The government is right to rebalance funding towards disadvantaged councils

Stuart Hoddinott welcomes the new local government finance settlement's announcement that more money will go to disadvantaged councils.

While the autumn statement was relatively generous for all local authorities, Stuart Hoddinott welcomes the new local government finance settlement's announcement that more money will go to disadvantaged councils

Before the autumn statement, local authorities faced a perfect storm of financial pressure. Demand for services was increasing as the cost of providing those services was rising – all against the backdrop of expensive social care reforms due to come into effect in 2023. 18 Davies N, Hoddinott S, Fright M and others, ‘Neighbourhood services’ inPerformance Tracker 2022, 17 October 2022, retrieved 15 December 2022, https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/performance-tracker-2022/neighbourhood-services The autumn statement ameliorated some of those concerns, providing local authorities with new grant funding and the ability to raise more revenue from council taxes, but left unanswered the question of how the government would distribute that grant funding to the 333 local authorities in England. This week’s local government finance settlement 19 Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, Local government finance policy statement 2023-24 to 2024-25, 12 December 2022, retrieved 15 December 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/local-government-finance-policy-statement-2023-24-to-2024-25/local-government-finance-policy-statement-2023-24-to-… – the process by which the government allocates funding to local authorities for the next financial year – answered many of those questions.

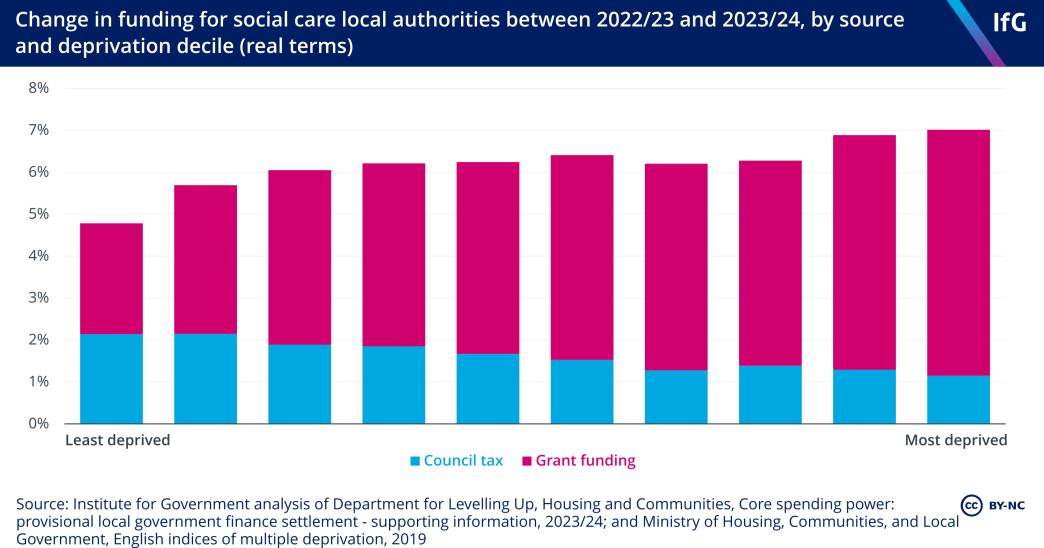

One of the major headlines in the autumn statement was that local authorities would be able to raise council tax by more in 2023/24 than in 2022/23 – by up to 5% for some authorities. But this was not good news for everyone. Better-off local authorities benefit more from council tax increases than their worse-off counterparts, raising the risk that the most deprived local authorities would lose out from the autumn statement announcement, as we pointed out at the time. In that context, councils have welcomed the announcement in this week’s finance settlement 20 Marchant C, ‘Local government settlement ‘better than sector feared’’, Room 151, 20 December 2022, retrieved 21 December 2022, www.room151.co.uk/funding/local-government-settlement-better-than-sector-feared/ that core spending power (CSP) – the amount of money available for local authorities to spend on social care and neighbourhood services, and which is made up of a combination of council tax and grant funding – will increase 5.8% in real terms, to £59.5 billion in 2023/24. Crucially, however, the government has used the finance settlement to direct more grant funding to the most deprived authorities. This effectively counterbalances the increases that less deprived authorities receive from increasing council tax and means the largest increases in CSP will go to the most disadvantaged local authorities, addressing the concerns we raised after the autumn statement.

