How is election spending regulated in the UK?

The next election is likely to see record levels of spending by parties and their candidates.

Party campaign spending is regulated by the Electoral Commission, an independent body overseen by the Speaker of the House of Commons, while returning officers (local council officials) oversee spending by candidates in each constituency.

What spending is regulated at general elections?

Regulated spending includes a wide variety of costs, from party political broadcasts to leaflets.

Some notable expenses are excluded, however. Parties must count the cost of rallies, but do not need to include the cost of annual conferences. 45 Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000, sch. 8, s 1 (8) Candidates and non-party campaigns have to include money spent on staff in their returns, but political parties do not. 46 For more information on the details of regulated spending and the vexed question of party staff costs see J. Fisher, The regulation of political finance: Choppier waters ahead?, Institute for Government, 28 April 2023

How much can political parties spend at general elections?

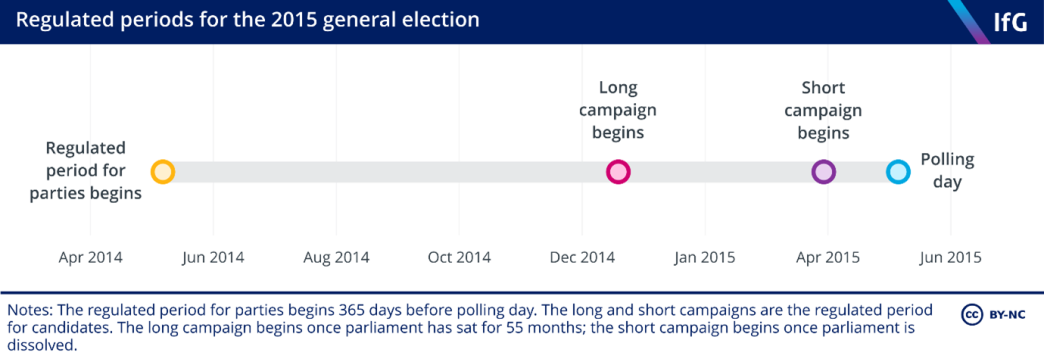

Limits only apply to party spending during the 365 days before polling day – known as the ‘regulated period’. 47 Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000, sch. 9, s 3 (7) Each party can spend £54,010 for each constituency that they contest. A party that chooses to contest all 632 seats in Great Britain at the next election will therefore be able to spend just over £34m.

The limits were increased in November 2023, rising 80% to account for inflation since they were instituted in 2000. Since 2010, the government has had a statutory duty to either raise the limits in line with inflation once a parliament has lasted two years or to make a statement explaining why it is not doing so. 48 Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000, s 155 (4). The deputy prime minister made such a statement ahead of the 2015 election (HCWS489). The government failed to comply with their statutory duty before the 2019 election At previous elections, contested under the old limits, a party standing in all seats in Great Britain would only have been able to spend just under £19m.

For parties that contest only a small number of constituencies, there is some flexibility. For instance, every party is allowed to spend just over £1.4m in England, regardless of the number of seats they contest. This allowed the Women’s Equality Party to spend just over £100,000 at the 2019 general election, despite standing only three candidates (the per constituency limit was then £30,000 per seat contested). Similar flexibility is applied to the limits in Scotland and Wales, but not Northern Ireland.

Notably, spending restrictions apply retrospectively, even in the case of a snap general election. This means that the regulated period usually begins before the date of the next general election is known. At the last general election, the regulated period began on 12 December 2018. The regulated period for the next general election will have already begun.

How much can candidates spend while parliament is still sitting?

Individual candidates also spend money at elections. There are two periods of restrictions for candidate spending, known as the ‘long campaign’ and the ‘short campaign’. Money spent by candidates during these two periods is in addition to party spending and does not count towards party spending limits.

The long campaign refers to the final few months of a full-length parliament: it begins once parliament has sat for 55 months. 58 Representation of the People Act 1983, s 76ZA (1) Sometimes there is no long campaign because a general election has been called before this 55-month point – this was the case in both 2017 and 2019. The long campaign for the next election will begin on 18 July 2024, if parliament has not already been dissolved.

A limit on candidate spending is introduced at the beginning of the long campaign and increases proportionately for each additional month that parliament sits. This limit is calculated as a proportion of what the maximum limit could be, if parliament sat for a full 60 months. 59 These proportions rise from 60% for parliaments dissolved in the 56th month to 100% for those dissolved in the 60th month, increasing in 10% intervals for each month. This maximum limit is a fixed sum of £40,220 plus an allowance per registered voter. The allowance is 8 pence in a borough (urban) seat and 12 pence in a county (rural) seat. 60 Representation of the People Act 1983, s 76ZA (2)

This means that if the current parliament lasts a full five years – until 17 December 2024 – candidates could have spent around £46,000 (in an average borough seat) and £49,000 (in an average county seat) before parliament is dissolved.

