A low-key year in Parliament, but it's not all Brexit's fault

The Government’s status as a minority—and Brexit—has significantly curtailed its legislative programme.

The EU Withdrawal Bill finally finished its parliamentary journey last week. Dr Alice Lilly looks at what else has been happening in Parliament in the past year, and finds the Government’s status as a minority—and Brexit—has significantly curtailed its legislative programme.

Halfway through the unusual two year parliamentary session—only the second since 1945— the Government has introduced 35 bills, of which 19, or more than half, have received Royal Assent. By comparison, by the end of the last two-year session in 2010/12, the Government had introduced and received Royal Assent for a total of 47 bills.

The total numbers may be roughly comparable – but the legislation that has made it through is not the kind you would expect from a Government in its first session of a new Parliament.

Normally, a new government would introduce major bills around key manifesto promises. Instead, key manifesto pledges—like creating new grammar schools—were conspicuously absent from the Queen’s Speech. And since this session began, we have instead seen routine financial legislation (two Finance Bills and two Estimates bills), urgent Northern Ireland legislation, and bills dealing with relatively minor policy areas (the Data Protection Act, Space Industry Act and the Financial Guidance and Claims Act).

This is not surprising. Recognising the difficulty of legislating without a built-in majority in the Commons, and the need to store political capital around Brexit, the Government’s strategy has been to avoid even the faintest possibility of defeat. Ministers have reportedly been discouraged from using legislation to implement their policies; and where legislation has been introduced, the Government has had to broker various eleventh-hour compromises.

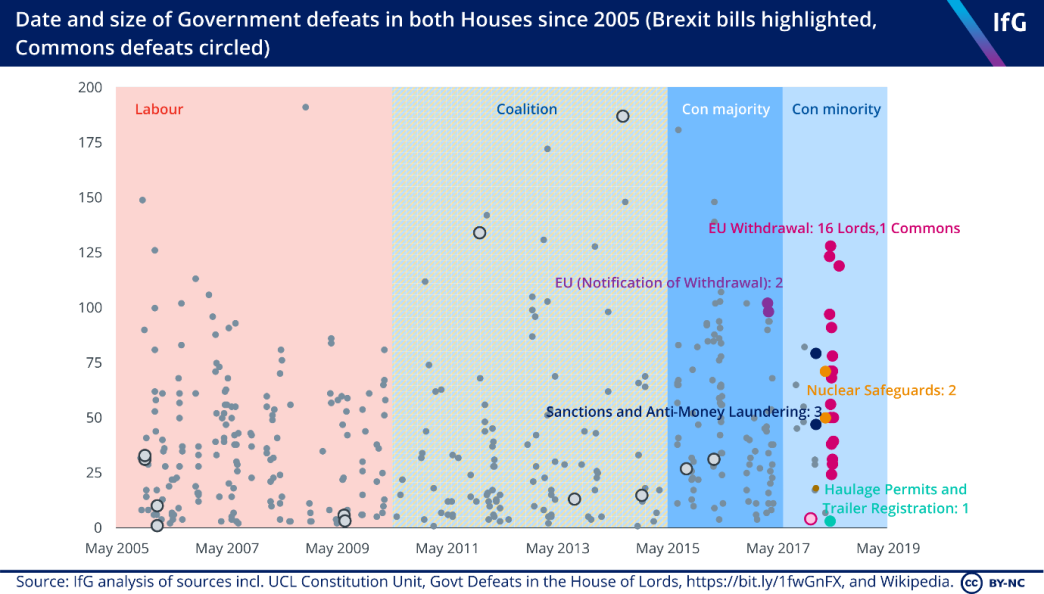

This strategy is working so far—at least in the Commons, where the Government has only been defeated once, on an amendment to the Withdrawal Bill. In the Lords, the story has been different, with Government defeated 32 times in the last year, including 16 times on the Withdrawal Bill.

But this is not unusual. Lords defeats are always more common for all governments, given the lack of in-built government majorities in the Upper Chamber: between 1999 and 2010, governments were defeated over 450 times in the Lords.

Progress on Brexit legislation is still too slow

The need to avoid defeats has shaped the Government’s approach to Brexit legislation. In the Queen’s Speech, the Government announced plans for eight Brexit bills—since then, it has announced a further four, including the Withdrawal and Implementation Bill.

But progress continues to be too slow:

- White papers on fisheries and migration have yet to appear;

- Only one bill of the twelve (the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act) has received Royal Assent;

- The Nuclear Safeguards Bill and EU Withdrawal Bill are waiting for Royal Assent, with the latter having taken over 270 hours in both Houses.

Meanwhile, Government has been delaying other Brexit legislation to try and stave off crunch votes on the Customs and Trade Bills. Neither have reached report stage in the Commons, despite having completed committee stage in early February.

These delays, combined with the hard March 2019 deadline for much of this legislation to be in place, risk creating a pile-up in Parliament this autumn.

IfG will be exploring what the data tells us about how effectively Parliament is fulfilling its role in a new project, Parliamentary Monitor, the first edition of which will be published in September.

- Administration

- May government

- Legislature

- House of Commons House of Lords

- Tracker

- Parliamentary Monitor

- Publisher

- Institute for Government