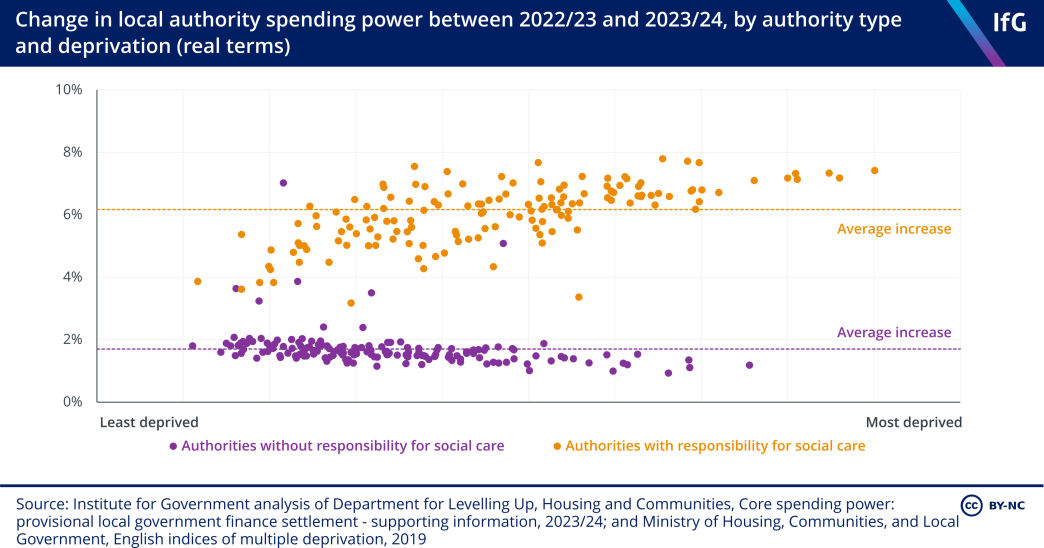

Another noticeable trend is that social care authorities – those with responsibility for delivering both adult and children’s social care – will see their CSP increase by more than non-social care authorities – 6.2% in real terms, compared to 1.7%. This is because social care was arguably the main cause of upper- and single-tier authorities’ financial pressure in the coming year, meaning funding will be directed towards a struggling service. To compensate lower-tier authorities for this, the government committed to a 3% minimum uplift in cash terms in 2023/24 – a promise that they fulfilled in this settlement.

While some local authorities will argue that this is not much money, the increase must be considered in the context of spending settlements for other services. Outside of health, adult social care, and schools, no other public service received any increase in funding in the autumn statement.

The settlement also addressed concerns about distribution and certainty of funding

The most deprived local authorities will see the largest increases in CSP, which the government achieved by allocating more grant funding to the most deprived authorities (see chart below). While this may seem common sense, there was no guarantee that this would happen after the autumn statement, and is counter to the trend of cutting grant funding most in the most deprived local authorities. 25 Atkins G and Hoddinott S, Neighbourhood Services Under Strain, Institute for Government, 29 April 2022, retrieved 15 December 2022, www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/neighbourhood-services

The finance settlement is the process by which the government allocates funding to local authorities for the following financial year. So their decisions in this year’s iteration should be welcomed for two reasons. First, the cost of living crisis will be felt most keenly by the residents in more deprived local authorities. This will mean that there will be both more demand for services and that it will be more difficult for authorities to raise council taxes. Second, the CSP rise begins to reverse some of the cuts of the 2010s.

It is also welcome that this is a multi-year settlement. We have previously highlighted the trend of government providing single-year finance settlements, but this is the first multi-year settlement since 2017 26 Local Government Association, ‘The 2018-19 Provisional Local Government Finance Settlement – Response’, press release, 15 January 2018, www.local.gov.uk/parliament/briefings-and-responses/2018-19-provisional-local-government-finance-settlement-response and will provide local authorities with more certainty over funding, hopefully encouraging more effective financial planning.

