Levelling up: where does government spend money?

The government has committed to tackling regional inequalities as part of its ambition to ‘level up’ different parts of the UK.

The government has committed to tackling regional inequalities as part of its ambition to ‘level up’ different parts of the UK. This has led to renewed interest in the allocation of public spending across different parts of the country.

Government officials have indicated that, as part of levelling up, the government wants to improve the quality of data on where the government spends money.[1] This explainer sets out what data is currently available on the geographic allocation of public spending and what that shows.

How is spending allocated across the country?

There are numerous different government organisations and agencies which spend public money, such as central government departments, arm’s length bodies (ALBs) of government departments, mayoral combined authorities (MCAs), local government and the devolved administrations.

The money the devolved nations of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland can spend is determined by the Barnett formula and the revenues raised from devolved taxes. The devolved administrations then have discretion over how that money is spent across areas of spending that are devolved, while the UK government spends money across the UK on ‘reserved’ areas, such as defence.

There is not a consistent system of ‘regional authorities’ across England so the government does not allocate a single budget to each region. Central government departments, or ALBs accountable to those departments, direct around 80% of all public spending within England.[2] The departments do not have any specific requirement to spend the same amount of money per head in different regions.

The remaining fifth of public spending is done by subnational governments in England, such as local councils and MCAs. Over three-quarters (77%) of local government revenue comes from local taxes, through council tax and business rates, with the remainder coming from central government grants.

How much variation in spending is there across the UK nations and region?

Not all spending can be allocated to a region. For example, debt interest spending does not go to a particular location. However, Treasury data identifies the region where spending occurs for 85% of all spending.[3] Throughout this explainer, we focus on this identifiable spending.

