Boris Johnson should combine his reshuffle with his plans for Whitehall restructuring

Avoiding the temptation to tinker with his Cabinet will leave Boris Johnson with a more effective team of ministers.

With the prime minister reportedly planning to fill ministerial vacancies now ahead of a major Cabinet reshuffle in January, Tim Durrant argues that avoiding the temptation to tinker with his Cabinet will leave Boris Johnson with a more effective team of ministers.

A returning prime minister, fresh from triumph at the ballot box, must review his ministerial team to ensure he has the right people in place to deliver his priorities. But it makes sense for Boris Johnson to wait until the end of January for a big reshuffle, which can then happen at the same time as the changes in Whitehall departments he is thought to be planning once the UK has left the EU.

The prime minister needs to fill some ministerial vacancies immediately

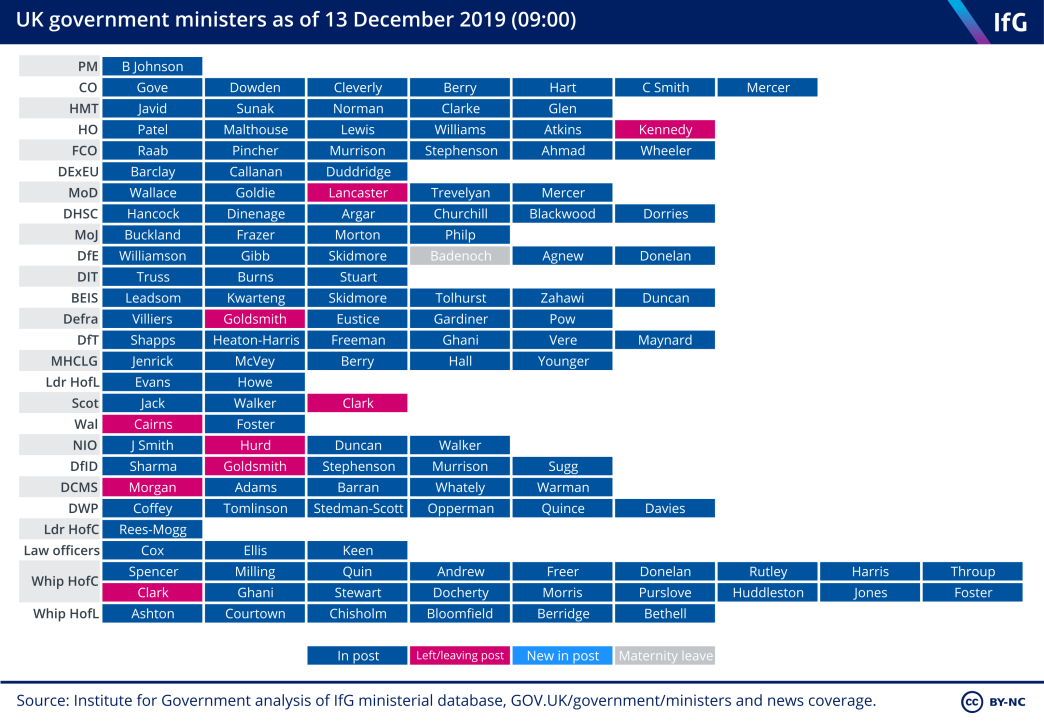

In the short term there are some gaps in the ministerial line-up that need to be filled, either because ministers did not stand in this election or because they lost their seats. At Cabinet level, the only gaps are Nicky Morgan, the former culture secretary, who did not run again; and Alun Cairns, ex-Wales secretary, who stepped down from the government before the election over claims he ‘knew about a former aide’s role in the “sabotage” of a rape trial’.

There are also gaps at lower rungs. Nick Hurd at the Northern Ireland Office, Seema Kennedy at the Home Office and Mark Lancaster at the Ministry of Defence all quit as MPs last week. Two former ministers lost their Commons seats last week: Colin Clark of the Scotland Office and Zac Goldsmith, who was a joint minister working across DfID and Defra and attended Cabinet. Goldsmith’s defeat made him the 24th minister who attends Cabinet to lose their seat since 1945.

A major reshuffle makes sense at the end of January

An effective majority of 87 will allow the prime minister to pass the legislation needed to deliver a smooth exit from the EU by 31 January 2020. But he will still need his team of DExEU ministers and civil servants in place to take the bill through Parliament.

That means the end of January would be a sensible moment to overhaul the ministerial ranks. The PM would have achieved one of his key campaign pledges and a reshuffle would signal his intention to move on to other priorities. It would be a chance to remove the Department for Exiting the EU from the map of Whitehall and make a series of other changes to government departments – all of which will have implications for the make-up of the Cabinet. Planned changes reportedly include merging the Foreign Office and Department for International Development; splitting the Home Office; merging International Trade and Business; and resurrecting the Department for Climate Change. With so many new or changed roles, there will be scope for a lot of ministerial moves.

Stability of ministerial tenure is a good thing

But once his January reshuffle is complete, Johnson should move people around as little as possible for the rest of his tenure. When he took over from Theresa May in July, Boris Johnson cleared out many of her ministers; he replaced over 50% of ministers at 20 out of 25 government departments. Many of his appointees joined the government, or the Cabinet, for the first time. This means they will still have been getting up to speed on what their role entailed when the election was called.

Former ministers all agree that spending at least two years in a job is necessary to be able to do it effectively. As Ken Clarke told our Ministers Reflect project, constant reshuffles mean that ‘you move on to the next department and you are back at the beginning…panicking again”. Frequent moves are a distraction from the business of running the country.

George Eustice, who resigned from Theresa May’s government but was reappointed by Johnson, said that continuity in ministerial roles is “very important”, at both secretary of state and junior ministerial levels. It allows ministers to build expertise in the policy areas they are responsible for, and it gives them the opportunity to build successful working relationships with each other, and with officials, in order to actually get things done while in office.

Now that Johnson has secured a large parliamentary majority, he can move from campaigning to governing. Building a top team for the long haul, rather than to get him through the next few months, would signal that he is serious about delivering on the promises he has made.

- Topic

- Ministers Civil service

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Department

- Department for Exiting the European Union

- Publisher

- Institute for Government