Coronavirus illustrates the need to make the NHS more resilient

A decade of spending restraint means that an under-pressure NHS is not as resilient as it once was to deal with a major health crisis

The government’s response to coronavirus has been appropriate, but Graham Atkins warns that a decade of spending restraint mean that an under-pressure NHS is not as resilient as it once was to deal with a major health crisis.

As of 2 March, there have been 13,911 tests and 51 confirmed cases of Covid-19, a strain of coronavirus, in the UK. The World Health Organisation (WHO) consider the global risks posed by Covid-19 “very high” – but the risk of the UK being hit by an outbreak of infectious disease was not unexpected. The government’s risk register of civil emergencies – its assessment of the likelihood and severity of different kinds of civil emergencies – has listed pandemic influenza and emerging infectious diseases as two of the most likely risks over the next five years since 2017.

This assessment, and lessons learned from the 2009 swine flu pandemic, means the government has plans in place to respond to an outbreak of a virus like Covid-19. However, as the confirmed cases of Covid-19 continue to rise, a decade of reductions to resources have made it harder for the NHS to respond to an unexpected rapid increase in patients.

The NHS is less resilient now than it was in 2010

The NHS is still feeling the effects of austerity. Reductions in facilities – such as cutting bed numbers – may have increased NHS day-to-day efficiency, but they have also reduced its ability to respond to crises. The number of overnight acute hospital beds fell by 11% between the first quarter of 2010/11 and the first quarter of 2019/20, and the UK now has the second-lowest number of beds per capita of the G7 countries.

The NHS also faces staff shortages. The NHS currently has around 100,000 vacancies and has made increasing use of agency and ‘bank’ staff (NHS staff on short-term contracts). If dealing with Covid-19 requires substantially increasing staff numbers, the NHS may have to turn again to such staff, which could prove very costly, or look to bring former staff out of retirement.

The NHS will be able to increase capacity by reprioritising existing activity – such as cancelling some planned elective surgery – but these trade-offs will be difficult, particularly given the number of people waiting for elective surgery is already very long. As of March 2019, over four million patients were waiting for routine surgery such as hip or knee replacements.

Coronavirus has arrived when pressures are already high

Despite 2019/20 being the first year of the government’s new funding settlement for the NHS, performance has continued to decline. There is little slack to deal with a large number Covid-19 cases.

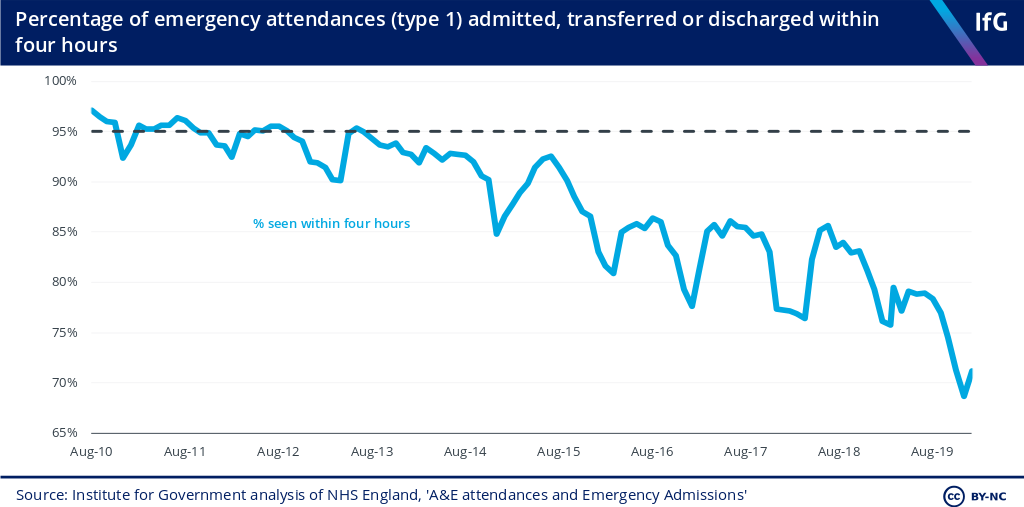

The percentage of patients attending A&E and seen within four hours in England continues to fall. In January 2020, only 71% of patients were admitted, transferred or discharged within four hours. Almost 340,000 patients waited longer than four hours in emergency departments in the same month and, concerningly, more than 100,000 patients experienced a ‘trolley wait’ – waiting from a decision to admit to actually being admitted into hospitals – longer than four hours.

Inevitably, the NHS has already found itself under increased pressure in the last few weeks. The higher volume of queries from patients has imposed higher workloads on NHS 111 call handlers and general practitioners to assess patients – Pulse, an online magazine for general practitioners, reports that the number of NHS 111 calls has “substantially increased” due to Covid-19 fears. And if the number of confirmed cases rise quickly, then the NHS will have to manage higher demand for beds and treatment in hospitals – when hospitals are already under pressure.

The government needs a plan for NHS resilience

The government’s current plan for responding to Covid-19 – to contain, delay, research and mitigate the virus – is sensible. Establishing regular Cobra meetings will help co-ordinate a cross-government response. It is also positive that the government has fast-tracked applications for capital funding required to build ‘pods’ – isolated areas in walk-in centres where patients who think they may have Covid-19 can be safely assessed – suggesting that it will make emergency cash available as and when it is required.

Covid-19 won’t be the last major new disease that the NHS faces. But regardless of unexpected outbreaks of new diseases, demand for healthcare is only set to rise in the future. To ensure the NHS has the capacity to respond to future shocks, the government should increase bed availability, either by investing in more beds or finding ways to safely reduce the amount of time patients need to spend in hospital beds. The response to Covid-19 will require short-term measures, but the government also needs to act in the long-term to be better prepared for any crisis that might strike in the future.

- Supporting document

- performance-tracker-2019.pdf (PDF, 4.23 MB)

- Topic

- Public services Coronavirus

- Keywords

- NHS Health Public spending

- Publisher

- Institute for Government