‘Health week’ can’t hide slow progress on Rishi Sunak’s NHS pledge

While some waiting time data is moving in the right direction, the prime minister is still some way off meeting his NHS pledge.

The biggest story of the government’s ‘health week’ should be the ongoing failure of ministers and doctors to find a solution to the ongoing pay dispute, writes Stuart Hoddinott

The government’s ‘health week’ is the latest summer attempt by No10 to get on the front foot. Ministers are keen to talk up policy initiatives, but this is also an opportunity to evaluate the government’s progress against Rishi Sunak’s promise to “cut NHS waiting lists”. 6 https://www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-outlines-his-five-key-priorities-for-2023 With a general election approaching, there has been little improvement in many of the major indicators across the service and the biggest drag on performance – ongoing industrial action – remains an unresolved problem.

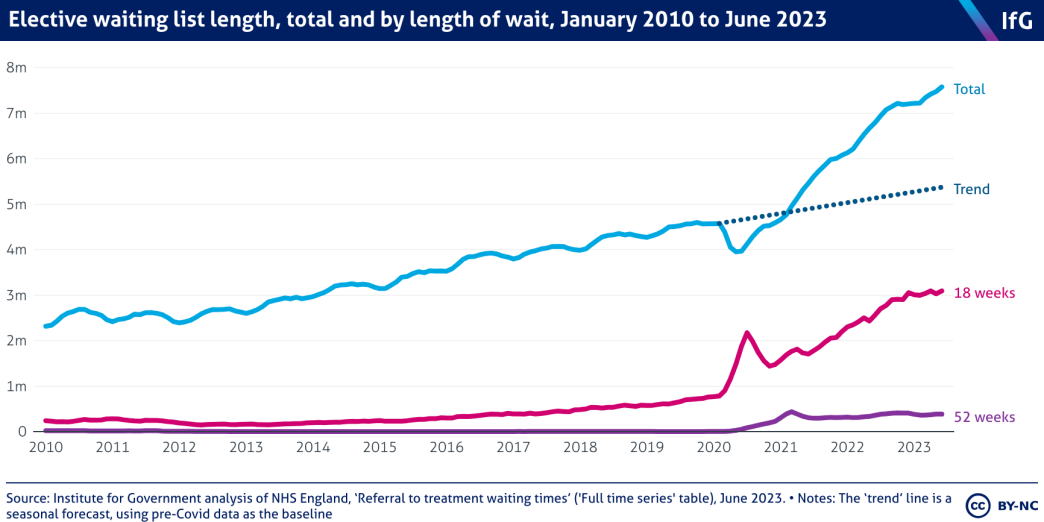

The waiting list sits at record levels, though there are fewer long waiters

Elective data released last week shows that the waiting list reached another record high in June of 7.57 million, roughly 362,000 more than when Sunak made his pledge in January.

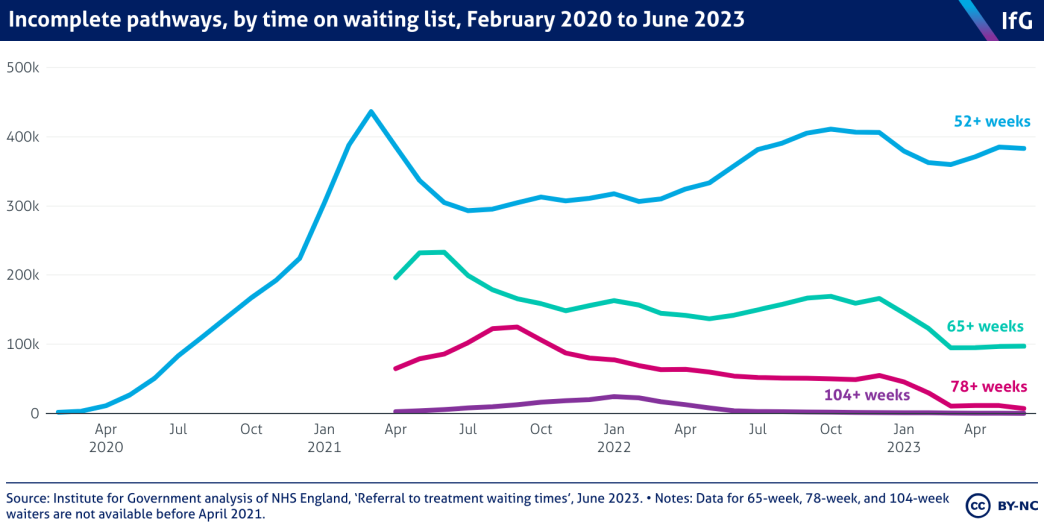

June data showed that fewer people are now waiting for more than 65, 78, and 104 weeks than in January 2023, but there are more waits of longer than 52 weeks: 383,000 in June compared to 379,000 in January.

The NHS also missed the most recent of its elective targets: to clear the number of waits that were longer than 78 weeks by the end of April 2023. At the end of June, the number of 78 week waiters was still 7,177.

The service’s next target is to eliminate 65 week waits by the end of March 2023. While there was a substantial reduction in that group at the beginning of the year, progress has stalled. Each successive target becomes harder to hit as the shorter timeframe makes it more difficult to plan how hospitals will clear long waiters from the list.

There has been a reduction in the median waiting time for elective care between January and June – from 14.6 to 14.3 weeks. But a 14.3 week wait is still the fourth highest month on record, behind only December 2022, January 2023, and February 2023, months when the NHS was experiencing its worst ever winter crisis. In contrast, the median wait for treatment in June 2019 (the last comparable pre-pandemic month) was 7.5 weeks.

