Irish reunification

What is a border poll? What would happen if Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland voted in favour of reunification?

On 3 February 2024, power-sharing in Northern Ireland was restored and Michelle O’Neill of Sinn Féin was appointed First Minister, representing the first time ever that a nationalist politician had held this post. This has led to increased debate about Northern Ireland’s constitutional future and whether a referendum on Irish reunification may now occur.

The Good Friday Agreement (also known as the Belfast Agreement) recognises the right of the people of the island of Ireland to bring about a united Ireland, subject to the consent of both parts. Therefore, in order for Irish reunification to take place, border polls must be held in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

What is a border poll?

A border poll is the term for a referendum on Irish reunification. The first border poll took place in 1973, when voters were asked whether they wanted Northern Ireland to remain part of the UK or be joined with the Republic of Ireland. 99% voted in favour of remaining in the UK. However, the poll was boycotted by most of the nationalist community; turnout was only 59%.

The Good Friday Agreement states that consent for a united Ireland must be “freely and concurrently given” in both the North and the South of the island of Ireland. 49 The Belfast Agreement, available at assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1034123/The_Belfast_Agreement_An_Agreement_Reached_at_the_Multi-Party_Talks_on_Northern_Ireland.pdf#page=3 This is widely interpreted to mean that future border polls must be held in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland at the same time.

How would a border poll be held in Northern Ireland?

As part of the Good Friday Agreement, an explicit provision for holding a Northern Ireland border poll was made in UK law. The Northern Ireland Act 1998 states that “if at any time it appears likely to him that a majority of those voting would express a wish that Northern Ireland should cease to be part of the United Kingdom and form part of a united Ireland”, the Secretary of State shall make an Order in Council enabling a border poll. 50 www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/47/contents

It is not clear exactly what would satisfy this requirement. The Constitution Unit suggests that a consistent majority in opinion polls, a Catholic majority in a census, a nationalist majority in the Northern Ireland Assembly, or a vote by a majority in the Assembly could all be considered evidence of majority support for a united Ireland. 51 www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit/sites/constitution-unit/files/185_a_northern_ireland_border_poll.pdf However, the Secretary of State must ultimately decide whether the condition has been met.

The Order in Council must specify the details of the poll, including the date, franchise, the question and “any other provision about the poll which the Secretary of State thinks expedient”. The referendum would be regulated under the UK’s Political Parties, Election and Referendums Act 2000 and overseen by the UK Electoral Commission, which would have a statutory duty to assess the “intelligibility” of the referendum question. 52 www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2000/41/contents

The legislation stipulates that a secretary of state may not make provision for a border poll within seven years of a previous poll.

How would a border poll be held in the Republic of Ireland?

The Good Friday Agreement does not specify a parallel mechanism for triggering a border poll in the Republic of Ireland. The country’s constitution does however contain a provision for two types of referendum: a constitutional referendum and an ordinary referendum. 53 assets.gov.ie/6523/5d90822b41e94532a63d955ca76fdc72.pdf

A constitutional referendum must be held on any amendment to the constitution, which must first be passed through both chambers of the Oireachtas – Irish Parliament.

An ordinary referendum can be held on a proposed bill if at least half of the members of the upper house and a third of the members of the lower house of Parliament object to the proposal, and the President refuses to sign the bill on this basis.

However, neither of these procedures seem appropriate for a border poll as the Good Friday Agreement implies that it would be held on the principle of reunification, before negotiations take place and a concrete proposal can be put in legislation. It is therefore not entirely clear how a referendum in the Republic of Ireland would be held at this stage.

This is further complicated by the fact that once negotiations for a united Ireland are concluded, implementing the outcome of the negotiations would require a constitutional amendment in the Republic, and therefore another referendum.

Therefore, either two referendums would need to be held: the first an extra-constitutional referendum on the principle of reunification and the second to approve a constitutional amendment. This begs the question of whether two referendums should also be held in the North.

Alternatively, the border polls in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland would need to take place at different times, but this is potentially contrary to the Good Friday Agreement.

