Presumed consent? The role of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in the Brexit process

There has been debate over whether the devolved legislatures could hinder Brexit via the ‘legislative consent’ convention

In the aftermath of the EU referendum, there has been debate over whether the devolved legislatures could hinder Brexit via the ‘legislative consent’ convention. George Miller explains what this is and how it works.

Ever since devolution to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland began in 1999, the UK Government has operated according to the ‘Sewel’ or ‘legislative consent’ convention. Under this convention, Westminster will not normally legislate on devolved matters without the agreement of the devolved parliaments and assemblies.

Given the stark political differences over Brexit, the legislative consent issue could spark serious conflict between the UK and the devolved governments. The Scottish First Minister, Nicola Sturgeon, has said that she could not contemplate giving consent to legislation that would take Scotland out of the European Union (EU) ‘against the express will of the Scottish people’, and there has been debate in Wales and Northern Ireland about whether those nations’ devolved assemblies will get to ratify the final Brexit deal.

Agreeing on the need for consent

When Westminster legislates in devolved areas, ‘legislative consent motions’ are passed in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to allow the UK Parliament to proceed. This process may come into play to enable Westminster to implement Brexit (for example, if Westminster chooses to repeal the European Communities Act 1973 or amend the devolution statutes to remove references to EU law).

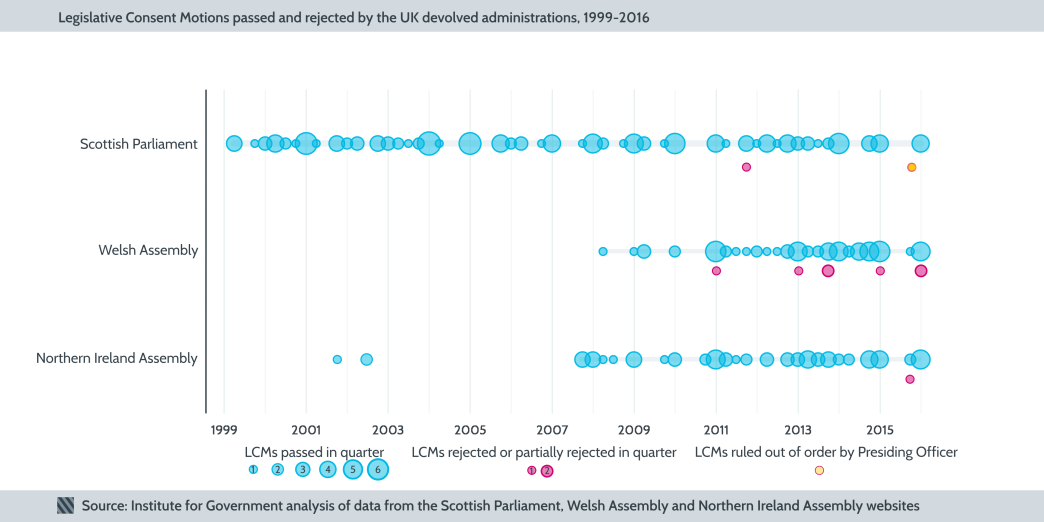

A look at the use of these motions to date shows that there have only been a few cases where the UK and devolved governments have failed to agree on whether consent is required. These disagreements have been most frequent in Wales, where the line between reserved and devolved responsibilities is sometimes unclear. There was also disagreement between the UK and Scottish Governments over the Trade Union Bill back in December. The Scottish Government sought to withhold consent on the bill, while the UK Government argued that the legislation was in wholly non-devolved areas. In the event, the Presiding Officer agreed with the UK Government and ruled that the bill did not require a consent motion.

These are exceptions rather than the rule, and there has generally been effective communication and agreement on when consent is required. On the issue of Brexit, the Prime Minister has promised to seek an agreed approach with the devolved governments, but whether this will extend to seeking their consent on the terms of Brexit remains to be seen.

Providing and withholding consent

If consent was withheld, this would mark a break from what has generally been a history of collaboration and consensus.

The Scottish Parliament has also only withheld consent on one occasion, when it objected to provisions in the 2011 Welfare Reform Bill where the introduction of the politically controversial Universal Credit impacted upon devolved services.

But what is striking is the frequency with which devolved legislatures have given consent; 158 legislative consent motions have been passed by the Scottish Parliament since 1999. The assemblies in Northern Ireland and Wales have also frequently passed motions since 2007, when the suspension of devolution in Northern Ireland ended and when the Welsh Assembly gained substantive legislative powers. Since then, the Northern Ireland Assembly has passed 72 motions and the Welsh Assembly has passed 65.

Agreement over legislative consent motions has persisted despite party political tensions. In Scotland, their frequency in the early years of devolution led to accusations that Holyrood was abdicating its responsibilities and becoming a ‘copycat parliament’. But even the SNP, which opposed two thirds of consent motions passed between 2003 and 2007, has since recognised the usefulness of the legislative consent procedure, as illustrated by the regular use of this mechanism since the party came to power in 2007.

In a number of cases, legislative consent motions have been passed simply because their use is uncontroversial and convenient: many are used to implement UK-wide systems or frameworks consistently (for example, the single legal framework set out in the Equality Act 2010), or to deal more easily with complex interactions between devolved and reserved competences, such as in the area of criminal justice.

But political consensus has been sought and achieved even in controversial constitutional circumstances. In November 2015, a legislative consent motion was used to allow Westminster the power to enact welfare reform legislation for Northern Ireland, after the Assembly had failed to pass its own welfare reform legislation for several years. Likewise, consent was sought and eventually given during the passage of the Scotland Act 2016, when the Scottish Government pledged to block the bill unless an acceptable deal was reached on a new fiscal framework.

What should Westminster do?

Brexit is clearly a divisive issue and one where devolved legislatures could take the opportunity to use the legislative consent convention formally to register their protest. But Westminster has previously been willing to engage and build consensus, particularly in cases of constitutional significance.

If the UK Government were to force Brexit through in the face of opposition from the devolved legislatures, not only would there be a potential legal challenge (the Scotland Act 2016 and the current Wales Bill 2016-17 recognise the legislative consent convention in statute, albeit in a form that makes it unlikely that the courts would rule against Westminster), but the political consequences could be hugely destabilising.

Legislative consent has operated largely successfully based on engagement and consensus. When legislating to implement Brexit, serious efforts should and will be made to secure the prior agreement of the devolved nations. For Westminster to force its will through without consent would not be completely unprecedented, but it would go against the history of the legislative consent process, and the constitutional importance of Brexit legislation would make this deeply controversial.

- Topic

- Brexit Devolution

- Country (international)

- European Union

- United Kingdom

- Scotland Wales Northern Ireland

- Administration

- May government

- Department

- Department for Exiting the European Union

- Legislature

- Scottish parliament Senedd Northern Ireland assembly

- Publisher

- Institute for Government