How to devolve English government

Consensus is emerging about the case for English devolution, but the scale of the challenge needs to be addressed in central government.

That England needs a comprehensive and functional model of sub-national devolution is increasingly recognised on all sides of the political divide. A succession of Conservative governments have shown intent in this area, most recently with the ‘trailblazer devolution deals’ for the West Midlands and Greater Manchester in March. Meanwhile, the Labour Party’s Commission on the Future of the UK led by Gordon Brown culminated in a 2022 report that majored on the decentralisation of government in England. This emerging consensus has been noted and welcomed by a number of observers. 6 Williams J, ‘English devolution back on the political agenda’, Financial Times, 16 January 2023, www. ft.com/content/c91025d0-f6ce-4621-91bc-b0f5030eef73; Editorial, ‘The Guardian view on English devolution: an idea whose time has come’, The Guardian, 29 January 2023, www.theguardian.com/politics/ commentisfree/2023/jan/29/the-guardian-view-on-english-devolution-an-idea-whose-time-has-come; Payne S, ‘Tories must completely reimagine the state’, The Times, 3 March 2023, www.thetimes.co.uk/article/ tories-must-completely-reimagine-the-state-2gc62b0g9

The struggle for greater devolution in England is not new – or easy

Half a century ago, Harold Wilson spoke in the Commons to welcome the 1969 Redcliffe-Maude report on local government reform, arguing that it was “opening the way for more devolution in decision-making”. In subsequent decades, one reform plan after another has come and gone, each layering further complexity upon existing arrangements, and none completing the job that was attempted.

With forms of legislative devolution being established elsewhere in the UK at the end of the 1990s, England has become an anomaly within its own polity as the sole remaining territory that is in effect still solely governed from Westminster. Indeed, our recent report Devolving English government – part of the Institute for Government and Bennett Institute’s joint Review of the UK Constitution – shows that England is more centralised than most comparable OECD and European countries, and is a complete outlier given the size of its population.

While there has been considerable discourse about the nature and implications of the centralised approach to the management of English affairs, it is important to consider the full range of structural problems and institutional weaknesses affecting England’s governance. The scale of the task that lies ahead should not be underestimated.

England is governed by an incoherent tangle of institutions and bodies

One of the most notable characteristics of English administration is the sheer complexity of the organisation of local government, with each area governed by a slightly different combination of tiers and institutions. At the same time, various bodies answerable to central government implement policies and deliver services at the local level. Each of these uses its own geography, none of which entirely align with the local government boundaries. The consequence is a system that nobody fully understands, least of all the general public, creating a broader lack of clarity about who is actually responsible for service outcomes.

Another layer of complexity exists at the interface between the administration of England and the UK as a whole. The position of England in the union remains largely unaddressed, as devolution has developed elsewhere with implications for how parliament and the UK government handle English affairs. The ingrained reluctance in British government and politics to recognise England as a coherent and distinctive territorial entity has been an important obstacle to the development of a model of devolution that reflects England’s variable geographical character. It has also resulted in the continued intertwining of UK-wide and England-specific functions within each Whitehall department.

There is a democratic deficit in existing models of local government

There is also an enduring tendency for councils to be held more accountable to Whitehall than to the populations and locales they serve. This reflects an enduring centralist mindset which means that the media and large parts of the public see ministers as the accountable agents for failures in policy and service provision, even when these are formally the responsibility of lower levels of government.

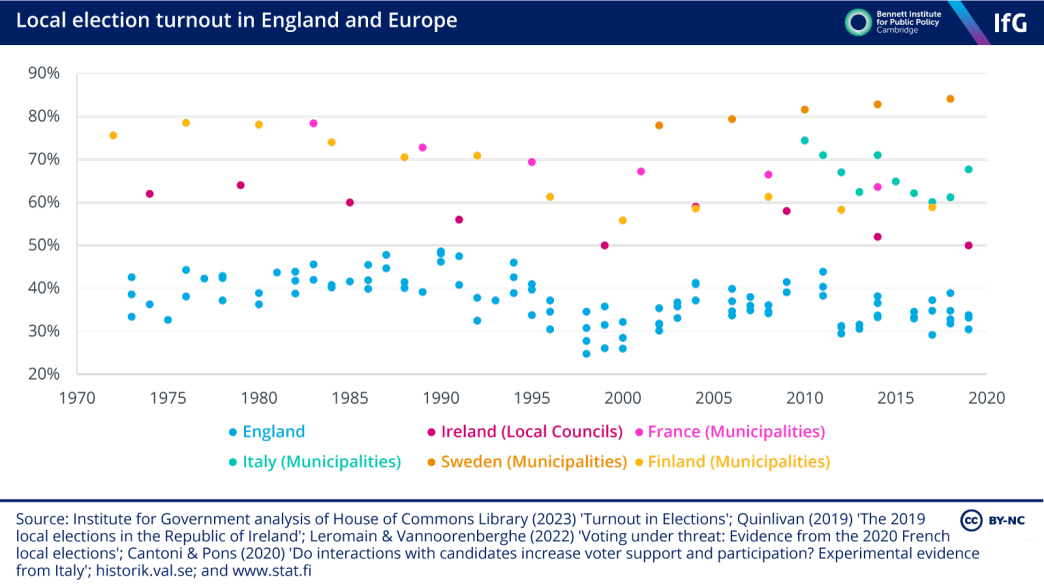

The upward model of accountability is both cause and effect of a concerning democratic deficit at the local level. Turnout in England’s local elections is consistently lower than any of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and considerably lower than other comparable countries. This relative lack of political engagement is also reflected in a lack of understanding among the public about how local government works.

Particular confusion surrounds newer institutions such as mayoral combined authorities, brought in to govern nine city-regions since 2011 – in a 2021 survey more than half of respondents in the then newly established West Yorkshire Combined Authority didn’t even know they had a mayor. 8 Centre for Cities, ‘What do the public think about devolution and the metro mayors?’ Data dashboard, October 2021, www.centreforcities.org/data/what-do-the-public-think-about-devolution-and-the-metro-mayors/ Such misunderstandings are indicative of a wider lack of public understanding and engagement in local politics, which act as major barriers to further devolution.

Change must begin in the heart of central government

Often the ‘cures’ advanced by central government to the ills of local government have ended up worsening the disease. And the treatment of these issues as political footballs by the two main parties has meant that, on the question of English devolution, the British political establishment has over successive decades been going round in circles. If devolution in England is to be given the chance to bed in and progress over the coming years, new structures and approaches are needed in Whitehall.

Our report argues for the establishment of new institutions responsible for protecting and deepening the English devolution process:

- an independent commission on English governance

- a commitment from both political parties to complete the devolution map by 2030

- an English Devolution Council representing local government at the centre

- a new England Office and England-focused cabinet committee

- the codification and entrenchment of the rights and responsibilities of local government.

Together these institutions would provide a platform from which central and local politicians can work in partnership as they begin the long-term process of repairing England’s over-centralised, incoherent, and democratically deficient model of governance.

- United Kingdom

- England

- Position

- Metro mayor

- Combined authorities

- West Yorkshire Combined Authority

- Publisher

- Institute for Government