Devolution: common frameworks and Brexit

What happens to powers being ‘repatriated’ from the EU after Brexit?

How will Brexit affect the powers of the devolved institutions?

When the Brexit transition period ends, subject to the terms of our future relationship with Brussels, powers exercised at EU level will be ‘repatriated’ to the UK.

Many of these powers, for instance, those relating to immigration, trade and competition policy, will become the sole preserve of Westminster.

In other areas, where EU law intersects with the legislative competence of the devolved institutions, powers currently exercised by EU institutions will transfer to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

However, the UK and devolved governments have agreed[1] that in some areas new UK-wide ‘common frameworks’ will be needed to ensure consistency or co-ordination across certain policies.

What are ‘common frameworks’?

The devolved institutions are legally bound to comply with EU law and will continue to be until the end of the transition period. As a result, in many nominally devolved policy areas, the autonomy of the devolved institutions is significantly constrained in practice.

When the transition period ends, these policy areas will return to devolved control.

This could lead to policy differentiation within the UK in areas where EU law has previously provided a common legal framework.

To prevent or limit divergence, common frameworks may therefore be created to "set out a common UK, or GB, approach and how it will be operated and governed". Depending upon the policy area, "this may consist of common goals, minimum or maximum standards, harmonisation, limits on action, or mutual recognition".[2]

What principles will guide the development of common frameworks?

On 16 October 2017, the UK and devolved governments announced that they had "agreed the principles"[4] that will guide the development of common frameworks, including six different reasons for why common frameworks might be needed:

- To “enable the functioning of the UK internal market”

- To “ensure compliance with international obligations”

- To “ensure the UK can negotiate, enter into and implement new trade agreements and international treaties”

- To enable the “management of common resources”

- To “administer and provide access to justice in cases with a cross-border element”

- To “safeguard the security of the UK”.

The UK government reiterated its commitment that frameworks will “respect the devolution settlements" and will therefore be “based on established conventions and practices” including the Sewel convention.

The UK and devolved governments also agreed that the overall effect will deliver “a significant increase in decision-making powers for the devolved administrations”, and that no existing devolved policy power will be taken away.

In what areas might common frameworks be created?

