This explainer was written before the UK formally left the European Union on 31 January 2020.

There have been 13 national and regional referendums in the UK, but only three of these have been UK-wide: the 1975 and 2016 referendums on EEC/EU membership, and the 2011 on electoral reform.

There are no fixed rules in the UK for when a referendum should take place. Referendums in the UK are held on an ad hoc basis, as and when Parliament decides.

How would a second referendum on Brexit happen?

In order to hold a referendum, Parliament needs to pass primary legislation to provide the legal basis for the vote and to set the question, the franchise (who can vote), the date and the conduct rules for the poll (although the latter two are commonly specified in secondary legislation). So, there will need to be a majority of MPs in favour of both the principle and the practical details of another vote on Brexit.

Currently, the most likely route to a second referendum is if Labour forms a government after the 2019 General Election. The party has pledged to renegotiate a Brexit deal and put that deal to a public vote, if it is elected to government. The SNP, Liberal Democrats, Plaid Cymru and the Green Party are also in favour of a second referendum, and so would likely support referendum legislation if Labour did not have a majority in the Commons.

Prior to Parliament being dissolved, MPs were planning to attempt to amend the legislation required to implement the government’s Brexit deal – the Withdrawal Agreement Bill – to require the government to hold a “confirmatory referendum” before ratifying it. If the Conservative Party forms a government after the election this remains another possible route to a second referendum, but only if a majority of MPs are in favour of it.

But any legislation enabling a referendum would also require a minister to table a motion to authorise spending to cover the cost of holding the vote, so a further referendum on Brexit would almost certainly require support from the government of the day.

When could a second Brexit referendum be held?

The Act enabling the 2016 referendum spent seven months in Parliament, but there was little urgency. A bill enabling a referendum could be passed much more quickly.

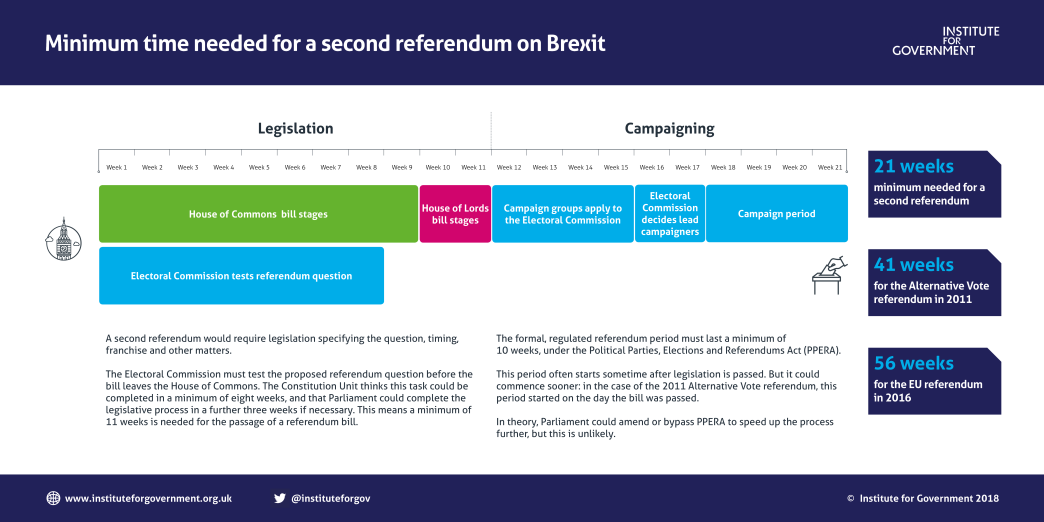

The biggest constraint on how quickly a referendum bill could be past is question testing. The Electoral Commission has a statutory duty to test the “intelligibility” of any referendum question proposed in a bill introduced into Parliament. This process usually takes up to 12 weeks but could be curtailed; the Constitution Unit suggests this process could be completed in a minimum of eight weeks.