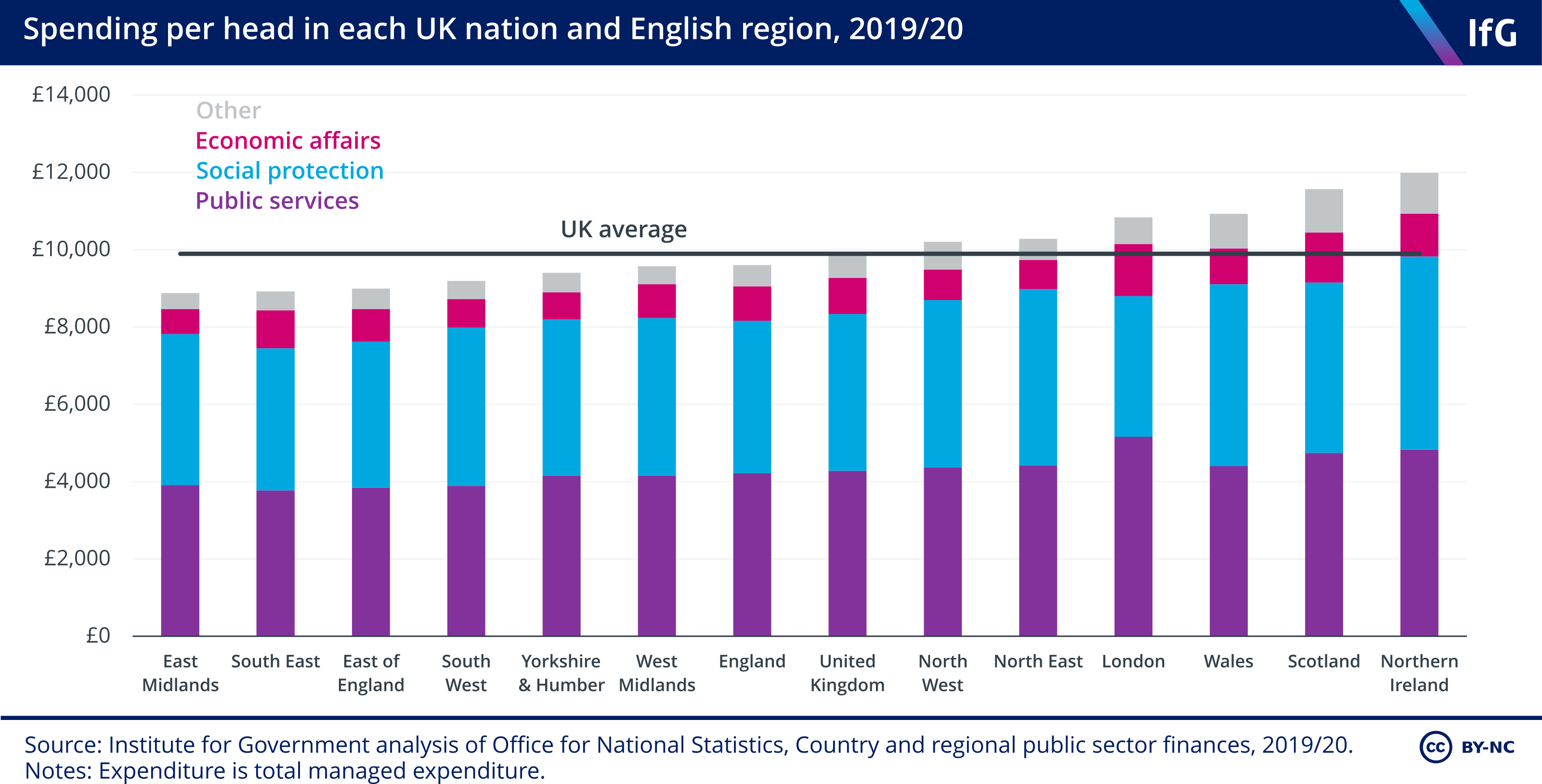

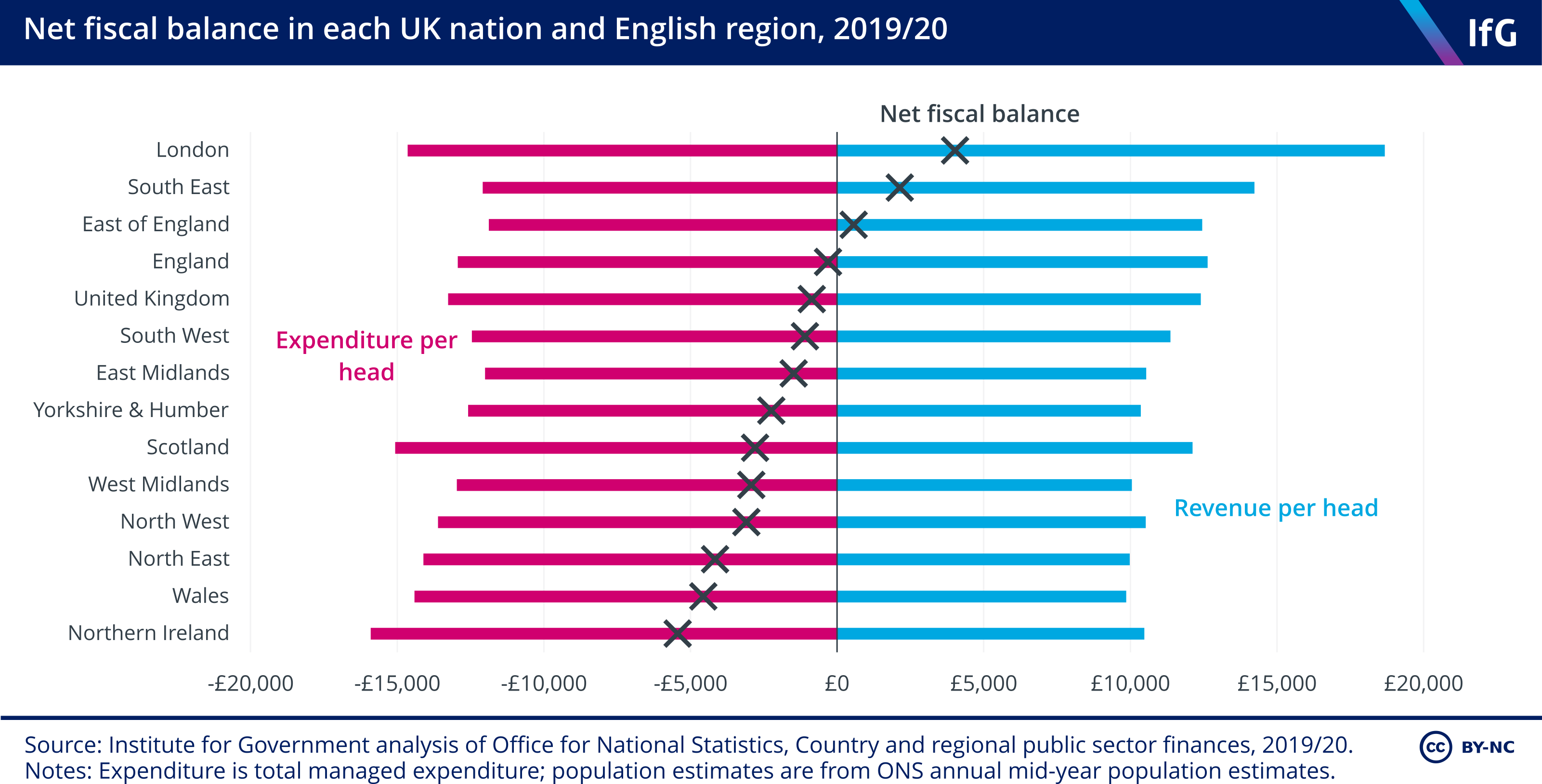

Spending per person in England as a whole and in each English region (except London, the North West and the North East) is lower than the UK average. The devolved nations of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland receive more money on a per person basis than every other English region, except London. This is because the Barnett formula takes as its starting point previous spending, and so higher spending in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland when the formula was first used (in 1979) has persisted.*

