Civil Service Code

The Civil Service Code outlines the values and standards of behaviour that civil servants are expected to follow.

What is the Civil Service Code?

The Civil Service Code outlines the values and standards of behaviour that civil servants are expected to follow. It forms part of the terms and conditions of a civil servant’s contract. It is underpinned by the 2010 Constitutional Reform and Governance Act.

What does the Civil Service Code include?

The Civil Service Code defines and expands on four core values of the civil service:

-

‘Integrity’ means putting the obligations of public service above your own personal interests. This covers conflicts of interest, acting professionally and responsibly, handling official information sensitively and complying with the law.

- ‘Honesty’ means being truthful and open. This includes only using resources for authorised public purposes, and not misleading ministers, parliament or the public.

- ‘Objectivity’ means basing your advice and decisions on rigorous analysis of the evidence. This includes not obstructing the implementation of policies once decisions are made.

- ‘Impartiality’ means acting solely according to the merits of the case and serving equally well governments of different political persuasions. This includes both general impartiality (treating all parties fairly and equally) and political impartiality (retaining the confidence of ministers, while ensuring you could establish the same relationship with a future government).

The code is meant to guide civil servants’ behaviour and is not a comprehensive manual that tells civil servants what to do in various situations. The code explicitly does not cover human resources and management issues.

The Civil Service Code sits alongside of the civil service management code. This document goes into more detail about performance and conduct alongside other issues of employment like development, pay and leaving the civil service. Departments also issue guidance on specific issues of conduct like how civil servants should use social media.

Who is subject to the Civil Service Code?

The code covers all existing civil servants, whether employed on a permanent basis or not. This does not include agency workers, consultants or contractors. The Civil Service Code does not cover people employed in the wider public sector, for example parliamentary staff, NHS workers, some arms-length bodies like the Environment Agency or local authorities. They are subject to their own organisational rules and codes of conduct.

The Constitutional Reform and Governance Act (CRAG) also created a similar code for the diplomatic service (as opposed to the home civil service), and civil servants who serve the Scottish and Welsh governments. The CRAG does not cover the Northern Ireland executive, but Northern Irish civil servants are subject to a similar code called the Code of Ethics.

As temporary civil servants, special advisers also have a code of conduct. They are also required to follow the Civil Service Code, but as political appointees they are exempt from the values of impartiality and objectivity.

There is some contention over the status of personal ministerial appointments, often known as government ‘tsars’, who are neither civil servants, special advisers, or ministers. The Civil Service Code does not account for such roles, where they are not employed as civil servants, and so their political impartiality, relationship to the civil service, and how they are held to account is unclear under the Civil Service Code.

How is the code enforced and what is the role of the Civil Service Commission?

Possible breaches of the Civil Service Code are normally first dealt with internally by departments. Where civil servants have concerns that they have been asked to breach the code, or that another civil servant has, they can report this to their line manager, someone in their line management system, or a nominated officer in their department.

If a civil servant is dissatisfied with the department’s response, they can raise an appeal to the Civil Service Commission, an independent body whose longstanding existence was formally established by statute as part of the CRAG.

One of the Civil Service Commission’s main functions is to investigate complaints under the Civil Service Code brought to it by any current civil servant once that complaint has been investigated in the relevant department. The commission is the final arbiter on whether there has been a breach of the code. However, it has no formal sanctioning powers: it cannot dismiss civil servants or apply financial sanctions. Instead the Commission publishes details of its investigations and findings and makes recommendations to the department as to how breaches can be avoided in the future.

If a civil servant has gone through these processes and has been told that they and their department have acted properly then they have not breached the code. But if the civil servant still cannot reconcile the actions they are being asked to take with their understanding of the Civil Service Code, then they have little choice but to resign.

This is more likely to be an issue when there is an allegation that a minister has asked a civil servant to breach the code, rather than when a civil servant has breached the code independently. This is because the civil service is ultimately managed by ministers, and if a civil servant considers those same ministers to be asking them to breach the Civil Service Code, their position could become untenable.

