Hypothecated tax is no long-term solution for funding health and social care

A one-off tax to fund health and social care might solve the short-term problem but would do nothing more than kick the problem down the road.

The idea of a ‘hypothecated’ tax, raised specifically to pay for the NHS, is gaining increasing support. Gemma Tetlow argues that hypothecation is no substitute for a long-term, cross-party solution to the issue of how to fund health and social care.

Hypothecated taxes – ones whose revenues are earmarked for a specific purpose – used to be derided by tax policy experts inside and outside government.

But support has bubbled up over the past year, as politicians and experts have grappled with how to fund long-term health and social care spending pressures.

There are rumours that Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt supports of the idea of ring-fencing National Insurance (NI) contributions for this purpose. A cross-party group of parliamentarians who are advocating this course told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme that doing so could be a “second Beveridge moment” – referring to William Beveridge’s 1942 report that laid the groundwork for the post-war introduction of the NHS and welfare state.

"This has to be a new platform for the NHS and social care that can last a generation or two and we urge everyone to seize it,” said Conservative MP Nick Boles.

There is a pressing need to break out of the recent cycle of “crisis, cash, repeat” that the Institute for Government/CIPFA Performance Tracker has highlighted.

But hypothecating NI revenues would not provide a long-term solution. What is needed is cross-party agreement on the scale and scope of health and social care services that the public sector should fund, and an honest discussion of the spending, tax and borrowing implications.

A hypothecated tax is either undesirable or deceiving

Hypothecated taxes are usually a bad idea and the Treasury remains opposed.

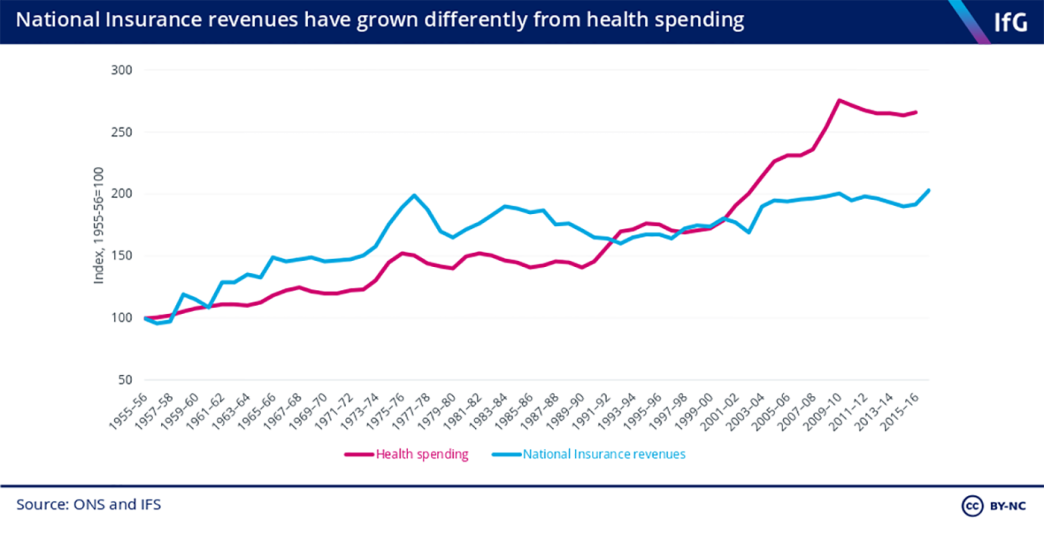

If the revenues from the tax really are used solely to fund a particular activity, spending on that service will fluctuate in an uncertain way as revenues go up and down through the economic cycle. Spending will rise over the long term only as fast as the tax base. These patterns are unlikely to match changes in demand for public services; this is shown in the chart below, which compares past spending on the NHS for the delivery of health care with the level of NI receipts.