What would happen if Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland voted in favour of reunification?

If both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland voted in favour of reunification, the Good Friday Agreement states that it “will be a binding obligation on both governments to introduce and support in their respective parliaments legislation to give effect to that wish”.

Before this can be done, the exact terms of reunification would need to be worked out. One important question would be whether separate arrangements were retained for Northern Ireland, or whether the six counties of Northern Ireland would be fully integrated into the unitary Irish state.

In August 2017, a joint committee of the Irish Parliament suggested that the Northern Ireland Assembly could continue as a devolved regional parliament within Ireland. 54 webarchive.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/implementationofthegoodfridayagreement/jcigfa2016/brexit-and-the-future-of-ireland.pdf

It also suggested that the intergovernmental British-Irish Council could continue, allowing for an ongoing British role in the matters of Northern Ireland to reassure the unionist community.

These recommendations had cross-party support in the committee and built on proposals previously made by the nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) in Northern Ireland.

Who supports a border poll?

Sinn Féin supports holding a border poll; in September 2022, party leader Mary Lou McDonald said that “now is the time” to plan for a border poll, including holding a citizens’ assembly on reunification. 55 The Independent, Sinn Fein leader: Time to plan for border poll on Irish unity, www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/mary-lou-mcdonald-northern-ireland-irish-sinn-fein-simon-coveney-b2173906.html In February 2024, Michelle O’Neill, the new First Minister of Northern Ireland, said she believes a border poll will be carried out in this decade. 56 www.irishnews.com/news/northern-ireland/oneill-expects-poll-on-irish-unity-to-take-place-in-next-decade-EG7MZQKTZVB3PBNYSIAN3P3EZA/

The other major nationalist party, the SDLP, has previously warned against holding a vote before plans on how a united Ireland would work are in place, 57 www.newsletter.co.uk/news/politics/sdlp-leader-colum-eastwood-accuses-sinn-fein-of-shifting-its-position-on-border-poll-issue-1-8956465 though in October 2023 SDLP leader Colum Eastwood was reported as saying that a referendum was likely to occur “towards the end of the decade." 58 BelfastLive, Colum Eastwood says it's SDLP's 'new mission' to 'convince the unconvinced' on a united Ireland, www.belfastlive.co.uk/news/colum-eastwood-says-its-sdlps-27935462

The unionist parties, including the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), oppose a vote on reunification. The 2022 DUP manifesto said a border poll would mean “months and years of arguing and fighting, rather than fixing our health service and […] growing our economy." 59 Democratic Unionist Party, Assembly Election Manifesto 2022, mydup.com/policies/assembly-election-manifesto-2022. DUP leader Jeffrey Donaldson recently rejected predictions of a border poll saying “we are nowhere near a united Ireland”. 60 Irish Examiner, We are nowhere near a united Ireland, DUP leader Donaldson says, www.irishexaminer.com/news/politics/arid-41326510.html Naomi Long, leader of the cross-community Alliance Party, previously said in 2019 she is potentially open to a referendum on Irish unity, but that now is “not the right time.” 61 News Letter, Varadkar and SF split over border poll call, www.newsletter.co.uk/news/varadkar-and-sf-split-over-border-poll-call-109978

In Westminster, the UK Government’s position is that the conditions for a referendum have not been met. 62 www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-44126499 Labour Leader Sir Keir Starmer was reported in October 2023 as saying a referendum on Irish unification was “not even on the horizon” and also said “I don’t think we’re anywhere near that kind of question". 63 BBC News, Irish unity poll not on horizon, says Sir Keir Starmer, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-67020960

The Irish Government has also taken the position that the time is not right for a border poll. In October 2023, Irish Taoiseach (prime minister) Leo Varadkar was reported as saying an Irish unity poll was currently “not a good idea” because it “will be defeated". 64 BBC News, Leo Varadkar says border poll not appropriate at this time, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-62029035

What do the Northern Ireland public think?

