The coronavirus has changed general practice – but it is not yet a virtual service

The greater use of remote appointments in general practice will need to be carefully evaluated when this crisis is over

Graham Atkins argues that greater use of remote appointments in general practice will need to be carefully evaluated when this crisis is over

Since the coronavirus lockdown was announced on 23 March, GPs have moved fast to radically change how they provide primary care. The shift is part of a wider lockdown trend as face-to-face meetings are increasingly replaced by online and telephone equivalents.

This has been long-predicted – and it will be welcomed by many patients and policymakers alike. However, as with all changes to public service delivery introduced during the lockdown, it will need careful evaluation once the crisis is over.

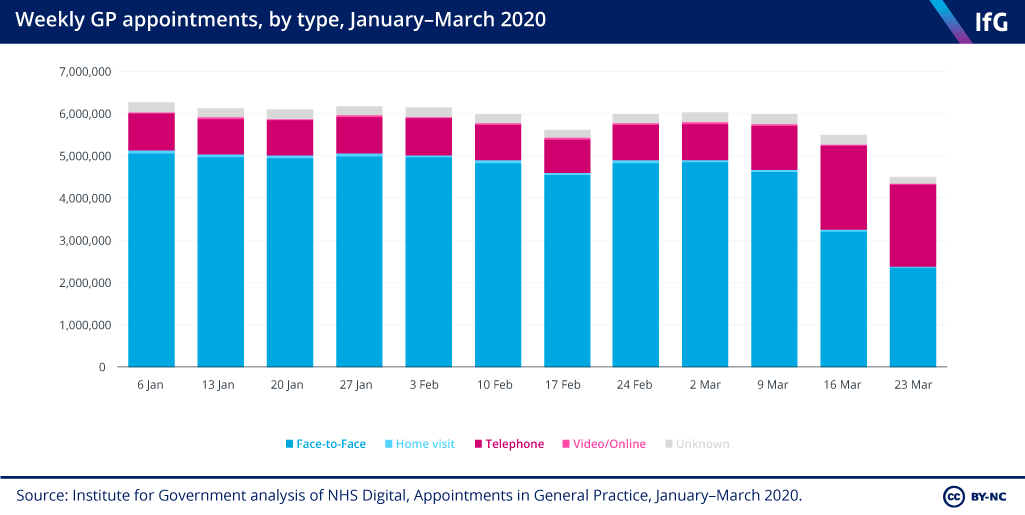

The number of GP appointments has fallen rapidly since the coronavirus outbreak

There has been a big fall in GP appointments since the onset of coronavirus – even before the government announced the full lockdown on 23 March. There were 4.5 million appointments in the final week of March this year, a 21% decrease on the 5.7 million appointments in the final week of March 2019.

Some of the decline may reflect that GPs are not recording online or video appointments in their books. But the size of the fall, and the comparable fall in people accessing other health services such as Accident and Emergency departments over the same time period, suggests that there has been a genuine reduction in GP appointments.

Some patients with minor illnesses will be self-managing their symptoms following government guidance to use telephone or online services to contact GPs. But the reduction in numbers will also be because patients are no longer presenting with serious illnesses and are instead choosing to stay away from their local surgery for fear of contracting coronavirus. There has been a significant fall in the number of patients presenting with gastroenteritis (serious stomach bugs) and vomiting, with both below the trend for recent years. On the other hand, appointments involving other serious cases such as myocardial infarction (heart attacks) have increased quickly, possibly due to the rapid decline in the number of patients showing up at Accident & Emergency during the crisis.

The fall in appointments is a shock rather than a trend. The government’s own research suggests that half of GP appointments are from patients who have long-term conditions – people who are unlikely to have stopped needing care. The government cannot, and should not, assume that this reduction in face-to-face appointments will be sustained.

GP appointments are increasingly remote

Telephone and online appointments have been on the rise for a number of years, but the pace of change has not been fast. The share of GP appointments conducted by telephone increased from 5% (2012) to 9.3% (2018), and online video appointments increased at an even slower rate, from 0% in 2016 to 0.1% in 201he

The coronavirus outbreak has accelerated these trends. Due to the difficulty of remaining two metres apart in a GP surgery, and NHS England’s edict that GPs see avoid face-to-face appointments wherever possible, 43% of appointments were conducted by phone in the last week of March and 0.4% were conducted online. The coronavirus crisis has forced more change in the last two months than in last six years.

Central funding for video appointment software, and some private companies making their products available for free, has clearly helped the rise in remote appointments during this crisis. This is good news. If GPs hadn’t been able to offer appointments remotely, many people would not have been able to access care and advice at all.

But policy makers should note that the huge majority of these appointments did not require new technology, with 1.9 million appointments conducted over the phone in the last week of March compared to just 17,000 appointments online. There are many variants of new online video software, but finding secure services for patients to send pictures to GPs during phone appointments would be a better use of effort than pressuring GPs to adopt new forms of software..

Remote appointments will need careful evaluation after this crisis

There are many reasons to cheer the shift to remote appointments. Some – primarily younger – patients prefer remote appointments and some studies show that remote appointments are shorter than face-to-face ones, and therefore reduce costs. And, of course, it is clearly better for GPs to offer more remote appointments than to reduce access to primary care.

But pushing for ever more remote appointments once the crisis is over should not be the default position. There is still much we don’t know about their success as a method of speaking to a GP. Most evaluations of remote appointments have been of video consultations for hospital appointments: these are primarily made up of clinically-stable patients, not some of the more vulnerable patients that GPs often see. The government needs to undertake or commission research into:

- Follow-ups – are patients who have remote appointments more likely to need to come in for repeat appointments?

- Clinical behaviour – do GPs prescribe more ‘just-in-case’ medicines in remote appointments?

- Patient satisfaction – are remote appointments appropriate for all patients?

- Do remote consultations work well for older and/or vulnerable patients?

Coronavirus is triggering a whole new way of working, and some old ways will never return – but the government must fill the gaps in its knowledge before it tries to make general practice a fully virtual service.

- Topic

- Public services Coronavirus

- Keywords

- Health

- Publisher

- Institute for Government