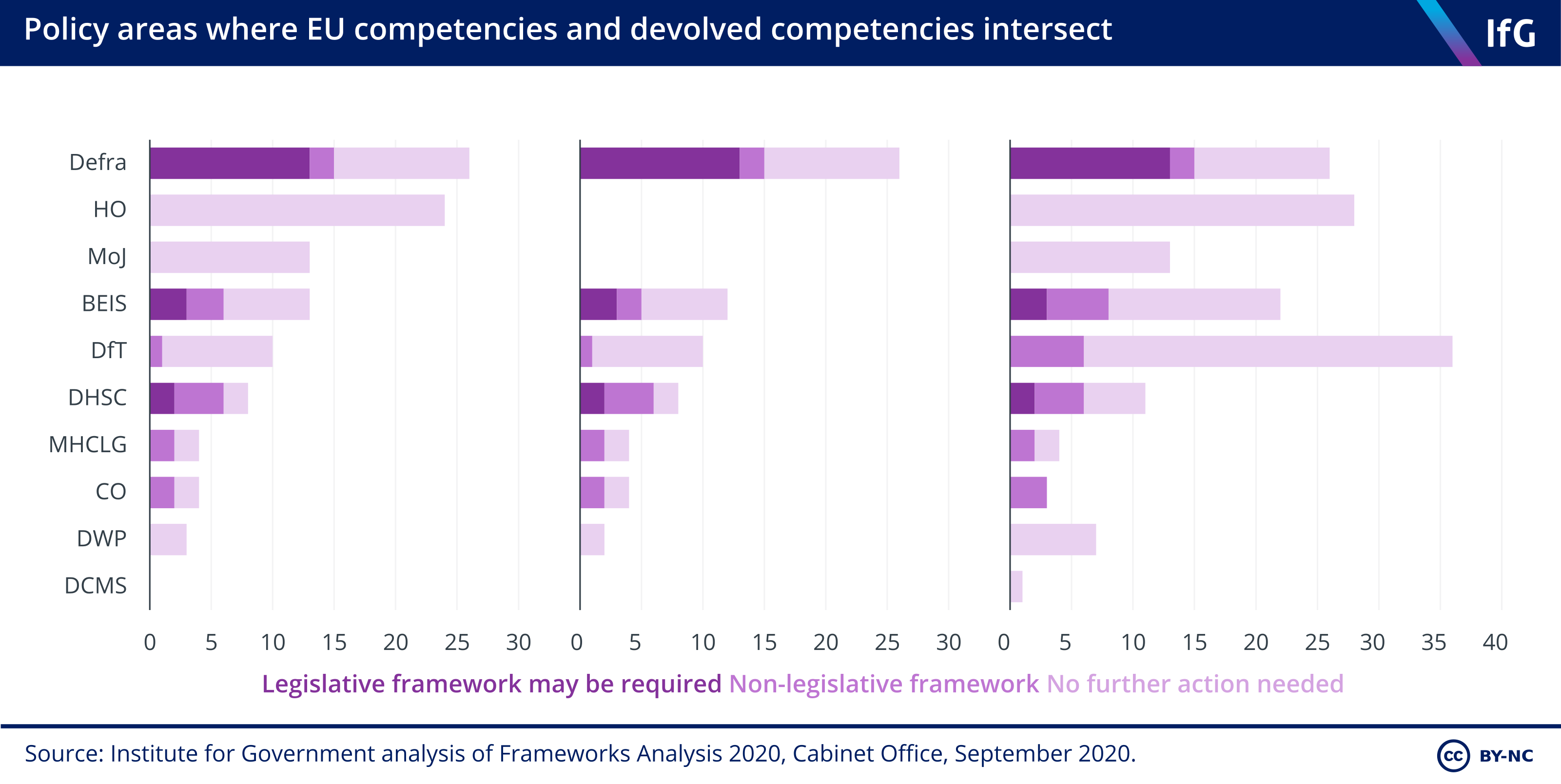

According to the UK government[3], there are 154 distinct policy areas where EU law intersects with devolved powers in at least one of the three devolved nations. These include environmental regulation, agriculture, food standards, animal welfare, public procurement and aspects of justice, transport, and energy.

The government departments with the greatest number of policy areas falling into this category are the Department for Transport (DfT – 38 areas); the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra – 26 areas); the Home Office (28 areas); and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS – 22 areas).

However, new frameworks will not be required in all these policy areas. The UK government believes that frameworks should be developed to replace EU law in just 40 of these areas.

What form might the new common frameworks take?

In its updated frameworks analysis[5], published in September 2020 , the UK government, following close consultation with the devolved administrations, categorised the 154 policy areas where EU and devolved powers intersect into three groups:

Category 1: “No further action areas”, where the four governments will continue to cooperate but there is no need to create a framework. There are 115 such areas in the latest analysis. This marks an increase from the 63 identified in April 2019. In these areas each government will be free to set its own policy.

Category 2: Non-legislative areas, where co-ordination is required, but a binding legal framework is seen as unnecessary. There are 22 such areas in the latest analysis, down from 78 in April 2019. In these areas, powers will be repatriated to the devolved institutions but with agreement about how the different governments will work together, for instance through concordats or memoranda of understanding agreed between ministers. In some of these areas retained EU law will continue to provide a consistent legal framework across the UK .

Category 3: Legislative areas, where regulatory consistency is deemed crucial, and new frameworks could be established through legislation passed at Westminster for the entire UK. There are 18 areas where the government analysis believes “legislative common frameworks arrangements might be needed, in whole or in part”.[6]

Most of these areas fall within Defra’s remit, including subsidies for agriculture, regulation of genetically modified organisms, animal health and welfare, chemical use in agriculture, and the management of fisheries. Legislative frameworks are also envisaged for food safety standards, services regulation, emissions trading and mutual recognition of professional qualifications.

This chart was first published in the Institute for Government’s report on Devolution at 20

What does the EU Withdrawal Act mean for common frameworks?

The EU Withdrawal Act 2018 will end the authority of EU law in the UK and convert EU law, as it stood on the moment of exit, into UK law at the end of the transition period on 31 December 2020.