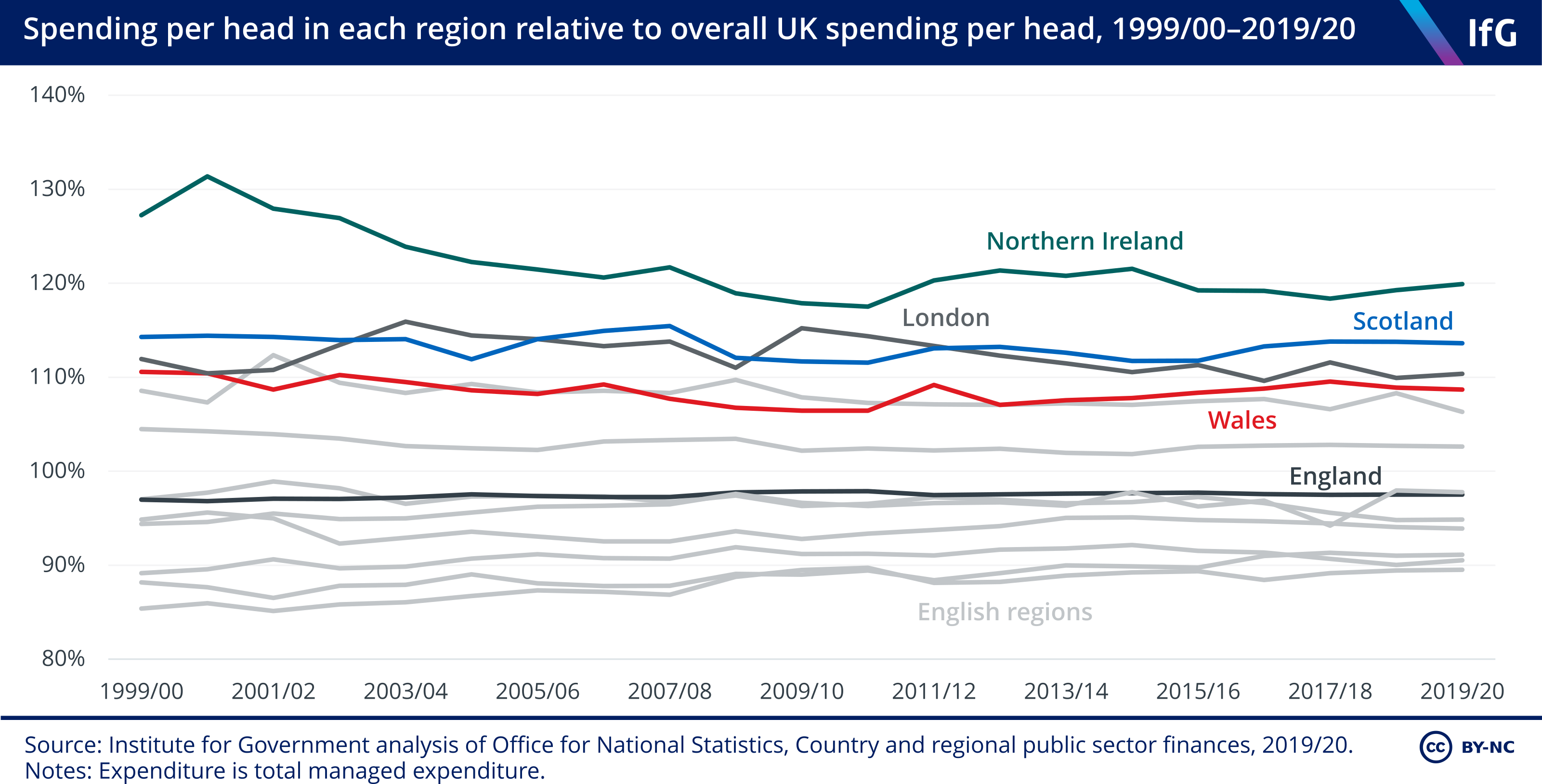

Differences in spending between the UK nations and regions have been relatively stable over the last 20 years, with Northern Ireland, Scotland, London and Wales occupying the top spots for around a decade.

What accounts for the differences in spending per head between English regions?