If instead politicians retain control of overall spending levels – and top up the tax revenues or allocate them elsewhere as they see fit – then hypothecation is no more than a convenient mirage to help sell tax rises to a sceptical public. Gordon Brown’s 1 percentage point increase in NI in 2002 to provide “significant increases in resources for the National Health Service” was just such an illusion.

National Insurance is a particularly bad tax

NI is the tax most often suggested for hypothecating to fund health and long-term care. Part of the NI fund already notionally funds the NHS.

But this tax has specific problems. It is levied only on earned income, not on other income such as from investments or pensions. Raising additional revenues from this source would do more to discourage people from working than would raising additional revenue from, say, income tax.

NI is also regressive, with the marginal tax rate being lower on those with higher earnings.

It is best to look at the tax system as a whole when thinking about how to raise additional revenues. There is a risk that hypothecating specific revenues to fund health care would make sensible tax reform of the kind argued for by the Institute for Government more difficult.

But it could be a politically expedient way of raising revenues

Despite these problems, former critics have started to soften to the idea as a way of raising revenues for health and social care.

Nick Macpherson, former permanent secretary to the Treasury, opposed hypothecation while a civil servant but has now spoken out in favour. Others are also reluctantly considering the idea.

Mr Hunt believes the idea would be saleable to the public. Survey data suggests he is right: members of the public are more willing to support a tax rise if it is specifically earmarked for the NHS.

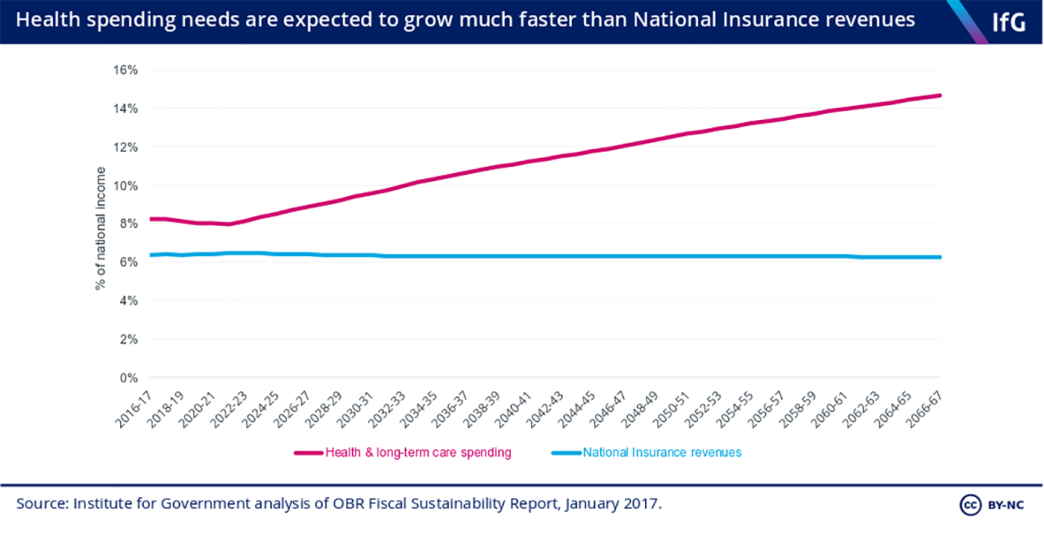

The problem is that revenues from NI – and most other major taxes – are forecast to grow roughly in line with the economy in coming years. In contrast, as the chart below shows, demands for health and social care spending are expected to grow much more rapidly, as the population ages.

A one-off increase in tax, hypothecated to fund health and social care, might solve the short-term problem but would do nothing more than kick the problem down the road.

To ensure stable long-term funding for health and social care, there needs to be cross-party support for a shared vision of the scale and scope of these services to be funded by the state, and an honest debate about the tax and borrowing implications of that.

If this were achieved, it really could be a “second Beveridge moment”.

- Keywords

- Tax NHS Health Social care Public spending

- Position

- Health secretary

- Public figures

- Jeremy Hunt

- Publisher

- Institute for Government