Section 12[7] of the EU Withdrawal Act provides that control of areas where EU and devolved law overlap will pass by default to the devolved institutions when the transition period ends.

However, it also allows UK ministers to freeze the devolved governments’ ability to legislate in those areas where it believes legislative common frameworks will be needed. In any area where this power were used, the UK government would be able to set UK-wide regulations until new common frameworks were agreed.

Ministers have to consult with their devolved counterparts, and report to the UK parliament every three months on where and why they have made such regulations, and on the progress made towards agreement on new UK-wide frameworks.

So far, the Section 12 “freezing” power has not been used by UK ministers. Instead, the UK and devolved governments have sought to reach agreement on the terms of new frameworks.

What progress has been made in developing the new common frameworks?

There has been substantial intergovernmental working on common frameworks, mainly at civil service level. In 2018, over 30 ‘deep dive’ workshops were held, each bringing together civil servants from different administrations to discuss common frameworks for a specific policy area, and on cross-cutting themes such as the UK internal market. In 2019, these continued alongside two joint UK government/devolved administration Project Board meetings and stakeholder engagement events.

The EU Withdrawal Act requires the UK government to publish quarterly progress reports[8] on common framework development. The eighth of these was published in September 2020.[9]

The delivery plan for common frameworks has five phases:

- Principles and proof of concept

- Policy development

- Review and consultation

- Preparation and implementation

- Post-implementation

However, the coronavirus crisis has placed significant capacity constraints on the UK and devolved governments. As a result , the most recent progress report stated that it would no longer be possible to deliver all the frameworks fully by the end of the transition period. The four governments now expect to deliver provisional frameworks – outline documents and accompanying concordats – by the end of 2020. Work will continue into 2021 to develop full frameworks.

How does the UK Internal Market Bill affect the development of common frameworks?

The development of common frameworks has been complicated by the UK Internal Market Bill, which the government introduced in September.

If passed as introduced, this bill would enshrine a “market access” commitment in law, which would ensure that anything that is acceptable for sale in one part of the UK will be acceptable in all other, and prevents governments from prioritising local businesses over those from elsewhere in the UK. This legislation will cut across many of the areas where common frameworks are due to be developed. It is not clear how the bill and the frameworks are intended to function alongside each other.

The Scottish and Welsh governments strongly oppose the bill, which they argue would allow goods produced elsewhere in the UK to undercut local standards and would therefore unduly constrain their ability to implement their policy aims. The Scottish economy secretary, Fiona Hislop, has said the bill will “undermine the good progress made on common frameworks”; this strained political context may cause further delays.

- Joint Ministerial Committee communiqué: 16 October 2017, GOV.UK, 16 October 2017, retrieved on 16 March 2020, www.gov.uk/government/publications/joint-ministerial-committee-communique-16-october-2017

- Ibid.

- Cabinet Office, Revised Frameworks Analysis: Breakdown of areas of EU law that intersect with devolved competence in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, GOV.UK, April 2019, retrieved on 16 March 2020, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/792738/20190404-FrameworksAnalysis.pdf

- Joint Ministerial Committee (EU Negotiations) Communique, 16 October 2017, retrieved on 16 March 2020, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/652285/Joint_Ministerial_Committee_communique.pdf

- Cabinet Office, Revised Frameworks Analysis: Breakdown of areas of EU law that intersect with devolved competence in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, GOV.UK, April 2019, retrieved on 16 March 2020, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/792738/20190404-FrameworksAnalysis.pdf

- Cabinet Office, Frameworks Analysis, GOV.UK, 9 April 2018, retrieved on 16 March 2020, www.gov.uk/government/publications/frameworks-analysis

- European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, Section 12, legislation.gov.uk, www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2018/16/section/12/enacted

- Cabinet Office, The European Union (Withdrawal) Act and Common Frameworks: 26 September 2018 to 25 December 2018, February 2019, retrieved on 16 March 2020, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/788764/CCS207_EUWithdrawalActAndCommonFrameworks.pdf

- Cabinet Office, The European Union (Withdrawal) Act and Common Frameworks: 26 June 2019 to 25 September 2019, October 2019, retrieved on 16 March 2020, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/841824/The_European_Union__Withdrawal__Web_Accessible.pdf

- Topic

- Brexit Devolution