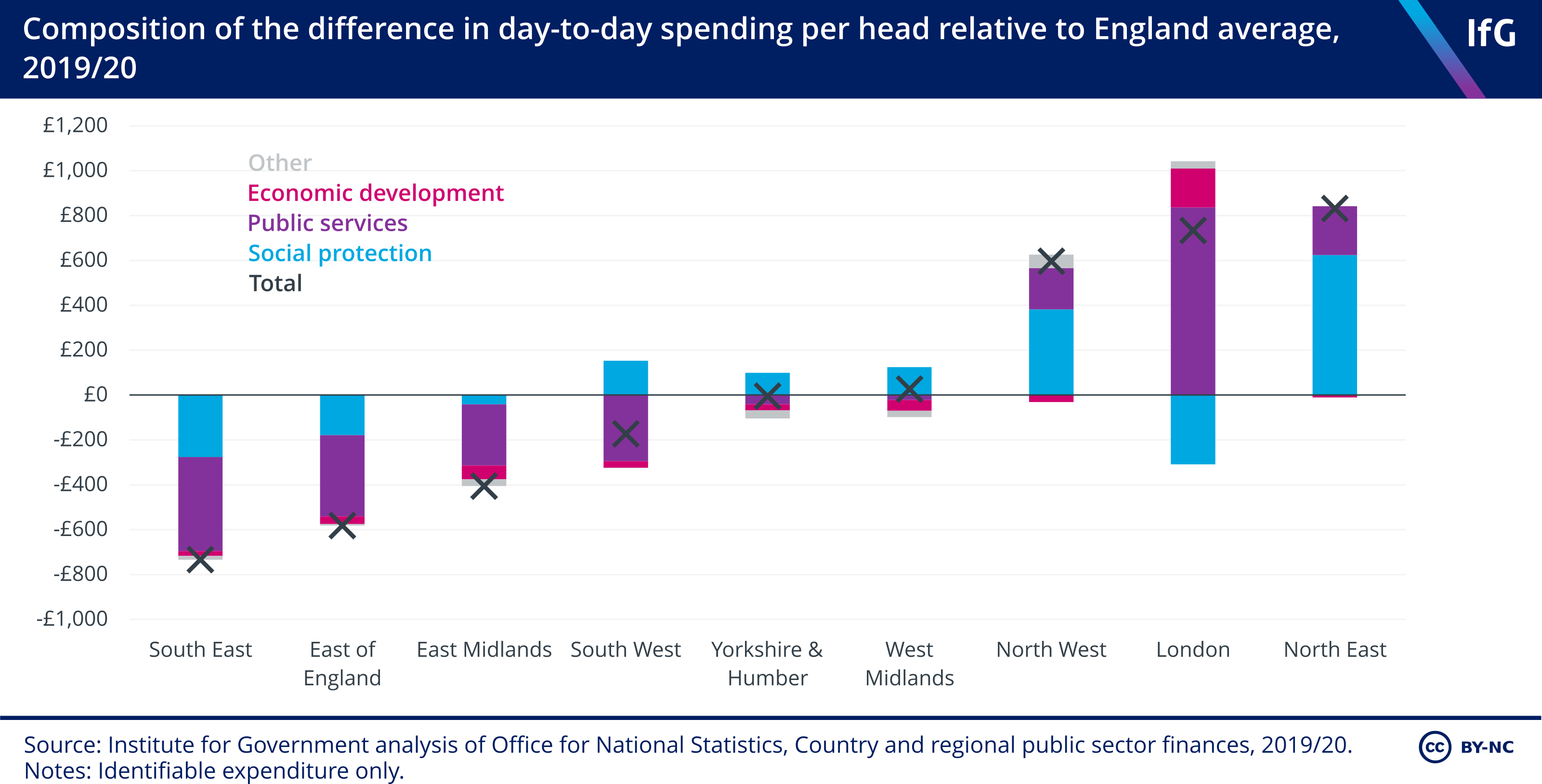

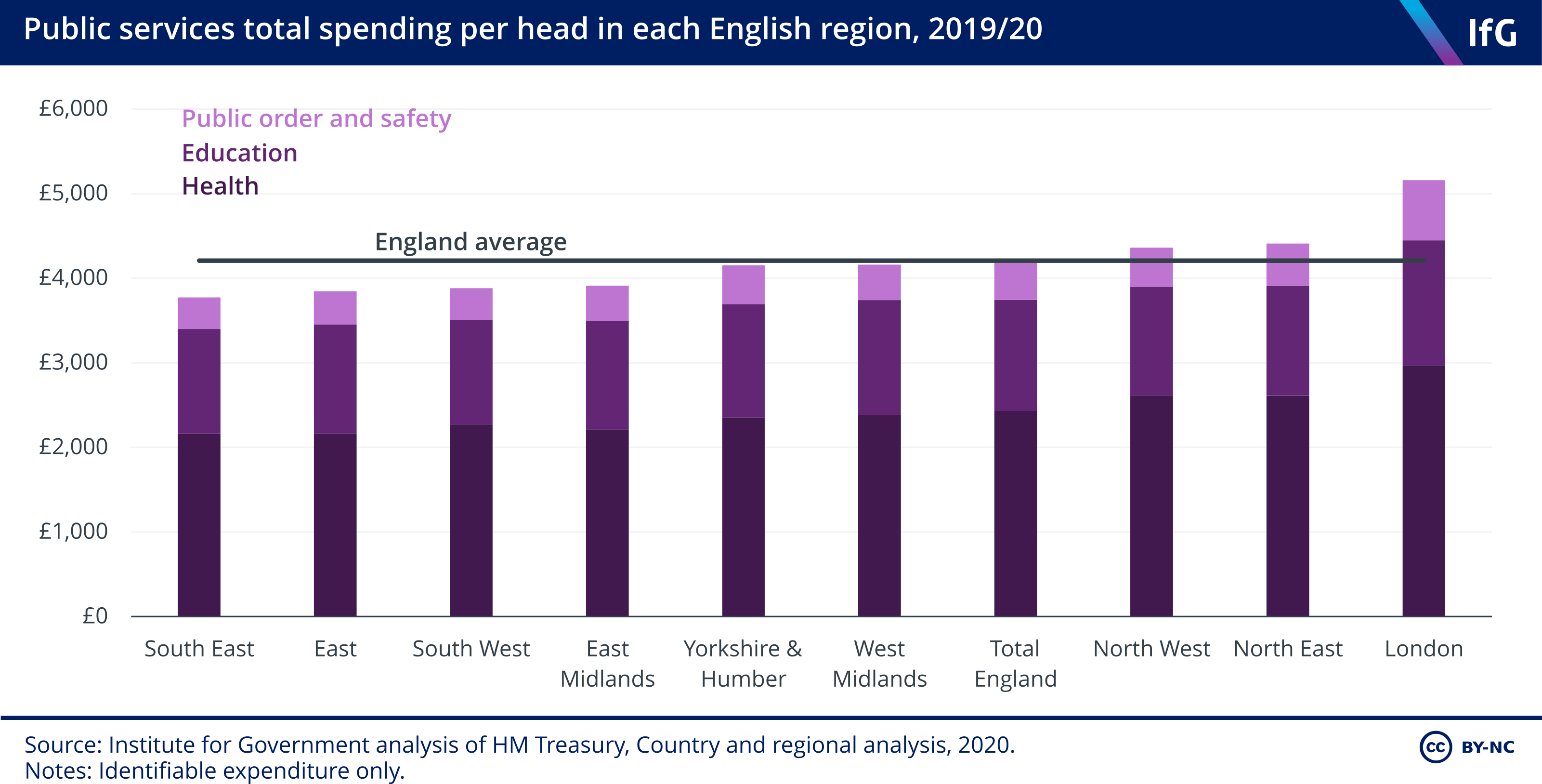

As well as the differences between the four nations, there are substantial differences between English regions in the level of spending per person. London has the highest spending per head in England at £10,835 per person. This is £550 more per head than the next highest (the North East) and £1,231 higher than the England average.

