A coronavirus testing target is only valuable if it is part of a wider exit strategy

Increasing coronavirus testing capacity is useful, but the target will only be of value if is part of a wider exit strategy

Increasing coronavirus testing capacity is useful, but Nick Davies argues that the testing target will only be of value if is part of a wider exit strategy

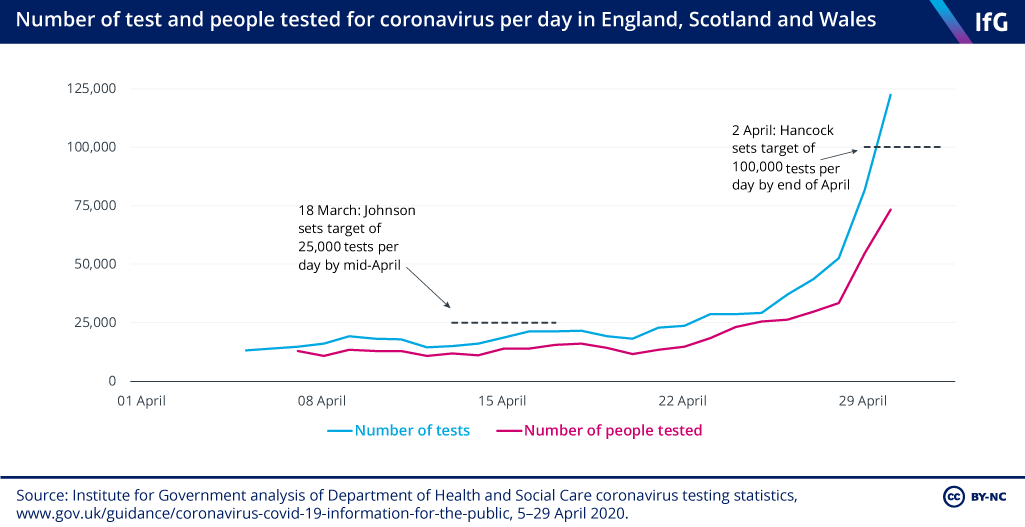

A testing target has been a daily feature of the government’s press conferences since the coronavirus outbreak. The first target was a vague one. On 25 March, Boris Johnson declared that coronavirus testing capacity would be increased to 250,000 tests per day ‘hopefully very soon’. One week later, health secretary Matt Hancock revised that target down to 100,000 tests per day but set a hard deadline of the end of April. That target has been achieved – by more than 20,000.

Hancock is right to laud the impressive increase in the number of tests – a month ago the daily testing number stood at around 10,000. Targets are an effective of way of prioritising, and this target has certain focused the government’s – and the NHS’s – energies on ramping up testing capacity over the last month. NHS Providersm a membership body for NHS leaders, says that the target initially had a helpful and galvanising effect.

However, the true value of the target depends on how it fits into an overall strategy to ease the coronavirus lockdown and reduce cases of the disease.

The value of the target depends on the government’s strategy

Targets are most effective when they are aligned with purpose – governments need to measure what matters. The testing target, with a conveniently round 100,000 number and the end of April date, was not based on scientific advice from SAGE, as the chief medical officer acknowledged in his testimony to the Science and Technology select committee. Nor did the government say where it wanted to target these tests – be it in care homes, hospitals or the wider community.

The government’s options for easing the lockdown all require testing, so driving up the number will help - but the government’s target should depend on its overall exit strategy. If the government is going to move towards a ‘test and trace’ approach, then how many more tests will be needed and has the drive to reach 100,000 been made with the view to hit a number that fits a workable test-and-trace strategy? The government should be optimising the testing system for the long-term rather than racing to meet its own short-term deadline.

Sheer capacity is just one factor required to successfully implement a ‘test and trace’ strategy. It should not come at the expense of attention on other factors – such as whether the tests are easily accessible, how quickly the test results can be processed, and how they can form part of a tracing regime.

Focussing excessively on one target has distorted the government’s behaviour

The headlines that will follow today’s announcement should be swiftly disregarded. Rather than focussing on a single target, the government should be using a range of metrics. If the government wishes to partially lift the lockdown for specific industries, areas or age groups – an approach which seems sure to form part of the easing of restrictions – then it will need more data about testing numbers, capacity, accessibility and speed.

This is where the government should focus its efforts, but by placing pressure on itself and handing a stick to the media it has skewed its own priorities. Matt Hancock is reported to have sent an email to Conservative Party members with a link to book tests just days before the deadline[1] as part of a ‘get the vote out drive’. Even more worryingly, the government has reclassified what counts as a test – including those that have been sent to people’s homes, rather than those processed in laboratories. Of the 122,347 test carried out in the last 24 hours, 40,369 have just been sent out, rather than processed. Counting these towards the target suggests the government is more interested in testing for testing’s sake. NHS leaders have raised concerns that the 100,000 per day target is detracting from the priority of whether those who should be tested can actually get tested[2].

Urging the public to judge the government by this one simple target creates a game of high-stakes accountability – it was even suggested Matt Hancock could lose his job if he fell short. Rather than cheering how the government achieved this arbitrary target, Hancock’s attention – and the media’s – should be focused on the role that testing plays in taking the UK out of the lockdown. It may be mission accomplished on the politics, but the focus should be on the virus.

Additional research by Sukhvinder Sodhi

- Supporting document

- lifting-lockdown-how-approach-coronavirus-exit-strategy.pdf (PDF, 452.09 KB)

- Topic

- Coronavirus

- Keywords

- Health

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Publisher

- Institute for Government