advise the monarch on how to exercise other executive powers. If the prime minister is incapacitated temporarily then the cabinet can advise the monarch in the absence of the prime minster.

A prime minister remains in post until they resign or otherwise vacate the role. In these circumstances, if the party in government had a majority in parliament then the requirement to command confidence would mean that the governing party would have to select a candidate with the support of its MPs. In practice, given that cabinet ministers are already acting as the monarch’s principal advisers, a replacement would likely be chosen by and from the existing cabinet, at least until a new leader of the party could be elected. This may be the PM’s deputy, but this is not guaranteed. 21 https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/article/comment/uk-now-needs-formal-acting-prime-minister-role 22 https://www.qmul.ac.uk/mei/news-and-opinion/items/what-happens-if-a-prime-minister-dies-in-office-dr-robert-saunders.html

Is there always a deputy prime minister?

No. The concept of a deputy prime minister is a relatively new phenomenon. The first deputy prime minister was Clement Attlee, who served during the wartime coalition from 1940-45. Between 1945 and 2010, eight ministers served as the PM’s deputy, but there were long periods without any deputy. 25 https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN04023/SN04023.pdf Since the appointment of Nick Clegg as deputy prime minister during the coalition, however, the title’s use has become more common – there have been three deputy prime ministers and three first secretaries of state since 2015. This excludes Philip Hammond who, in 2016, was mistakenly appointed to the role. 26 https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/hammond-promoted-to-pm-s-deputy-by-mistake-v2d978vqb There have been two periods since 2015 with no appointed deputy prime minister or first secretary of state (though, for some of that time, the CDL performed a similar role).

Lord Mandelson, who served as Gordon Brown’s first secretary of state from 2008-10, described the distinction to the IfG’s Ministers Reflect archive:

“Gordon [Brown] wanted to name me as Deputy Prime Minister but First Secretary was inserted instead because I was in the Lords rather than the Commons. It didn’t matter to me and I tried to do a job.”

Sometimes there is both a deputy prime minister and a first secretary of state in one government: this was the case during the coalition, when William Hague was first secretary of state and Nick Clegg was deputy prime minister. This was because Clegg filled the role of deputy PM as the leader of the junior coalition party, rather than as a party ally of the prime minister. Unlike Hague, Clegg attended the ‘quad’ of ministers who were involved in day-to-day resolution of any coalition decision making issues. Occasionally, the same person has held both titles at once – John (now Lord) Prescott held both from 2001-2 and from 2006-7. Sometimes, there is neither a deputy prime minister nor a first secretary of state. For example, when Damian Green was sacked as first secretary of state in 2017, David Lidington became Theresa May’s de facto deputy as CDL.

Is there a department of the deputy prime minister?

No – the title of deputy prime minister or first secretary of state has usually been held by someone with another cabinet position. In 2010, Clegg operated as DPM from the Cabinet Office, and was given a beefed up office to support his duties. He was also lord president of the council, which is a separate title that conveys seniority but which also comes with responsibility for the privy council. Damian Green held the title of first secretary of state alongside that of minister for the cabinet office.

Some deputy prime ministers have had a formal office within the Cabinet Office. In 2001, for example, Tony Blair created an Office of the Deputy Prime Minister within the Cabinet Office, where John Prescott held responsibility for policy areas including the Social Exclusion Unit and Regional Coordination Unit, alongside his department responsibilities for Environment, Transport and the Regions. 28 https://web.archive.org/web/20060619223108/http://www.parliament.uk/commons/lib/research/notes/snpc-04023.pdf The Cabinet Office responsibilities were later removed in the 2006 reshuffle. As Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, Dowden is also the most senior minister in the Cabinet Office.

As the role of deputy PM or first secretary of state is often held in conjunction with another cabinet post, it is usually unpaid. Dominic Raab, for example, was both deputy prime minister and justice secretary, while his predecessor, Thérèse Coffey, was both deputy prime minister and health secretary.

How important is the role?

This depends on the circumstances of government. During the coalition, the deputy prime minister was unusually powerful because Nick Clegg was the most senior representative of the Liberal Democrats in government. His position was written into the coalition agreement, and some responsibilities were transferred from the secretary of state for justice to the deputy PM to increase his powers. He told our Ministers Reflect archive:

“I know the title was the same, but my role [as deputy prime minister] bore absolutely no relationship to John Prescott or Michael Heseltine. Because it was just a very brutal symmetry. The Coalition Government couldn’t do anything unless both sides agreed. So we had to set up from scratch something which Whitehall has never done before, and certainly has not done since, which is create a sort of two-headed, bicephalous way of making decisions.”

Outside of coalition, the relative strength of the deputy prime minister or first secretary of state depends on their relationship with the prime minister. As first secretaries of state Lord Mandelson and Damian Green were, in particular, known for acting as fixers for the prime minister, as was David Lidington as Theresa May’s Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Other prime ministers have relied on their chancellor as a second in command.

- Keywords

- Cabinet

- Public figures

- Dominic Raab Nick Clegg

- Publisher

- Institute for Government