Northern Irish power-sharing talks must be a UK government priority

The Government must not let Brexit distract from making a success of renewed power-sharing talks in Northern Ireland.

The Government must not let Brexit distract from making a success of renewed power-sharing talks in Northern Ireland, writes Jess Sargeant.

The absence of a Northern Ireland executive and assembly since January 2017 has created a void of accountability and has left Northern Ireland, as a whole, without a voice in the Brexit process.

So the renewal of multi-party talks on power-sharing in the Northern Ireland Executive, more than 800 days since the power-sharing arrangements collapsed and after five rounds of talks ended in failure, is encouraging. Brexit has dominated the Government’s bandwidth in Westminster, but space must made for – and serious effort put into – restoring a functioning government to the most divided and complicated part of the United Kingdom. It is imperative that these talks make progress.

The absence of an executive has created a democratic deficit in Northern Ireland

The UK Parliament can ensure the continued functioning of public services in Northern Ireland by passing budgets and setting local tax rates, and the Northern Ireland (Executive Formation and Exercise of Functions) Act 2018 enabled civil servants to take some decisions.

But without its own executive and assembly, Northern Ireland has been left without the ability to make important decisions on public services or develop new policy. It also has no representation in the Brexit process other than via DUP MPs, who have significant influence at Westminster but cannot speak for the whole of Northern Ireland.

Our Devolution at 20 report identifies the absence of an executive in Northern Ireland as one of the seven biggest challenges for devolution in the next decade.

The structure for the talks is comprehensive – and the issues to be discussed are complicated

The latest rounds of talks will consist of weekly leader level roundtables involving the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, the Irish Tánaiste (Deputy Prime Minister) and the leaders of the five main political parties in Northern Ireland. Five working groups consisting of three representatives from each party have also been established. One will consider the future policy programme, one will look at ‘rights, language and identity’, and the remaining three will consider various aspects of Northern Ireland’s future governance.

The comprehensive structure of the talks could be interpreted as a promising sign if it represents a serious commitment to resolving a broad range of long-term issues. Conversely, if nothing can be agreed until everything is agreed, it could simply create more opportunities for a log-jam.

There are also many contentious issues on which agreement will need to be reached. Arlene Foster, the DUP leader, is said to have been unable to sell a previous deal involving an Irish Language Act to the party’s grass roots, while the DUP and Sinn Féin will need to move their positions on legacy issues – such as inquests into killings during the Troubles – and equality and rights issues like same-sex marriage.

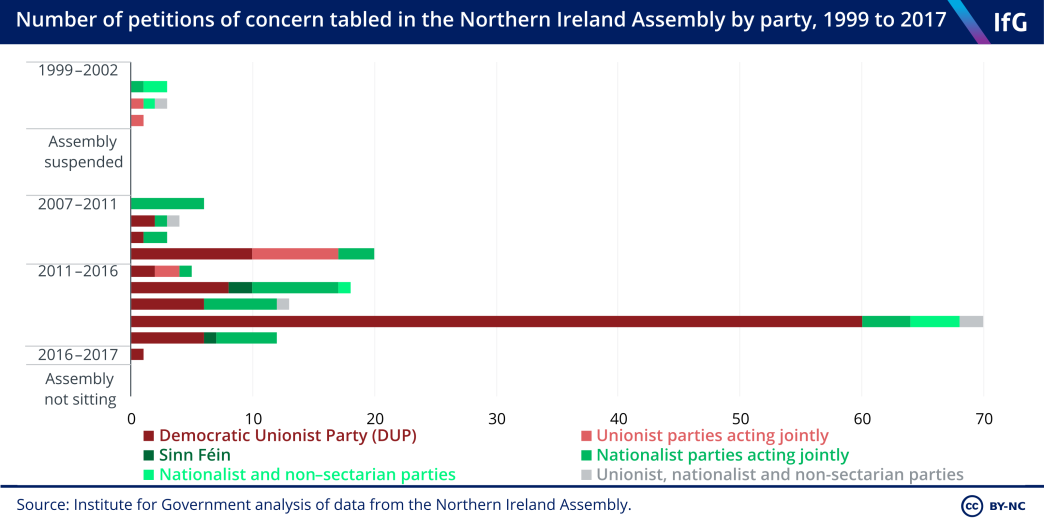

Arrangements will also need to be put in place to guard against a future collapse of any assembly. For example, in 2015 the Assembly backed same-sex marriage, but the DUP blocked progress through a petition of concern – a mechanism, designed to protect the interests of both communities, that allows 30 assembly members to require ‘cross-community’ support for a vote. The use of the mechanism has increased significantly since 2007, prompting all major parties to argue for reform and the creation of a working group to explore how this could be achieved. In 2015 the DUP and Sinn Féin agreed a protocol to limit its use, but this has not been fully implemented.

Commitment by the UK Government is necessary – but not sufficient – to deliver a breakthrough

Drawing on his own experience as a leading player in the Good Friday Agreement negotiations and the formation of the Assembly, Tony Blair said, in an interview with the Institute for Government, that power-sharing in Northern Ireland “can be put back together again but it requires intensive work” – not least by the Prime Minister. He recalled his own frequent visits to Belfast to facilitate negotiations between parties, because “showing that you really care about it is an important part of solving it”.

Brexit has dominated its time and energy, but the Government must make restoring devolved government in Northern Ireland a priority. But while a strong commitment from the UK and Irish Governments is key to facilitating an agreement, ultimately the success of the talks in Northern Ireland will depend on the willingness of parties in Belfast to compromise.

- Supporting document

- Devolution at 20.pdf (PDF, 1.87 MB)

- Topic

- Devolution Brexit

- Keywords

- The union

- United Kingdom

- Northern Ireland

- Devolved administration

- Northern Ireland executive

- Legislature

- Northern Ireland assembly

- Publisher

- Institute for Government