Jeremy Hunt will not find it easy to deliver departmental spending cuts

It will be difficult to find cuts to public service budgets

The new chancellor has said that spending will not increase as quickly as previously planned, but Thomas Pope argues that it will be difficult to find cuts to public service budgets

In less than 72 hours after becoming chancellor, Jeremy Hunt has signalled a radical shift – both of policy and tone – in this government’s economic policy. He has now cancelled almost all measures in Kwasi Kwarteng’s 23 September mini-budget, but even that £32 billion reversal does not appear to be enough to get the public finances on a sustainable path. On Monday morning Hunt said that “all departments will need to redouble their efforts to find savings and some areas of spending will need to be cut”.

Given his commitment to prioritise the vulnerable when making these decisions, and the large cuts needed to get debt falling according to media reports [1], Hunt will not be able to find all or most of these savings from the welfare budget. But as the Institute for Government’s and CIPFA’s Performance Tracker, published today, highlights, cutting departments’ spending on public services and investment will be difficult too. After 12 years of tight settlements and falling budgets, Hunt should not expect to find much in the way of ‘efficiencies’. Any cuts to departmental spending will require difficult choices that will impact on service scope and quality or – if he goes after investment budgets instead – undermine the government’s prioritisation of growth.

Public services are reeling from the dual shocks of austerity and covid

Performance Tracker lays bare the challenges facing public services. Services entered the pandemic in a vulnerable position, with eight of the nine services we study performing at least somewhat worse on the eve of the pandemic than they were in 2010 – before 10 years of spending restraint kicked in. The pandemic worsened their position considerably. Almost all public services were disrupted, most obviously health and social care but also schools, courts and prisons that closed or amended their working patterns in response. Less activity then means even larger backlogs now: the backlog of elective care in the hospitals is still rising and the crown court backlog has doubled on a like-for-like basis since covid. That means longer waiting times and worse outcomes.

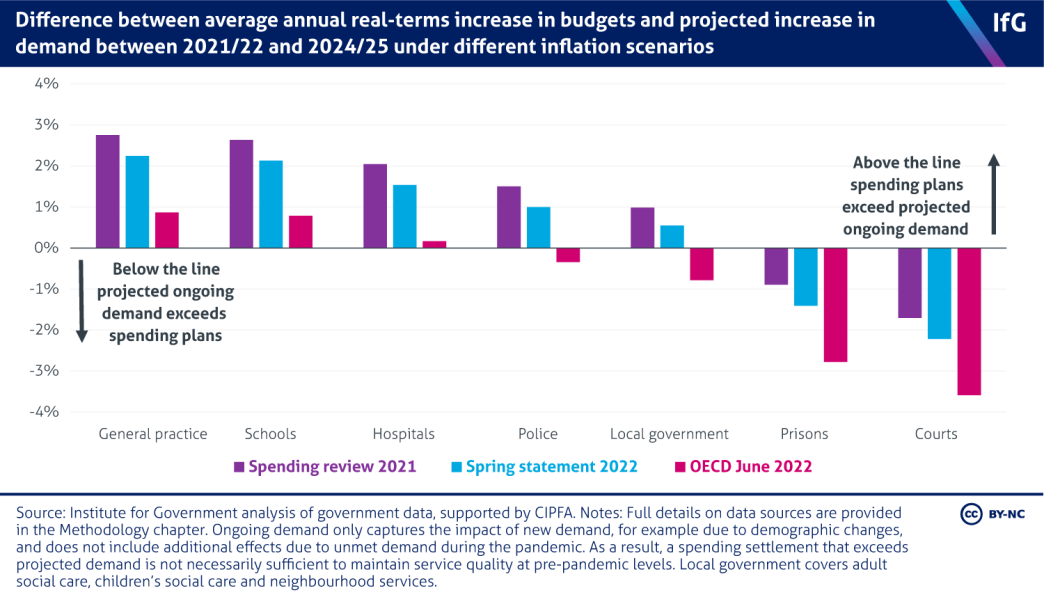

The 2021 spending review, which set budgets up to 2024/25, was relatively generous when announced. But inflation is now expected to be much higher, eroding the generosity of those cash plans. In October 2021, services expected real increases of 3.3% per year: we now expect spending power of services to increase by only 1.5% per year. Much of the additional cost will be from higher public sector pay. That has risen less quickly this year than inflation and private sector pay but still faster than planned last October. Many services are already unable to recruit and retain enough workers, so holding down pay is unlikely to be a viable option.

