HS2 is still the quickest way to invest in northern and Midlands transport

HS2 is still the quickest way for Boris Johnson to fulfil his plans to upgrade northern and Midlands transport.

Spiralling costs mean HS2 barely gives value for money, but Graham Atkins says it is still the quickest way for Boris Johnson to fulfil his plans to upgrade northern and Midlands transport

HS2 has been beset by spiralling costs since it was first proposed in 2010. Its estimated budget has more than doubled in real terms over the last decade. A leak of the independent review of HS2 suggests the final bill for the line could rise to £106bn. That means the project is now on the cusp of not providing value for public money, even according to government models, and there will be pressure on Boris Johnson from Conservative MPs to make HS2 the most high-profile of his slaughtered sacred cows.

Any further increases in costs would tip HS2 toward being a project that is not value for money, judged on the government’s own cost benefit analysis. And even if the bill weren’t to rise, other projects could be better value for money.

But if the prime minister wants to fulfil quickly his promise to “level up” the country and invest in northern and Midlands transport projects, then continuing with HS2 is his only viable option.

As the cost of HS2 rises its value has fallen

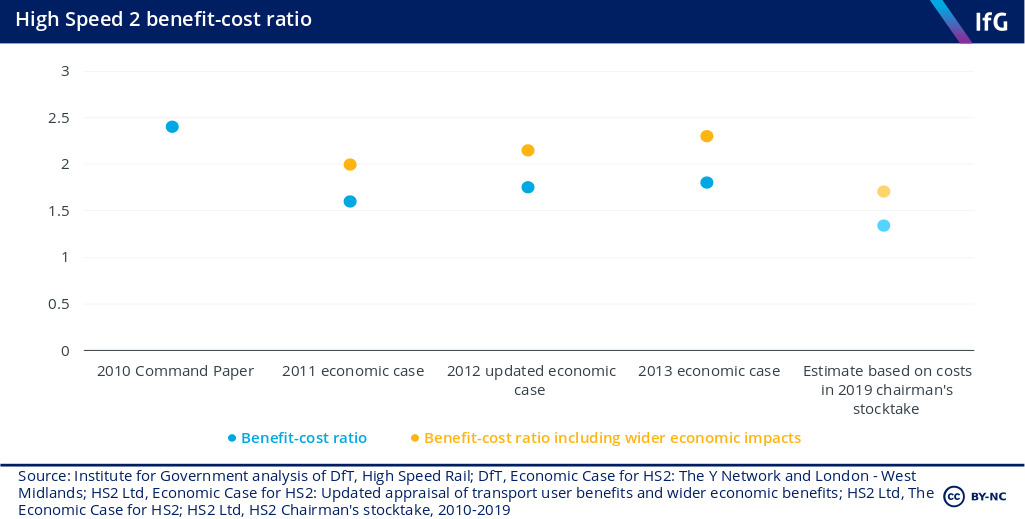

HS2’s opponents have plenty of ammunition, with a fall in the government’s projections of HS2’s benefit-cost ratio – the value of the economic, social, and environmental benefits delivered for each pound of public money invested.

Initially estimated as delivering £2.40 of benefit for each pound of public money spent, the costs of HS2 have risen since the government’s last full economic assessment of the scheme in 2013. The chair of HS2 Ltd, Allan Cook, published a stocktake last year which estimated that HS2 will now cost between £72.1bn and £78.4bn, an increase of between 29% and 41% on the £55.7bn agreed in the 2015 spending review. Assuming HS2’s benefits remain unchanged, our analysis makes HS2’s benefit-cost ratio now only 1.3 – which means HS2 is now ranked as a low value-for-money project.

The leaked Oakervee review suggests that costs could rise by as much as 20% above this again, which risks the costs of the project exceeding the benefits.

It is hard to calculate the exact value-for-money for a project the size of HS2

However, when wider economic impacts are included, such as the benefits associated with bringing people and businesses closer together, the government’s analysis suggests that HS2 is still medium value-for-money.

The actual benefits of HS2 may be higher than current models show, if some “dynamic effects” – benefits that emerge because of changes only once it has started operating – are included. Those might include productivity gains from people and companies relocating in response to better transport. The government itself has previously admitted that its cost-benefit analysis “was not developed [for schemes] on the scale of HS2”. Previous Institute for Government research found that another major rail project, the Jubilee Line Extension, was approved with a benefit-cost ratio of 0.95 but was later evaluated to have been worth 1.75.

Alternative, better value transport projects will be hard to deliver quickly

If the government’s main objective is to give the north of England better transport, there are other potential projects that have higher benefit-cost ratios than HS2. ‘Northern Powerhouse rail’, a proposal for a new rail line between cities in the north west and the north east, would have a higher benefit-cost ratio than HS2 according to Oxera, an economic consultancy. Smaller transport upgrade projects – such as road bypasses or tram extensions – typically have higher benefit-cost ratios too, and could generate higher returns than HS2.

But there are unlikely to be enough “shovel-ready” projects able to absorb the money which would have been spent on HS2. New transport projects require detailed designs, business cases, planning permission, and procurement before they can start construction – all of which take years. This constraint should not be underestimated. Governments of all stripes have consistently been over-optimistic in how quickly and how cheaply they will be able to deliver infrastructure projects. A shift from HS2 to alternative projects will inevitably delay the process of starting to build new infrastructure in the North and Midlands.

The government needs to grip costs and integrate HS2 with other plans

If spending more on the north and the Midlands immediately is the priority, then the government should proceed with HS2 – but it must change its approach to completing the project.

HS2 is now on the cusp of value for money. Following the Oakervee independent review the government must reset HS2’s budget and develop a full, final budget – once and for all – that captures total costs or as close to those as possible, including a sum for contingencies. Previous Institute for Government research found that once the government set a realistic budget with enough contingencies for the Olympic Games in 2007, “it was stuck to and gave everyone a basis for proper management” (after a period of dramatic cost overruns).

Once this is in place, the government must maximise the potential benefits of HS2 by integrating its plans with councils’ plans for housing and local economic development. The government’s National Infrastructure Strategy, due to be published in March, should make clear how it will do this.

Arguments to cancel HS2 may grow louder and if costs rise further they will gain force. For now, the case for this disputed, poorly managed and elastically budgeted megaproject being the quickest way to invest in northern and Midlands transport projects remains just about intact.

- Supporting document

- IfG_infrastructure_strategy_final.pdf (PDF, 763.73 KB)

- Topic

- Policy making Public finances

- Keywords

- Infrastructure High Speed 2 Transport

- Publisher

- Institute for Government