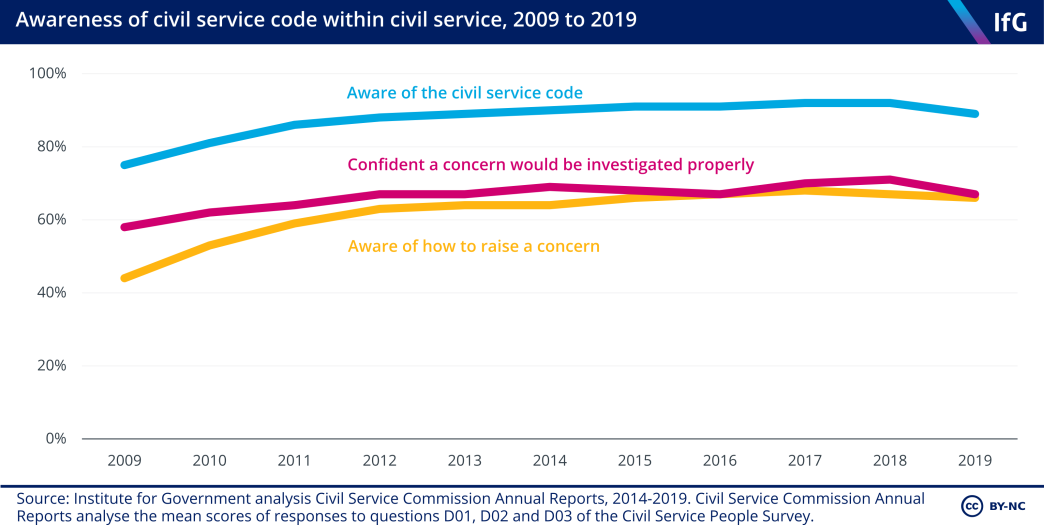

The Civil Service Commission is also responsible for promoting the Civil Service Code. It monitors staff knowledge about the code and confidence in departmental handling of a code complaint through three questions in the annual Civil Service People Survey.

What is the constitutional status of the code?

In setting out the core values of the civil service, the Civil Service Code promotes the integrity and impartiality of the civil service.

The 2010 Constitutional Reform and Governance Act set out the requirement for a Civil Service Code in statute and established the Civil Service Commission’s role. The Act states that ‘the code must require civil servants … to carry out their duties for the assistance of the administration … whatever its political complexion’ and must require the civil servants to carry out their duties with ‘integrity and honesty’ and ‘objectivity and impartiality’. These minimum requirements can only be changed by an act of parliament.

The government can add additional requirements or change the contents of the code in other ways. Such changes to the Civil Service Code must be laid before parliament, but do not need to be voted on. For example, in 2015 the government added an additional point to the ‘integrity’ section to require civil servants to receive ministerial authorisation before speaking to the media.

The code has not always had statutory status. A civil service code was first published in 1996 on the recommendation of the Treasury and Civil Service Committee, the FDA (a trade union for senior civil servants) and the Nolan Committee on Standards in Public Life. It reflected the conventions of the role of the civil service, and its wording was based on previous memos on the duties and responsibilities of civil servants.

The Ministerial Code – the code of conduct issued by the prime minister to ministers – references the Civil Service Code, saying that ministers must not ask civil servants to breach the code. However, the ministerial code is not statutory, and is enforced at the discretion of the prime minister.

What are the limits of the Civil Service Code?

While the Civil Service Code promotes the integrity and impartiality of the civil service, ultimately the management of the civil service, and therefore of its integrity, rests with the prime minister. The same legislation which put the Civil Service Code in statute also established that the minister for the civil service (who is by convention the prime minister) had the power to manage the civil service.

This means that the protection offered by the Civil Service Code has limits, especially if it is a minister who has allegedly asked civil servants to breach the code and the minister has the confidence of the prime minister. For example, former cabinet secretary Sir Mark Sedwill had to explicitly tell civil servants that working on the UK Internal Market Bill was not a breach of the Civil Service Code in September 2020, despite the possibility of it breaking international law (and therefore breaching the code) as ministers – via the Law Officers – deemed it legal.

The statute around the Civil Service Code does not therefore establish the civil service as an independent entity from the government, and even the Civil Service Commission only has the power to recommend improvements where departments have breached the code, rather than give sanctions.

- Topic

- Civil service

- Department

- Cabinet Office

- Publisher

- Institute for Government