Sunak, Starmer and the IfG agree: we need change at the general election

A return to stability would mean a transformational change to the way government works.

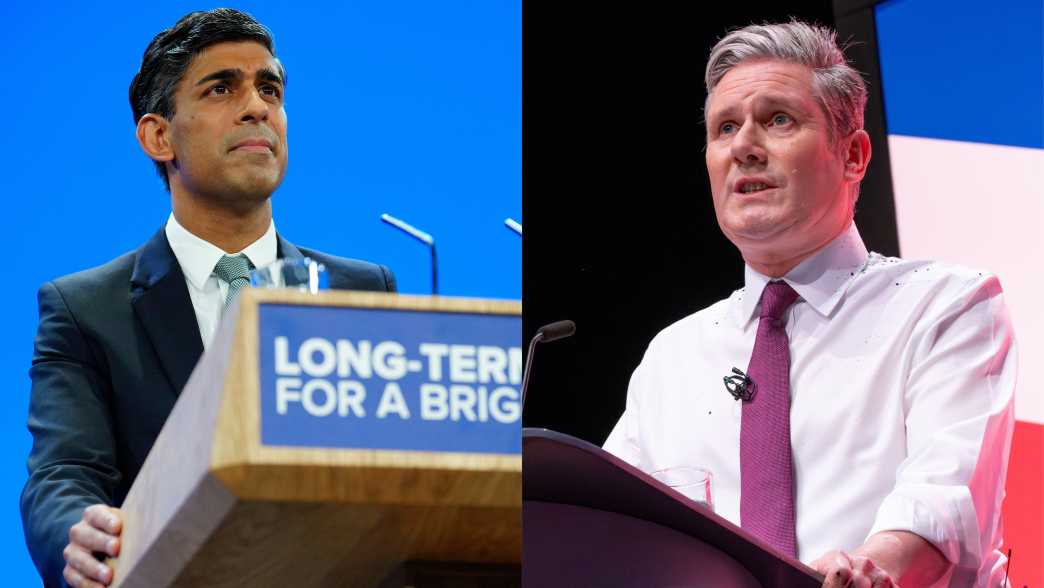

As the general election looms closer both Rishi Sunak and Keir Starmer are pitching to be the candidate of change – and, says Joe Owen, both are entirely right to want to do things differently

Rishi Sunak has called for an end to the ‘30-year political status-quo’. Keir Starmer wants to rid the UK of the ‘disease of sticking plaster politics’. Sunak wants to ‘change the direction of our country’. Starmer wants a ‘decade of national renewal’. There is a consensus in British politics: things are not working; the public have been poorly served; and change is sorely needed.

The two parties are developing their pitches for what that change should look like. Both will offer new policies and a new approach, with the promise that they are best equipped to turn around the fortunes of the UK. But in practice, the most transformational change to how government operates might be the most boring: a return to some sort of stability.

Neither party has yet set out its programme for change

The prime minister has just over a year to call the election that is promised to deliver change – the last possible polling day is 28 January 2025. The longer Sunak waits, the more likely it is that the the UK's economy is improving. If he waits too long, however, then he faces a campaign that runs over Christmas as well as accusations he is shying away from the electorate. The local and mayoral elections in May are either a threat or an opportunity for him, depending on which person's views you hear.

Sunak inherited a mess when he became prime minister. His immediate priorities were short term and about proving he could return the country to some immediate stability after Liz Truss’s premiership. But in the last few weeks, there has been a concerted effort to sketch out a wider agenda – one that focused on ‘long-term’ decisions.

The smoking ban and, if it becomes more than just a white paper, post-16 education reforms both fit that bill – and appear to be the result of Sunak’s personal convictions and priorities rather than focus groups. The higher-profile changes on HS2 and net zero targets seem as much to do with immediate pressures and short-term tactics. Scrapping HS2 may allow (with some creative spreadsheet work) space for pre-election tax cuts, while flexing some net zero targets opens up an attack line on Labour following the ULEZ-dominated Uxbridge by-election, albeit at the cost of frustration from industry.

If Sunak’s recent announcements have been driven by combination of conviction and opportunism, Starmer’s have been more about coherence, tidiness and setting a framework for his agenda, his manifesto and – if he is successful – his programme for government. Earlier this year, Labour set five national missions and a promise of a new approach to government. Those missions are starting to evolve, with concrete pledges supporting the (in some cases) fluffy ambition statements. In recent weeks, Labour has set out new commitments on housebuilding targets, teacher retention payments, and new public bodies. Starmer is also tweaking the missions to make them ‘bombproof'. There has been less talk of £28bn for green energy and less talk of Labour’s mission to achieve ‘fastest growth in the G7’, and instead a promise to unblock building. Like Sunak, Starmer will want to use the coming months to refine his promises and policies, but the opposition must juggle their desire for ambition with their strictly enforced fiscal strait jacket.

The biggest change either side could deliver is stability, not policy

Rather than detailed policy announcements, both leaders dedicated a significant proportion of their conference speeches to talking about the UK’s broken political system in the UK. They are right that it isn’t working.

For almost a decade, the UK government has rarely been able to think more than, or even close to, a year ahead. The 2015 election, Brexit referendum, Brexit itself, Covid, partygate, an energy crisis, war in Europe and economic instability – all dominated the time and energy of ministers, their advisers and civil servants throughout government. There have been four prime ministers in seven years. Ministerial turnover has hit record rates and policies have been dropped, replaced or changed with the arrival of new political leaders in departments.

Since George Osborne’s Treasury ran the 2015 spending review, only one chancellor has conducted a multi-year spending review – Rishi Sunak in 2021. The instability, particularly due to Brexit and Covid, has resulted in aborted attempts and a combination of roll-overs, top-ups and tweaks to budgets.

Since 2015, projects and programmes have often had little more than a year’s funding certainty, within which time there could be a new minister, secretary of state or prime minister: in some cases, all three. That environment makes it very difficult for departments, public services or private sector investors to make long-term decisions.

A prime minister with a majority, who can set out a plan for a parliament – built around a long-term vision for government – with a reasonable prospect of seeing it through, is potentially the most transformational change we could see after the next election. But it also is far from guaranteed: a hung parliament and the prospect of instability, new leaders and fresh elections remains a possibility.

There needs to be a change in how government works

Both the government and the official opposition say they want to change how government works. Starmer has promised a ‘mission-led’ government that works with the wider public and private sector to deliver. Sunak, who has been PM for less than a year, wants to make ‘long-term decisions for a brighter future’. Both promise to lead a government that is more interested in what it is going to do rather than what it is going to say.

The Institute for Government’s work has shown the damage that years of instability have wrought. Government can support the conditions for people to live the lives they want, work with industry and other parts of government to deliver on ambitious shared goals and build public services that work. But to do that, the way government functions needs to change. The Institute for Government will be publishing a series of recommendations for both parties over the coming months: ways they can deliver their ambition for a change in how government works and the horizons over which policy is made and delivered. We will recommend critical improvements on standards, policy making, the centre of government and spending reviews. If both parties are serious about improving the political system, they are right that change is sorely needed – whenever the next general election is held.

- Political party

- Conservative Labour

- Position

- Prime minister Leader of the opposition

- Administration

- Sunak government

- Department

- Number 10

- Project

- General election

- Public figures

- Rishi Sunak Keir Starmer

- Publisher

- Institute for Government