Overall, our analysis finds that spending plans over the next three years will not even be enough to meet ongoing demand or to deal with the legacy of the pandemic. Any easy-win efficiencies will have been found long ago. The equation is inevitable: less money will mean worse public services.

Announcing cuts beyond the spending review period would not be credible

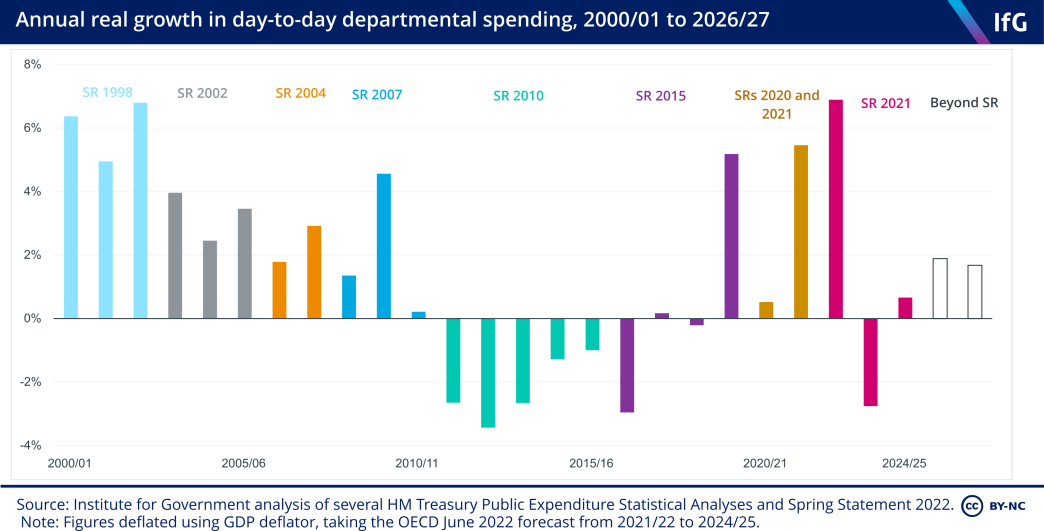

The government has indicated that it wants debt to start falling relative to national income by the middle of the decade. That is beyond the end of the current spending review period, meaning the chancellor could pencil in cuts to day-to-day spending beyond 2024/25 to help meet this objective. Current plans imply that element of spending rising by 2% per year in real terms over thart period.

However, markets and voters might rightly be sceptical about such an announcement, which does not require the chancellor to specify which services will see cuts and means no decision would need to be taken until after the next election. Recent history suggests these ‘pencilled in’ cuts would be unlikely to materialise. Six months before each of the 2015 spending review, the 2019 spending round and the 2021 spending review, the government was pencilling in very tight spending plans. When it came to making the difficult decisions allocating money to departments, George Osborne, Sajid Javid and Rishi Sunak all found tens of billions of pounds extra each year to make things easier. Hunt’s predecessors were able to announce these unlikely spending paths while retaining broad fiscal credibility with markets and the public, but the current chancellor is unlikely to have this luxury given the government’s actions in the last few weeks.

Capital spending could be cut, but it will be hard to reconcile with prioritising growth

Given how difficult it will be for Hunt to announce credible cuts to day-to-day spending, he may be looking to the government capital (investment) budget instead. Public sector net investment is currently expected to be maintained at 2.5% of GDP, which would be a high level relative to the last 30 years or so. The impact of cuts to capital spending – which result in a gradual erosion of the quality of infrastructure – also take longer to become apparent to the public than cuts to day-to-day spending. Both these factors could make investment spending an attractive option for cuts.

However, a look at how the government’s capital budget is spent shows that there are difficult choices here too. It will be difficult to cut defence spending, given Truss’s commitments on this front, and Performance Tracker has highlighted how a lack of capital spending in those areas means many public services are operating in dilapidated buildings which also affect their day-to-day operational efficiency. That would leave Transport and Business (mostly R&D) as the big capital budgets to cut, but while such cuts are feasible these budgets could both, if spent well, contribute to economic growth – making cuts here difficult to reconcile with the government’s flagship aim.

There are no easy choices on spending and few easy-win ‘efficiencies’ to be found. If Jeremy Hunt is determined to balance the books by reducing departmental spending plans, he will need to decide – and should explain – which public services will perform worse as a result and which growth-enhancing capital projects will be dropped.

___________________________

- Supporting document

- Performance Tracker 2022 (PDF, 4.44 MB)

- Position

- Chancellor of the exchequer

- Department

- HM Treasury

- Public figures

- Jeremy Hunt

- Publisher

- Institute for Government