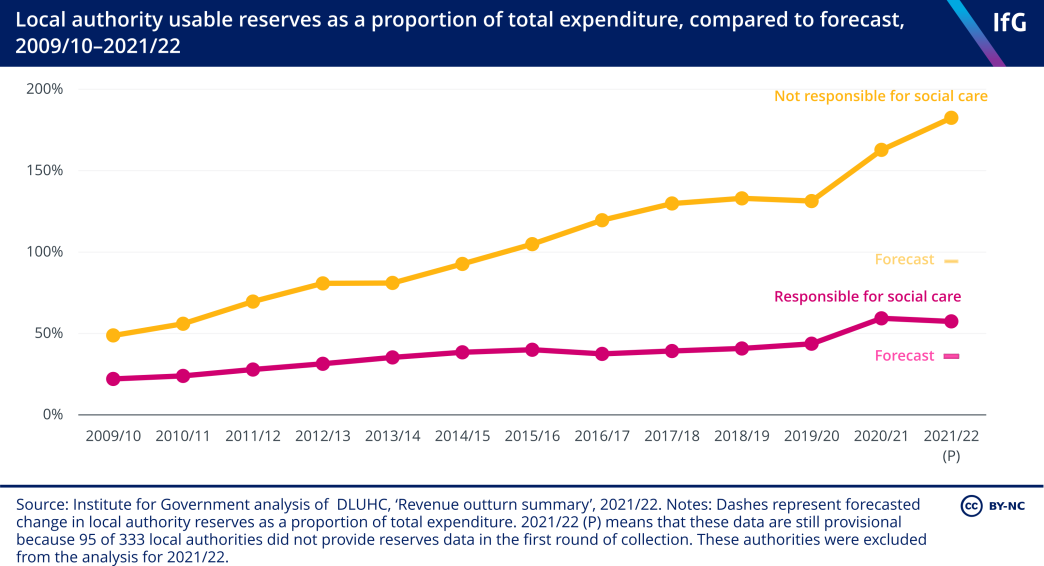

The government also made clear that it has noticed the trend of local authorities holding higher reserves – a phenomenon that we pointed out in this year’s Performance Tracker. The finance settlement warned that authorities should “consider how they can use their reserves to maintain services in the face of immediate inflationary pressures” and that it would start to effectively name and shame those authorities which continued to hold reserves while reducing service levels by publishing a “user-friendly” 27 Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, Local government finance policy statement 2023-24 to 2024-25, 12 December 2022, retrieved 15 December 2022, www.gov.uk/government/publications/local-government-finance-policy-statement-2023-24-to-2024-25/local-government-finance-policy-statement-2023-24-to-… version of the dataset, intended for use by the public to see how much their authority is holding in reserves.

In some ways this is fair: local authorities are supposed to draw on reserves during times of financial pressure, something which they have clearly not been doing. But it could also be argued that this is a rational response by local authorities, as they have faced a decade of cuts to their grant funding and uncertainty about their finances beyond the next financial year. There is therefore a dual benefit to multi-year funding settlements: they provide local authorities with more certainty, which in turn encourages them to use reserves.

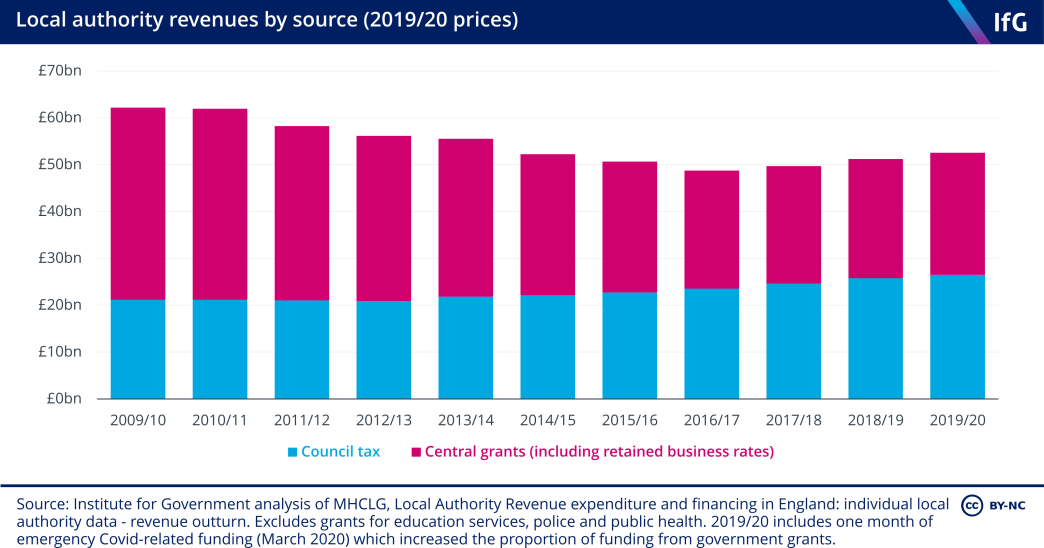

Local authorities are still worse off than in 2010

While this finance settlement should be welcomed, it is important to place it in a larger context. First, while the increase in CSP is relatively large it does not redress the depth or distribution of cuts that government made during the 2010s. Local authority funding fell by 15.5% in real terms between 2009/10 and 2019/20, with the majority of that driven by cuts to grant funding, which fell 36.5%. Those cuts also disproportionately affected more deprived authorities, who relied more heavily on that revenue source, as we showed in this report. This settlement redresses some of this, but does not full compensate authorities.

Second, the settlement also confirmed that the government has delayed the Fair Funding review – a consultation intended to reassess the relative needs of local authorities and therefore determine future funding allocations – again, this time until at least April 2025, 28 County Council Network, ‘Local government finance policy published: CCN response’, 12 December 2022, www.countycouncilsnetwork.org.uk/local-government-finance-policy-published-ccn-response/#:~:text=It%20also%20announced%20the%20government's,CCN a full nine years after it was first announced. This means that the government will continue to make funding allocation decisions based on the relative need of authorities in 2013/14, the last time the baseline was reset. This substantially disadvantages those local authorities whose need has become greater in the intervening years.

Finally, a substantial proportion – £1.4 billion, or 28% – of the increase in CSP comes from delaying implementation of adult social care charging reforms. Delaying this reform breaks one of the Conservative party’s key manifesto promises and will mean continued financial insecurity for those who rely on the service. It will also mean that implementation of the recommendations from the Dilnot commission will not take place until at least 14 years after they were first made.

So while this finance settlement is welcome and certainly a step in the right direction, it does not fix the parlous state of local government finance that has been caused by longer term and unequal cuts to grant funding and an unwillingness by the government to properly fund adult social care.

Thanks to Adrian Jenkins of Pixel Financial Management for sharing his analysis of the settlement

- Topic

- Public services

- Keywords

- Local government Economy Social care Budget

- United Kingdom

- England

- Publisher

- Institute for Government