We can understand these differences better by examining which types of spending account for it.

Spending in London is higher both for day-to-day spending (which covers immediate expenditure, such as wages of public sector workers) and capital spending (which covers investment projects).

Differences in day-to-day spending

Three-fifths of the gap between per person spending in London and the England average is accounted for by higher day-to-day spending. The biggest categories of day-to-day spending are social protection (which includes income transfers to households through the state pension and benefit systems) and public services.

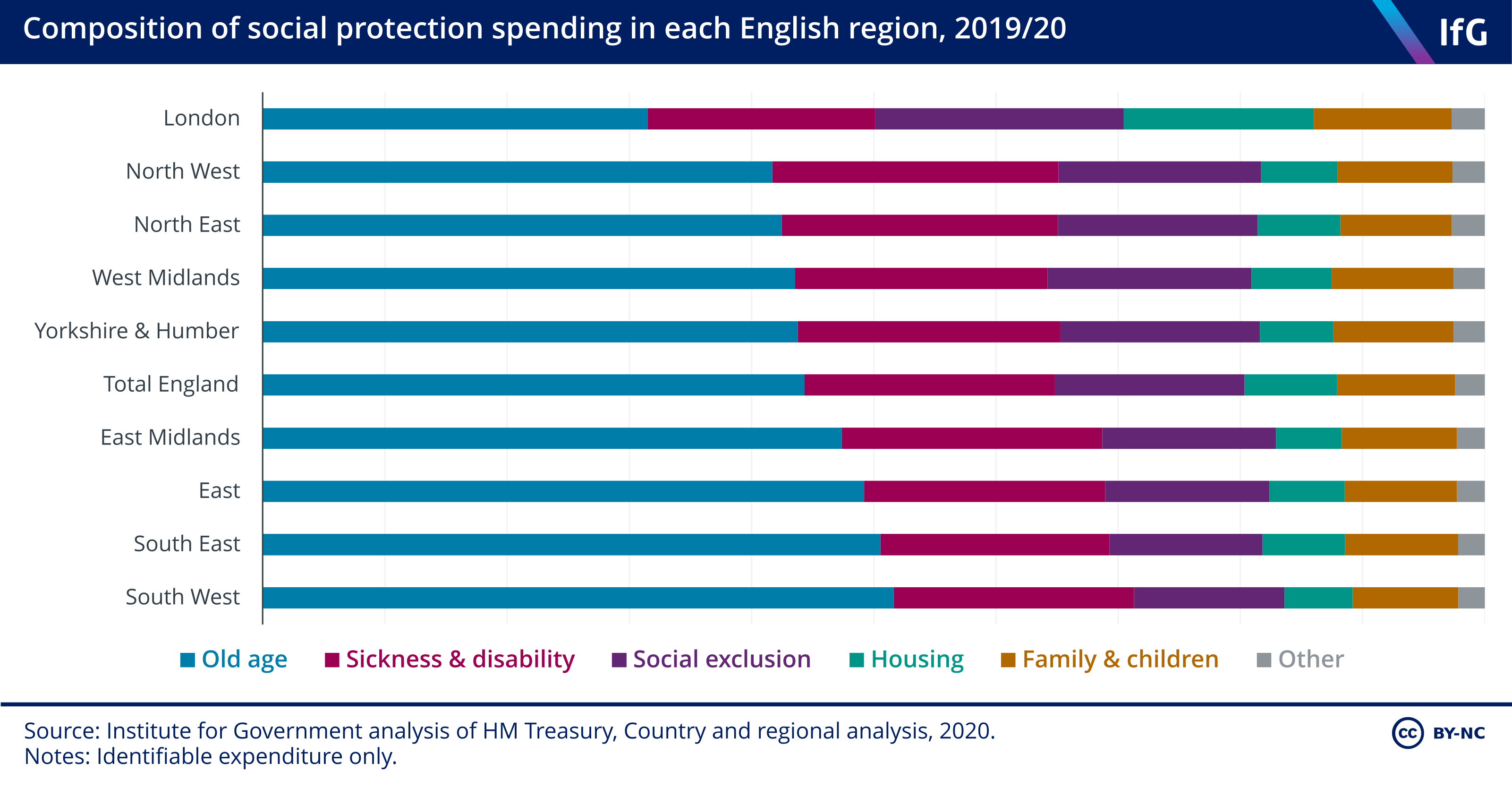

Spending on social protection is determined by nationwide rules which govern eligibility for state pensions, Universal Credit, housing and other welfare benefits. The London population is younger and incomes and employment rates are higher. As a result, people in London receive £309 less per person on average than the England average. Meanwhile, older and less affluent populations in the South West, Yorkshire and the Humber, West Midlands, North West and North East receive more than the England average in social protection spending.

Barely half of social protection in London is spent on sickness and disability payments or old age pensions and benefits compared to over 70% in the South West. Higher accommodation costs in London means that a much higher share of social protection spending goes on housing in London than elsewhere.

The other big category of day-to-day spend is public services. Spending on health and public order and safety are notably higher in London than in other regions. One of the main reasons for this is that specialist public service provision is concentrated in London. For example, the Metropolitan police have a broader remit for security, London courts such as the Old Bailey hear many of the most complex cases and specialist hospital units are more often found in London. People in other parts of the country will benefit from this spending, even though it takes place in London (for example, if they travel to London for treatment) and so these numbers may overstate the amount of spending on London residents compared with others.

