Brexit consequentials: why the UK must involve the devolved governments in the process of leaving the EU

The shockwaves from yesterday’s earthquake continue to reverberate through the political landscape. The Prime Minister has been toppled, and the existing differences between the UK’s four nations threaten to widen into serious rifts. In particular, the place of Scotland in the UK – supposedly settled for a generation two years ago – is again in question. Akash Paun explains.

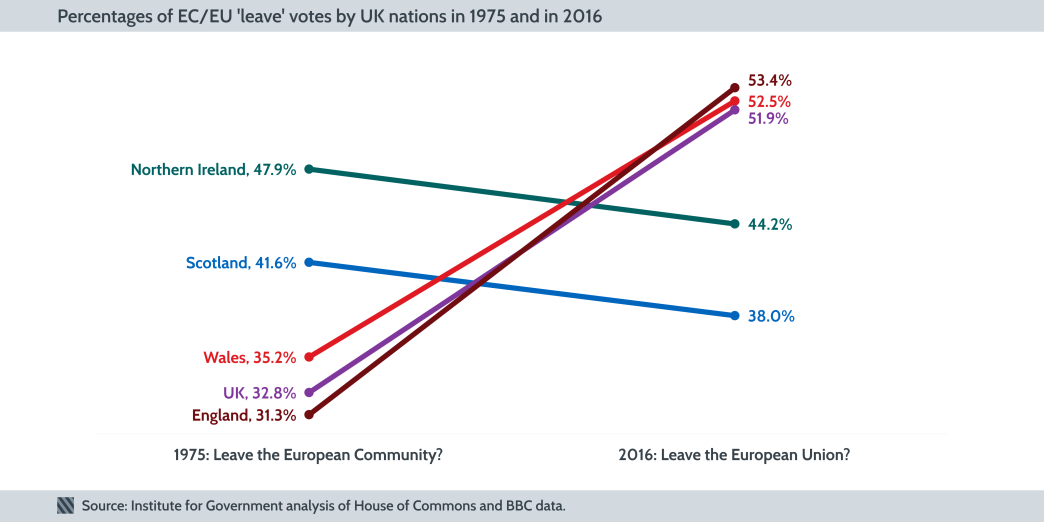

Every single local authority area in Scotland voted Remain. Meanwhile, with the exception of London, every region in England voted Leave, as did Wales. Northern Ireland voted narrowly to remain, but with a large minority, mainly from the unionist community, opting for Leave, in line with the preference of Northern Ireland’s unionist First Minister.

The outcome flipped the pattern of the 1975 European Economic Community (EEC) referendum, when England was the most pro-Europe of the four nations, while Scotland and Northern Ireland were more sceptical about the European project. On that occasion, though, Remain was supported by a majority in each of the four nations, and a total of two-thirds of all UK voters, so there was no sense in which the outcome was being imposed against the will of any part of the UK.

The situation today is very different and territorial tensions are running high. Nicola Sturgeon, Scottish First Minister, has already announced that a second referendum on Scotland’s independence is now ‘on the table’ – although Westminster’s agreement would be needed for any such poll. The SNP would only be likely to want to hold such a poll if it was confident of victory – not a given, even in the context of Brexit. But placing the issue back on the table will concentrate minds in Westminster.

Meanwhile Sinn Féin is calling for a ‘border poll’ on the reunification of Ireland, to avoid a hard border being created between the northern and southern parts of Ireland. Again, this could only happen with UK government consent, which will not be forthcoming. But simply by raising the issue Sinn Féin has shone a light on the possibility that power-sharing in Belfast may be destabilised by the Brexit vote. The UK Government will be anxious to avoid this outcome. Like England, Wales voted to leave, but the Welsh Government is strongly pro-Remain, and will regard the prospect of Brexit with grave concern, given its reliance on EU funding. Meanwhile, there has even been social media chatter about pro-EU London declaring independence from the rest of England.

While this is clearly not a serious proposition, a more plausible scenario is a sustained push from London and its new Mayor, Sadiq Khan, to raise and retain a greater share of taxation. In this fevered context, David Cameron sensibly declared in his resignation statement that the negotiations on the terms of Brexit ‘will need to involve the full engagement of the Scottish, Welsh and Northern Ireland governments to ensure that the interests of all parts of our United Kingdom are protected and advanced.’ These words must now be turned into action. There is existing machinery for involving the devolved governments in EU matters, but this has ceased operation in recent months. The last meeting of the Joint Ministerial Committee on Europe was in December 2015, which meant that, to their frustration, the devolved governments were barely involved in the EU ‘renegotiations’ of early 2016. Carwyn Jones, First Minister of Wales, complained of learning about the UK’s reform priorities via the pages of the Sunday Telegraph.

The UK Government will have to do better this time, both to avoid a bloody political row, and also since under the terms of the ‘Sewel Convention’, the devolved legislatures will expect to be asked for their consent before Westminster can ratify the terms of a Brexit deal. This is because much EU law is given effect through the devolved Scottish and Northern Ireland legal systems, and also because Brexit will change the powers of the devolved bodies, for instance by repatriating from Brussels powers over agriculture, the environment and fisheries. Money is also likely to be at the heart of negotiations between the governments of the UK. The devolved bodies, as well as local government in England, will want reassurance that the UK Government will recompense them for EU budget streams to which they lose access.

On a per capita basis, Wales receives six times as much money from EU structural funds as England. And all three devolved nations receive several times as much per person from the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy as does England. The UK Government faces complex and lengthy negotiations with the other 27 member states of the EU over the coming years. But whoever replaces David Cameron as Prime Minister in October must also take seriously the domestic side of the negotiation process, in which consensus between all the governments of the UK should be sought. If this proves impossible to achieve, then the Union of 1707, as well as that of 1973, may once again be imperilled.

- Topic

- Brexit Devolution