Three steps for government and local leaders to make England’s devolution deals work

The lessons the government should learn from the last wave of devolution to city-regions.

With the government making steady progress on its goal of concluding devolution deals with all parts of England, Alex Nice sets out the lessons it should learn from the last wave of devolution to city-regions

Delivering on levelling up, an already ambitious agenda to address deep seated regional inequalities, looks to have become even more difficult. Amid a cost of living crisis, the autumn statement set out a new era of tight budgets for government departments However, levelling up is not just about giving out money, it is also about giving away power – and decentralising power need not mean higher spending.

When the levelling up white paper was published in February, we commended the government’s ambitions for further devolution as that document’s most radical set of proposals.

Since then, the government has made steady progress on at least one of its 12 levelling up ‘missions’: the goal to strengthen local leadership by concluding a devolution deal with all parts of England that want one by 2030. In the autumn statement, the chancellor announced that new devolution deals would soon be concluded with local authorities in Suffolk, Cornwall, Norfolk and the North East of England. This follows deals concluded with council leaders in North Yorkshire and the East Midlands in August this year. This is welcome, but the new arrangements will only succeed if proper time and resources are put in first.

Over half of England will soon have a directly elected mayor

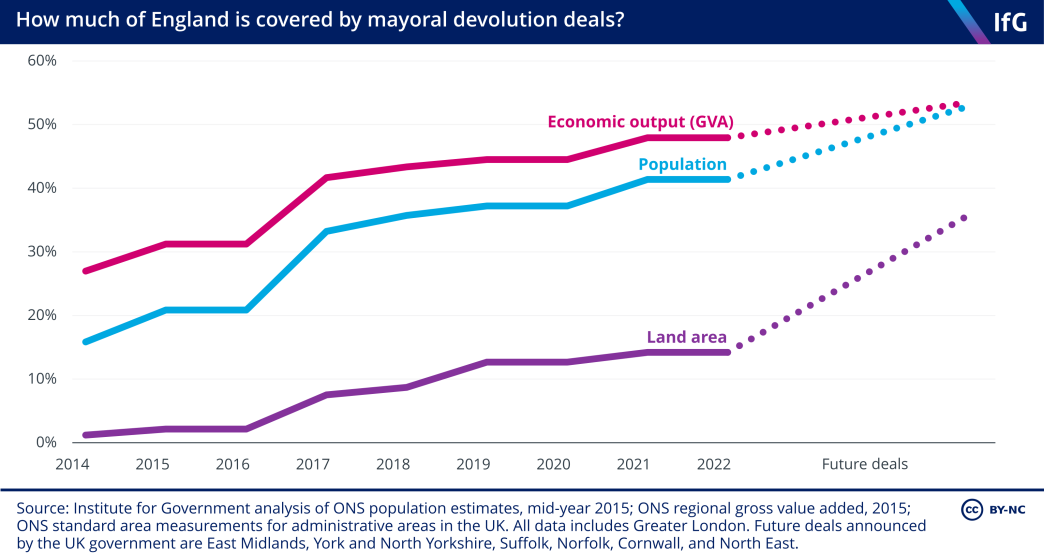

We are close to a tipping point in the governance of England, which has long been an outlier in not having a ‘middle tier’ of governance between Whitehall and local authorities. When these deals are concluded over 50% of the population of England will live in an area with a mayoral devolution deal.

It is not implausible that the government’s goal to establish devolved institutions in all parts of England by 2030 will be achieved. Many local leaders have misgivings about creating the position of a directly elected mayor. However, they also recognise that directly elected mayors have a bigger national platform, more regular access to UK ministers, and can more effectively advocate for their regions. And as more regions conclude devolution deals, those areas without mayors may increasingly start to worry they will be left behind.

Signing a devolution deal is just the first step of a long process

Once they are put into law, the new devolution deals will establish directly elected mayors and give the regions they lead a long-term funding settlement to support economic growth, along with new powers over transport, adult education, and planning.

However, concluding devolution deals is only the first step in the process. Where the devolution deal is with a single upper-tier local authority, such as in Norfolk, Suffolk, and Cornwall, councillors will have to adapt to working with a directly elected mayor who is likely to have a much bigger profile than the existing leadership.

Where the devolution deal creates a mayor-led combined authority involving several councils, such as in the East Midlands and North Yorkshire, success depends on establishing strong governance and effective institutions that encourage joint working. Since the first ‘metro mayors’ were elected in 2017, some mayoral combined authorities have made real progress in strengthening regional cooperation. Others have struggled. Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, for example, has recently had to appoint an independent improvement board chaired by Lord Kerslake, former head of the civil service, to address governance concerns.

The success of the new deals depends on effective implementation and local capacity building

Our research has identified a number of lessons that the UK government and local leaders should keep in mind as they put devolution deals into practice in their regions.

First, local authorities need to maintain close dialogue with each other and the government. Past experience has shown that devolution deals can fall apart at a late stage, even after the broad terms of the deal have been agreed with the UK government. For example, in 2016, draft deals with East Anglia and Greater Lincolnshire collapsed after some of the constituent local authorities decided to withdraw. In South Yorkshire, some of the powers agreed in 2015 were not transferred until 2020 because two of the constituent councils, Barnsley and Doncaster, initially sought to be part of a wider ‘One Yorkshire’ deal instead. Councils also need to consider how they will build local buy-in for the governance changes. Local residents will not be given a vote on the proposed governance reforms. But the new institutions will only become embedded if they are understood and seen as legitimate by local residents.

Second, local councillors and Whitehall officials should give themselves sufficient time to work through the institutional arrangements, particularly when forming a combined authority. In the past, rushing implementation has led to poorly drafted legislation. For example, in the West of England Combined Authority, the mayor cannot vote on the budget for the combined authority he leads. They must also ensure that there is an adequate scrutiny framework to hold the new mayors to account. The scrutiny arrangements in some mayoral combined authorities are widely acknowledged to be too weak. The government has recognised this, and is considering how to improve the accountability framework for mayors.

Finally, the UK government should ensure that the new mayors’ offices are adequately resourced, particularly when the new devolution deals involve creating a brand new combined authority with several local councils, as will be the case in the East Midlands and North Yorkshire. Setting up a combined authority is hard. The arrival of a high-profile mayor can lead to tensions with existing council leaders. Local authorities have to develop new ways of working together and these can often take several years to become embedded. Mayors need sufficient resources to navigate these challenges.

The government is making steady progress towards its goal of concluding devolution deals with all parts of England. To maintain support for the devolution agenda, and realise its goal of empowering local leaders to deliver levelling up, it needs to invest sufficient time and resources into the new structures.

- Supporting document

- metro-mayors.pdf (PDF, 1.4 MB)

- Topic

- Devolution

- Keywords

- Levelling up Economy Local government

- Publisher

- Institute for Government