EU vaccine debate highlights UK success – and need for diplomacy

The UK’s vaccine rollout shows the government has learned from earlier mistakes in the crisis

The UK’s vaccine rollout shows the government has learned from earlier mistakes in the crisis – but it will need to get its approach to quarantine and vaccine diplomacy right, says Tom Sasse

The temperature of vaccine politics heated up this week as the European Commission entered a bitter row with AstraZeneca over reduced vaccine deliveries. Commission officials argued that AstraZeneca should make up the shortfall with doses from UK plants, while the company pointed to difficulties ramping up European production due to the short lead times it had been given by the EU.

The quarrel reflects tensions within the EU over the Commission’s approach to vaccinations and points to what the UK has got right in its own programme. It is also a reminder that the path out of the crisis will be complex, requiring skilful diplomacy.

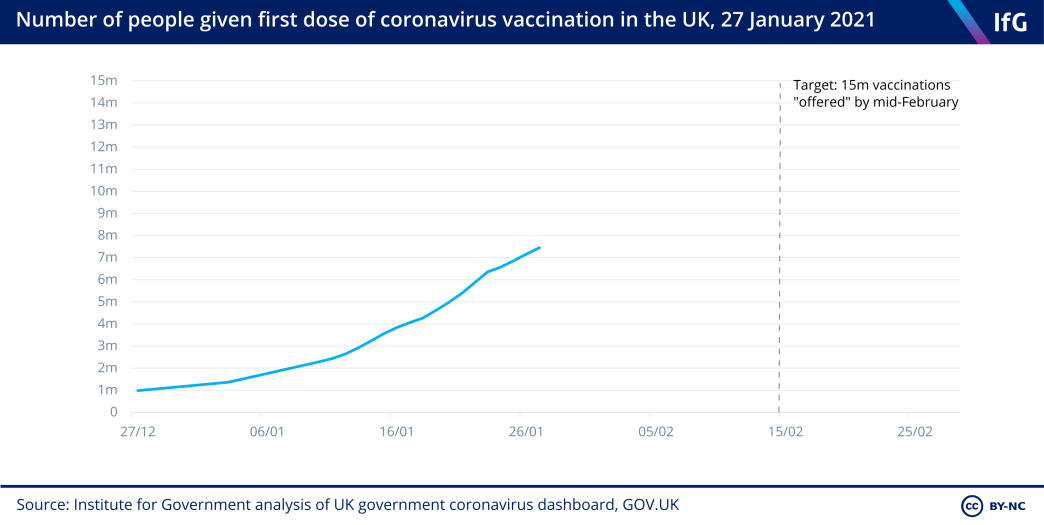

The government is on track to hit its mid-February target, while the EU has made a slow start

As of 29 January, just under 7.5m people in the UK had received their first dose of vaccine – including over three quarters of over 80s. With over one in nine people reached, the UK is behind only Israel, the United Arab Emirates and the Seychelles as a percentage of total population vaccinated. [1]

There are big challenges yet to come. The rollout will soon be extended to larger and harder to reach cohorts, demand for second doses will put extra pressure on the system, and any move to release restrictions – such as reopening schools – will raise question about priority. Ministers say supply is the only “rate-constraining” factor, but they have been cagey when asked for figures, citing vague concerns over “national security” and “commercial sensitivity”.

However, journalists who have pieced together leaked documents and data think, even though the government has less vaccine than it expected, it has enough – just about – to hit its mid-February target.[2]

Most European countries, by contrast, have reached only 1–3% of their populations. The EU’s programme, which the UK chose not to participate in, has so far not secured enough supply (although this could quickly change if the Johnson and Johnson vaccine, a single dose vaccine which the EU has ordered 200m doses of, is approved). For now, the Commission is under pressure from member states, several of whose vaccination programmes, barely off the ground, will be paused next week to protect scarce supplies.[3]

The speed of the UK’s rollout is testament to effective decision making, planning and execution

In a pandemic that has brutally shown up some of the shortcomings of the current UK government and state, it is worth pausing to reflect on what lies behind the UK’s success.

The government gave significant autonomy to the Vaccine Task Force – a small group mostly drawn from the private sector, led by Kate Bingham. A group of four ministers quickly signed off on contracts, allowing the Task Force to move quickly while the EU, even with much greater purchasing power, was caught up in bureaucratic negotiations.[4] Whatever doubts there were in government over which, if any, vaccines would work, the government’s overall calculation of risks, costs and benefits was right.

Ministers also appeared to learn from the PPE crisis last spring, where supply was similarly choked by huge international demand. Then they were caught unprepared, without a large stockpile or contingency plans to adapt supply chains. This time the government supported the Oxford initiative, invested in domestic supply chains, and gave industry time to prepare.[5] Vaccination centres were not about to be caught without syringes, while a “push” model similar to the one it eventually developed for PPE was used to get vaccine out quickly.

Whereas local trust and expertise appeared essential in countries that did better than the UK at contact tracing, the health department and NHS’s “command and control” structure, which gives it tight oversight of what is essentially a complex logistical task, also appears better suited to overseeing a vaccinations than more federalised health systems in other countries.[6]

Big challenges remain – not least getting quarantine and vaccine diplomacy right

However, no country will escape the Covid crisis alone. With the virus prevalent around the world and the risk of vaccine-resistant variants emerging, exit strategies will depend on international efforts to control transmission, vaccinate people, track mutations, and limit their spread across borders. While some countries have succeeded in driving down transmission, the human and economic cost of harder borders will continue to be severe while prevalence remains high elsewhere.

In the UK, reaching the “new normal” – where many lockdown measures can be lifted but restrictions on travel and some public health measures remain in place – will rely on the government’s hotel quarantine policy and contact tracing system proving capable of defending the gains made by mass vaccination. But the government’s current approach at the border risks the worst of both worlds: considerable costs without the security afforded by a stricter policy.

While many will see the European Commission’s behaviour this week as unreasonable, it raises the unavoidable question of how countries collectively negotiate over limited vaccine supply in the coming months. Those in a good position, like the UK, have a moral – if not contractual – obligation to help other countries vaccinate their vulnerable, particularly given encouraging news of further vaccines approaching approval.

Building on the UK’s scientific and administrative success, the government should lead generously on this front – surely be the best way to begin to sketch a post-Brexit role for “Global Britain”.

[1] Our World in Data, Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations, https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations

[2] Heffer G, COVID-19: Almost four in five of over-80s have received first dose of coronavirus vaccine but supply is 'tight', says Matt Hancock, Sky News, 25 January 2021, https://news.sky.com/story/covid-19-almost-four-in-five-of-over-80s-have-received-first-dose-of-coronavirus-vaccine-12198701

[3] Financial Times, Shortfall in jabs pushes EU vaccine drive to crisis point, 28 January 2021, www.ft.com/content/1b2afe60-b5e6-456d-98e0-313fe664d0b9

[4] Deutsch J and Wheaton S, How Europe fell behind on vaccines, Politico, 27 January 2021, www.politico.eu/article/europe-coronavirus-vaccine-struggle-pfizer-biontech-astrazeneca/

[5] Robert Peston, Twitter, 26 January 2021, https://twitter.com/Peston/status/1354019140084916225

[6i] Giles C, Cookson C, Neville S and Cameron-Chileshe J, UK vaccination rollout a rare pandemic success, Financial Times, 18 January 2021, www.ft.com/content/cdfb7b28-8306-4db2-8dd6-4f85a92b1778

- Topic

- Coronavirus Brexit

- Keywords

- Health

- Country (international)

- European Union

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Publisher

- Institute for Government