Candidate spending that occurs in the regulated period for parties but before the beginning of the long campaign (or before dissolution when there is no long campaign) is counted towards party spending limits instead. 61 All relevant spending is party spending unless it falls to be included in a candidate return: Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000, s 72 (7) (a); see ‘R v Mackinlay and others’ [2018] UKSC 42, p. 5

How much can candidates spend once the election is called?

The short campaign begins from the day after parliament is dissolved. At this point, a new set of spending limits apply to those who have already announced their candidacy. The short campaign will not begin for undeclared candidates until they have been nominated by their party or announced their intention to stand. 62 Representation of the People Act 1983, s 118A

During the short campaign, candidate spending limits are calculated by taking the fixed sum of £11,390 and adding the same allowance per registered voter as is applied in the long campaign. 63 Representation of the People Act 1983, s 76 (2) As such, candidates can spend up to £17,000 in an average borough seat or £20,500 in an average county seat. This is in addition to any money spent during the long campaign (which ends when parliament is dissolved).

These limits are much higher for by-elections, where a fixed cap of £180,050 applies to candidate spending. 64 Representation of the People Act 1983, s 76 (2) (aa)

Like the limits for parties, candidate spending limits were increased in November 2023 (for both the long and short campaigns) – rising 30% to account for inflation since they were last set in 2014.

How much might parties and their candidates spend at the next general election?

The spending limit at the next election will vary depending on the number of candidates and the timing of polling day.

In the event of a November election, 65 This worked example assumes an election held on 14 November 2024. In this case, parliament would be dissolved on 10th October, in its 58th month. Candidate spending limits are calculated for each constituency using data from the House of Commons Library. a party standing in all 632 seats in Great Britain would be able to spend just over £70m during the regulated period. This limit would consist of £34m of party spending, and an average of just over £57,000 per candidate (£38,000 during the long campaign and £19,000 during the short campaign). In this scenario, the regulated period for parties would begin in November 2023 and any spending before this would be unregulated.

Who else spends money at elections and what limits apply to them?

A small proportion of spending at elections is conducted by third parties – groups like charities and trade unions that do not stand candidates of their own, but campaign for particular outcomes. These non-party campaigns account for a growing proportion of election spending: 8.5% in 2019, up from just 3.3% in 2015. 66 Institute for Government analysis of Electoral Commission data Like parties, spending limits apply to these groups in the 365 days before an election.

Non-party campaigns must notify the Electoral Commission if they intend to spend more than £10,000 across the UK. They must register with the Commission and submit spending returns if they spend more than £20,000 in England or more than £10,000 in the devolved nations. 68 Electoral Commission, Non-party campaigner Code of Practice Foreign entities cannot spend more than £700 (except groups of UK overseas electors).

Several spending limits are then applied to registered campaigns. These include limits on total spend in each nation, a limit on spending in each constituency (with certain national spending also allocated on a constituency level) and a limit on ‘targeted spending’ in support of a particular party or its candidates.

Separate limits apply to local non-party campaigns, conducted in a single constituency only, which are governed under separate legislation and are not the responsibility of the Commission.

The Committee on Standards in Public Life has described these rules as particularly ‘complex and difficult to understand.' 75 Committee on Standards in Public Life, Regulating Election Finance, July 2021, 8.16 An independent review in 2016 recommended some 30 changes, but the government chose not to implement these in the Election Act 2022. 76 Lord Hodgson of Astley Abbot, Third Party Election Campaigning – Getting the Balance Right, 2016

Spending by third parties only counts towards these limits if it meets a purpose test: it must be reasonably regarded as intended to promote the election of particular parties, or supporters of particular policies (whether parties or candidates), or particular categories of candidates. This can include negative campaigns against opponents of these groups. The Electoral Commission has detailed several factors to be considered as part of this test in its Code of Practice for non-party campaigns.

How are spending limits enforced?

Political parties and registered non-party campaigns submit spending returns to the Electoral Commission. Parties have three months to submit these, or six months if they have spent more than £250,000. The Committee on Standards in Public Life has recommended that this latter limit be reduced to four months. 77 Committee on Standards in Public Life, Regulating Election Finance, July 2021, 7.14

The Commission investigates cases where they have a reasonable grounds to suspect an offence and can impose fines of up to £20,000. The Commission itself has said that this maximum fine is ‘not proportionate for the most serious instances’ and requested it be raised. 78 Electoral Commission, Committee on Standards in Public Life: Review of electoral regulation: Written evidence – submission 16, 24 July 2020, 20 It can refer more serious matters to the police for prosecution, although no prosecution has ever been brought forward. 79 Commons Library, Elections Bill 2021–22, 1 September 2021, p. 74.

While the Commission now collates and publishes information from candidate spending returns, the regulation of candidate spending is a matter for returning officers and the police. The Electoral Commission has recommended that they should be given new powers to regulate candidate spending under a civil enforcement scheme. 80 Electoral Commission, Committee on Standards in Public Life: Review of electoral regulation: Written evidence – submission 16, 24 July 2020, 31–35

- Topic

- Ministers Regulation

- Publisher

- Institute for Government