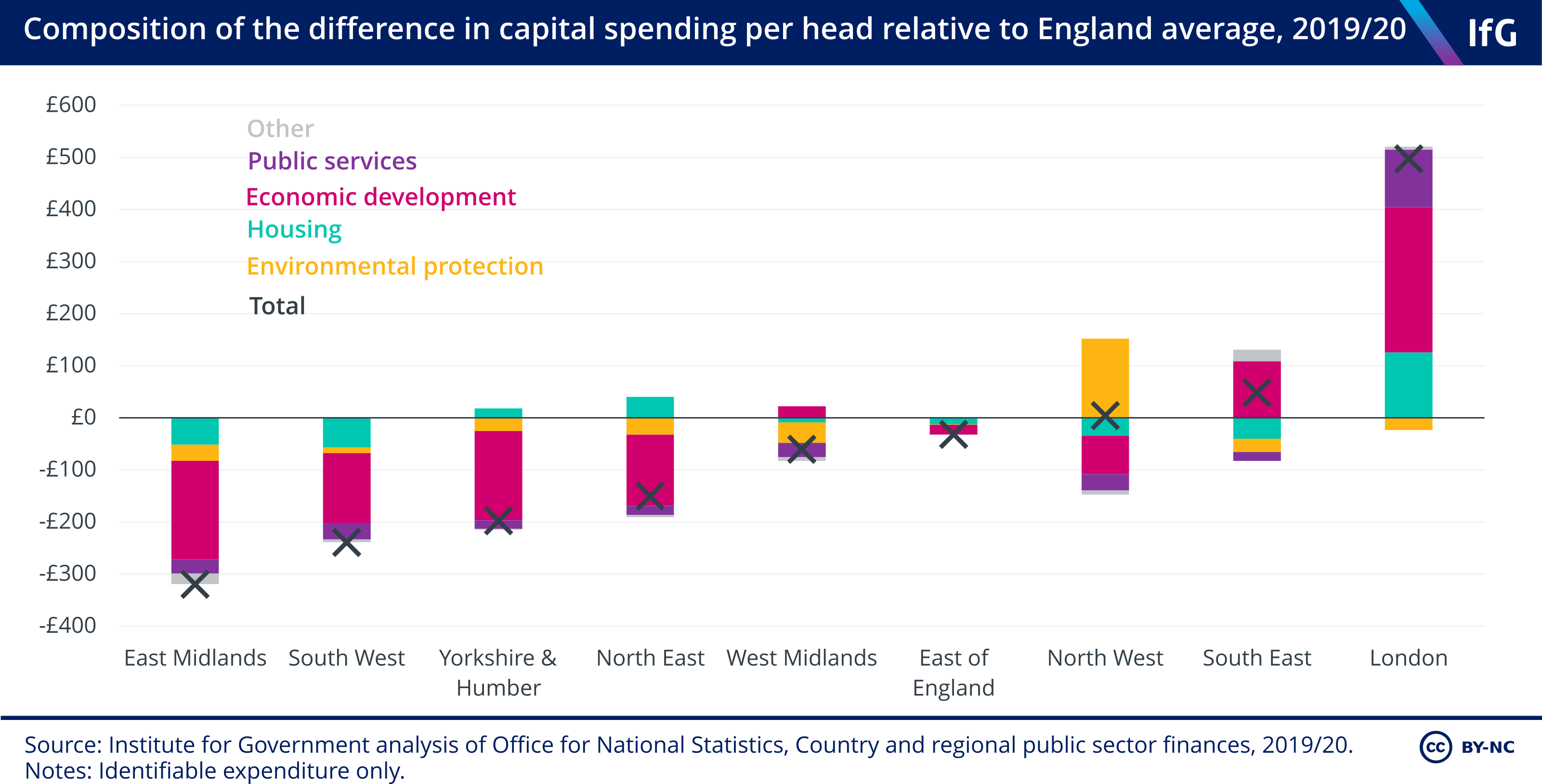

Capital spending

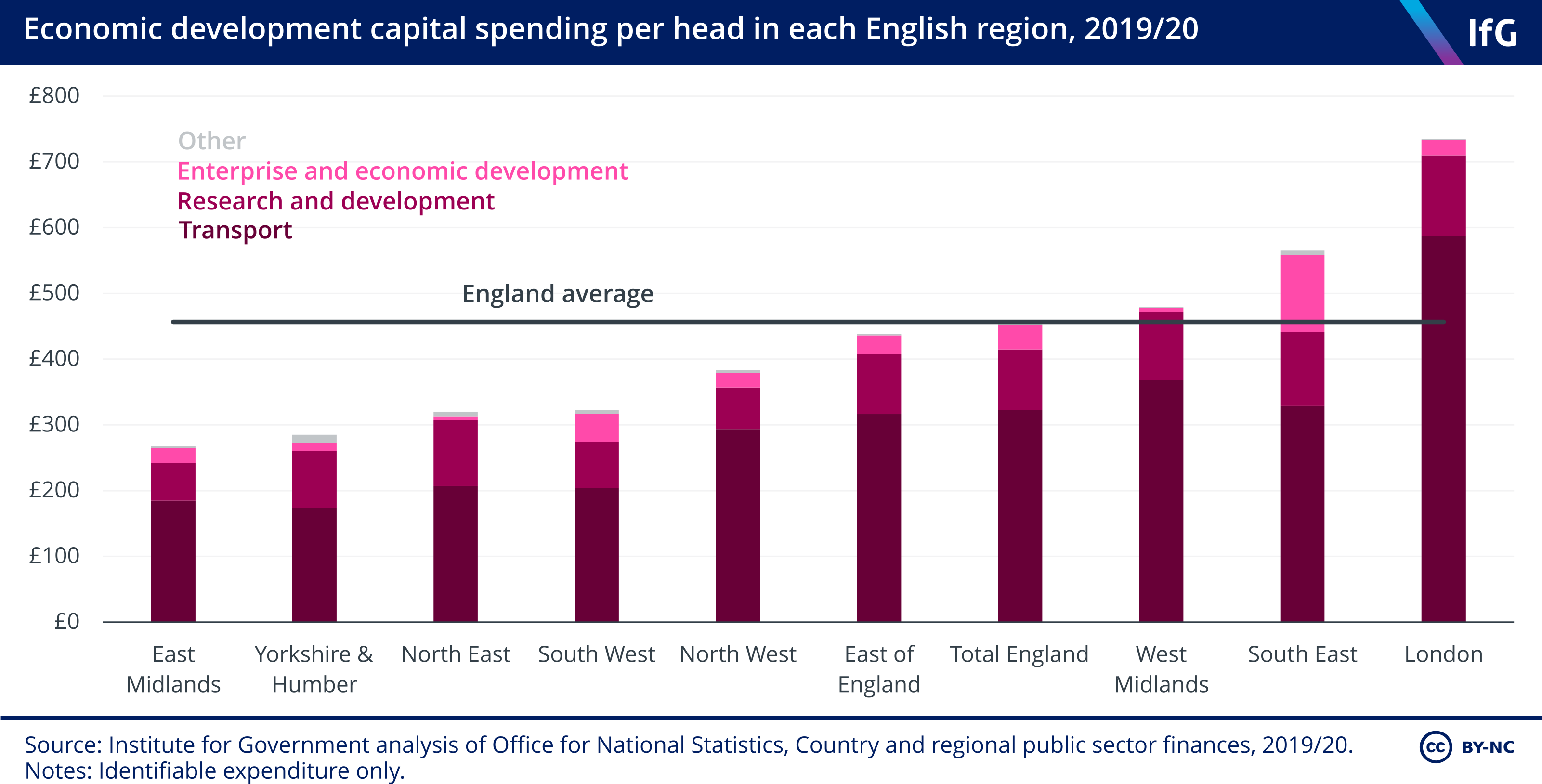

Spending on investment is also higher in London than elsewhere in the UK. The biggest difference is in the ‘economic development’ category, which covers things like R&D and transport.

These areas are core to the government’s levelling up agenda and warrant further attention.