The Electoral Commission will need to report to Parliament before the bill has passed its final amending stage, so that it will have the opportunity to change the question in accordance with the commission’s recommendation. The Constitution Unit estimates that Parliament could complete the other legislative stages both before and after testing in three weeks; an estimated total of 11 weeks minimum to pass legislation.

Once legislation is passed, there will need to be time for the referendum campaign. The minimum statutory regulated referendum period is 10 weeks, under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act (PPERA) – this comprises six weeks for designating lead campaigners for each side of the debate, and four weeks for campaigning. However, in practice the regulated period has usually been longer, or the process of designating lead campaigners has taken place before the start of the regulated period so that they have a full 10 weeks to campaign.

A fair estimate is that the whole process would take a minimum of 21 weeks, but this would be much shorter than other recent referendums.

The leader of the Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn, has said that Labour would negotiate a new deal with the EU within three months and hold a referendum within six months of a Labour government taking office. This would require a ‘twin-track’ approach in which the legislation would need to be introduced before the deal is agreed.

What might the referendum question(s) be?

Most referendums offer voters a binary choice between two options. In the case of Brexit, there are a number of possible outcomes: leaving with a deal – with a number of alternative deals on offer, leaving with no deal or remaining in the EU.

A second Brexit referendum could offer a binary choice between any two of these options. Labour has said it will offer a choice between a ‘credible Leave option’, a new deal which it will negotiate, and Remain. However, Labour’s deal will likely involve a closer relationship the EU than many proponents of Brexit would like. This approach would be opposed by those who support Boris Johnson’s deal or no deal. MPs may seek to amend the legislation to add an additional option – although, of course, they will require a majority in Parliament to do so.

If a referendum were held that includes all three options then there are different ways to determine the result. The simplest approach would be to allow each voter to vote for their favoured option, with the most popular choice declared the victor. This could lead, however, to an option being implemented without support of a majority of voters.

To avoid this, voters could rank their choices in order of preference. The least popular first choice would be eliminated, and its votes reallocated based on second preferences. This would ensure that the successful option gained over 50% of first and second preferences.

Finally, the referendum could include two separate questions. Question 1 could ask whether voters wish to Leave or Remain, as in 2016. Question 2 could ask voters to select between the two different models of Brexit, if there is still a pro-Leave majority.

Who would campaign in a second referendum?

Any UK-based groups or individual can campaign in a referendum; campaigners wishing to spend more than £10,000 during the regulated referendum period must register with the Electoral Commission.

The Electoral Commission also has the responsibility of designating a lead campaign group for each referendum outcome. The official campaigns are entitled to certain benefits including public funding, higher spending limits, free campaign broadcasts and free postage of campaign materials.

Political parties can also campaign in a referendum—and are entitled to higher spending limits than other campaign groups—but they must submit a declaration stating which outcome they propose to campaign for.

The Labour Party has said it will decide which side of the campaign, if any, to back in referendum through a ‘one-day special conference’. While the Liberal Democrats, the SNP, Plaid Cymru and the Green Party are all likely to support a Remain option in a second referendum, the Conservative and Brexit parties’ support for Leave may depend on the deal on offer.

Who would be entitled to vote in a second referendum?

In the 2016 EU referendum, the UK parliamentary franchise was used. This meant UK, Irish and Commonwealth citizens age18 years and above and resident in the UK were entitled to vote, along with UK citizens living abroad for less than 15 years.

There are currently about 46 million registered voters for UK parliamentary elections, and an estimated sic million people who are eligible but not registered.

Unlike elections in the UK, there is no standing franchise for referendums in the UK. Legislation for a second referendum would need to specify who can vote. Labour has previously pledged to amend the electoral franchise to 16- and 17-year olds, and EU citizens, and so a Labour government may seek to extend the franchise for a second referendum on Brexit. However, concerns have been raised that if the result of the 2016 referendum is overturned on the basis of a different franchise, many Brexit supporters may question the legitimacy of the vote.

There are an estimated 2.6 million EU citizen adults in the UK, 3 million ineligible UK expats, and 1.5 million 16- and 17-year olds living in the UK.