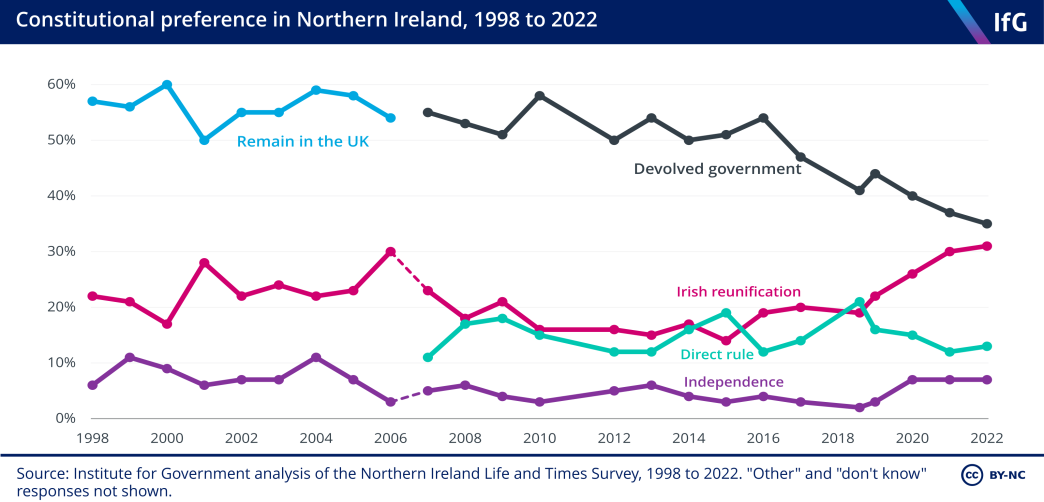

A plurality of Northern Irish voters support the continuing Northern Ireland’s current constitutional position of devolved government within the United Kingdom, although this has fallen from around 55% to around 35%. Support for reunification has risen in recent years and is now the preferred option of 31% of voters as of 2022.

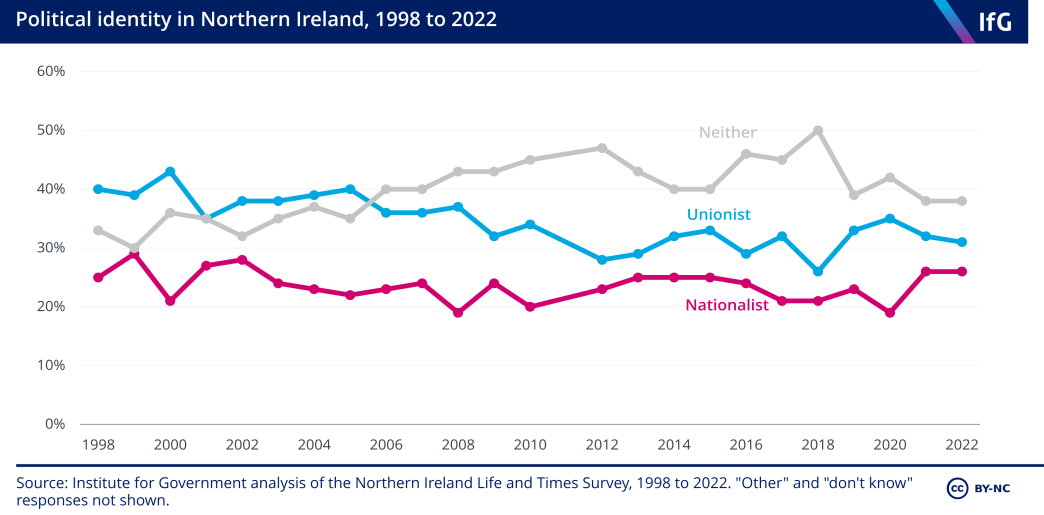

As of 2022, around 40% of Northern Irish adults see themselves as “neither” unionist nor nationalist, up from around 30% in 1998. The proportion of people identifying as nationalist has remained relatively steady at around 20%-25% since 1998.

- Topic

- Brexit Devolution

- Keywords

- Constitutional reform

- United Kingdom

- Northern Ireland

- Publisher

- Institute for Government