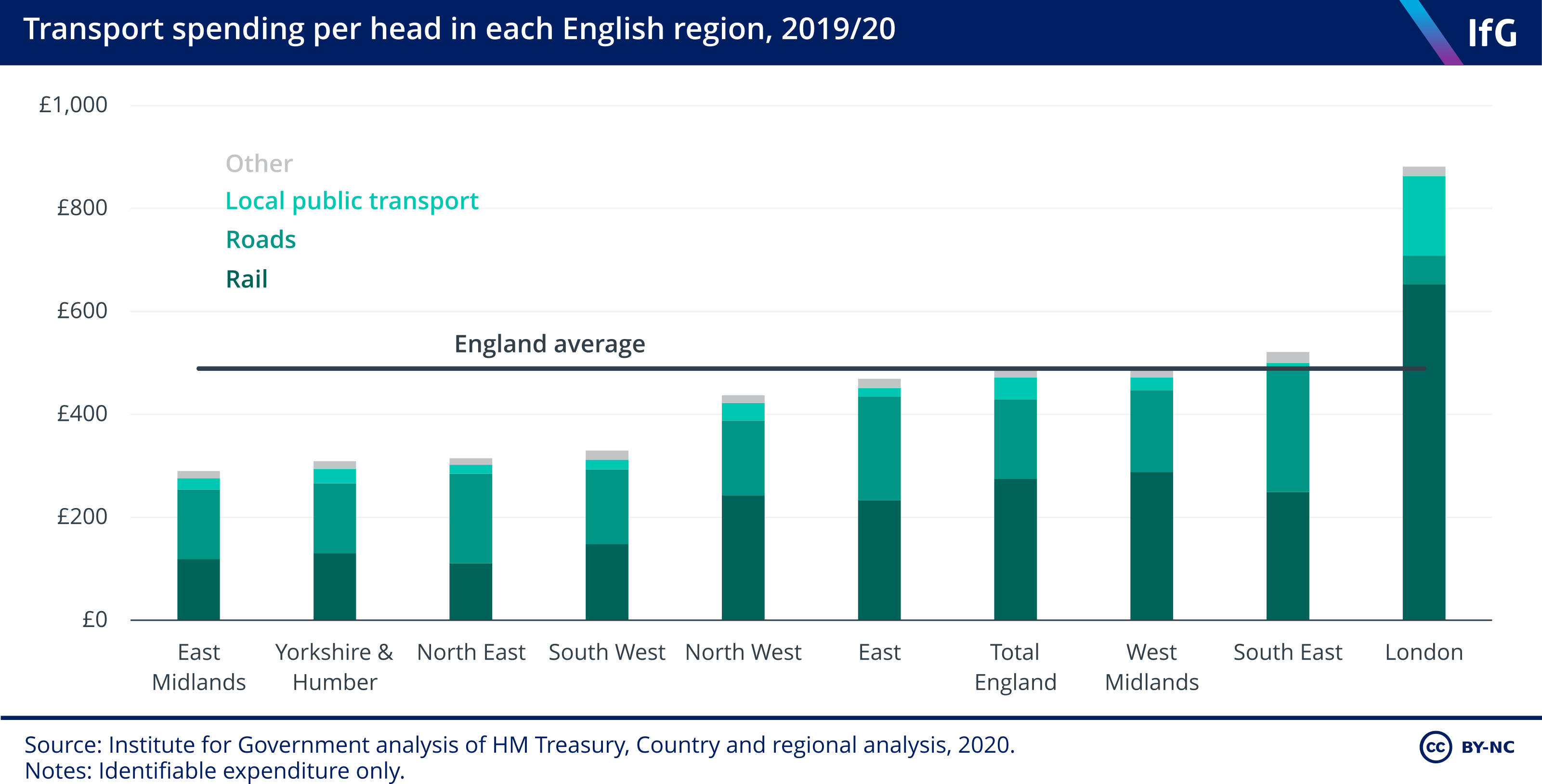

Across England, economic development capital spending is mainly on transport infrastructure investment. This is particularly the case in London, where transport investment makes up most of the additional economic development capital spending compared to the rest of the UK. Government investment in scientific research and development is also more concentrated in London and the South East, which receives 41% of English R&D investment despite containing only 32% of the English population.

Total transport spending in London (including both day-to-day and capital spending) was £882 per person in 2019/20 - £393 per person more than the England-wide average. Most of the difference is accounted for by higher spending on rail and local bus services. This is due to the investment in major projects such as Crossrail as well as the spending by Transport for London on running costs and maintenance from fare revenue, which is higher in London than in other areas due to a more developed existing transport system. The extra spending on London’s transport has led to calls from other regional leaders, for example from Greater Manchester’s Andy Burnham,[4] for ‘London-style’ transport systems in their cities.

Is divergent spending a problem?

Spending more in some areas than others is not necessarily a problem. It is largely inevitable that some areas will receive more or less than the national average of public spending on a per head basis when splitting the country into ten regions. Indeed, the country will look more unequal the further it is broken into smaller sub-divisions, as each locality will have particular features and needs which distinguishes it from the national average – for example areas with more people on Universal Credit will receive more social protection per head.

Furthermore, there may be good reasons for some spending to be higher in London, for example if it makes sense to locate specialist public services close to good transport links.

While spending in London is higher, revenues raised there are much higher too and so it still runs a fiscal surplus while most other regions are in deficit.

However, some of the spending differences may be both symptoms and causes of regional disparities. One of the biggest (and possibly most politically contentious) problems with divergent spending relates to decisions on investment, which as we have shown is higher per head in London and the South-East. In the past, it has sometimes proved easier to gain approval for investment projects in regions with higher productivity as the monetary return on investment can often be higher.

The government has suggested that its levelling up agenda will seek to devote more attention and resource to investment projects in the North of England and Midlands. In late 2020, the Treasury published the findings of its review into the ‘Green Book’, the methodology used to appraise investment decisions to ensure that it was not applied in a way that acts as a barrier to levelling up.[5]

How could data on the geography of spending be improved?

While the data in this explainer already provides some detail about where the government spends money, there are three main ways in which the detail and presentation could be improved.

First, the methodology to allocate spending to different regions could be more rigorous. Some spending is allocated on the basis of an imprecise methodology. For example, several spending streams are allocated based on population or GDP rather than more relevant data that would provide a more accurate allocation.

Second, the published data does not identify the regional split of spending for each department, despite this data already being available. More detail here would allow for a better understanding of the implications of government decisions and make it easier to hold departments to account.

Third, it is only possible to look at the distribution of spending to regions. But interest in geographic inequality also includes smaller areas – such as cities and local authorities. Allocating spending to smaller geographical units would not be easy. Even in cases where it is possible to say which local authority spending occurred in (for example because a hospital is based there), many of the beneficiaries will live in other local authorities. Nonetheless, where it is possible to provide this split it would allow for a more nuanced understanding of which areas are benefiting most from public funds and which are relatively neglected.

* The English population has also increased more quickly over this period, which further exacerbates spending differences.

- Open Innovations, 'Levelling Up With Open Data - Launch', https://open-innovations.org/projects/levelling-up/launch/?utm_source=men_newsletter&utm_campaign=the_northern_agenda_newsletter2&utm_medium=email&pure360.trackingid=dd4f43b5-d851-4f61-ae5d-15b0b492fea1

- Based on central government own expenditure, defined in HM Treasury, Public Expenditure and Statistical Analyses, July 2021, www.gov.uk/government/statistics/public-expenditure-statistical-analyses-2021

- Country and Regional Analysis: November 2021, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1035323/CRA_2021_methodology_notes.xlsx

- Greater Manchester Combined Authority, Greater Manchester asks Government to back early delivery of London-style public transport system, 10 September 2021, www.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk/news/greater-manchester-asks-government-to-back-early-delivery-of-london-style-public-transport-system

- HM Treasury, Green Book Review 2020: Findings and response, November 2020, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/937700/Green_Book_Review_final_report_241120v2.pdf

- Topic

- Public finances Devolution

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Publisher

- Institute for Government