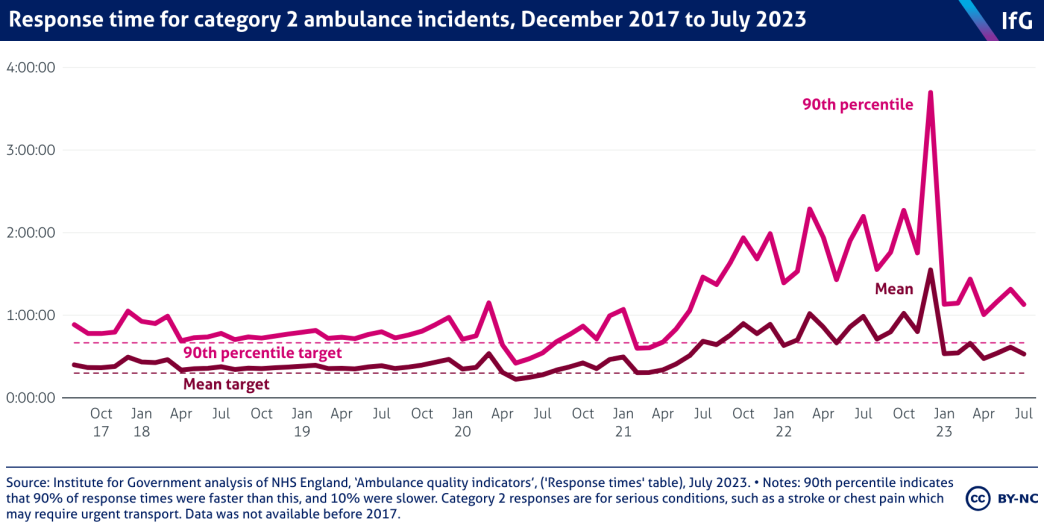

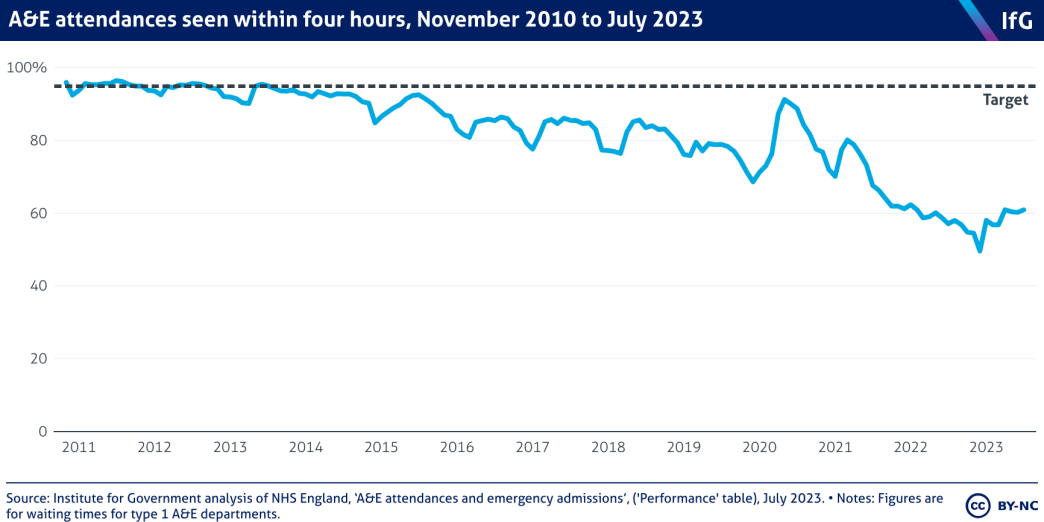

An end to winter has seen emergency waiting times improve

On some key metrics for urgent and emergency care (UEC), there has been a large improvement in performance. Category 2 ambulance response times – which includes calls for serious conditions such as strokes or chest pain – have dropped from a record high of 1 hour 32 minutes mean response time in December 2022, to 31 minutes 50 seconds in July 2023. Though this is still 76.9% higher than the 18 minute target.

Similarly, there has been an improvement in A&E waiting times, with 60.9% of people waiting less than four hours in type-1 A&Es in July 2023, up from 49.6% in January 2023. Once again, however, this is still well below the previous target of 95% and even below the NHS’s revised target of 76% for 2023/24. 8 https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/PRN00021-23-24-priorities-and-operational-planning-guidance-v1.1.pdf , p.7

It is difficult to disentangle whether government intervention or a post-winter improvement in performance is responsible for improving UEC waiting times, but falling ambulance response times and A&E waits suggest more funding for improving delayed discharge and expanded use of virtual wards could be having an impact. It is also possible to argue that the context of the winter of 2022/23 was uniquely bad, with a record flu season and ongoing high levels of Covid occupancy in hospitals, meaning that Sunak effectively picked the lowest possible starting point for future comparison. The real test for the resilience of UEC services and the effectiveness of the government’s policies will be this coming winter.

A resolution to industrial action would boost NHS performance

The single biggest drag on NHS performance at the moment is ongoing industrial action. Strikes have led to more than 750,000 inpatient and outpatient appointments being delayed and have had an unquantifiable impact on other areas of the health system.

The impact of industrial action is not limited to strike days themselves, with planning for strikes consuming precious managerial and clinical time that would otherwise be spent on preparing for winter or better planning elective care to bring down the waiting list. Speaking to the IfG, some NHS staff compared the impact of the strikes to Covid, inflation, and last winter’s flu season. But those crises were beyond the control of the government or those working in the health service. Sunak and Barclay could resolve ongoing doctors’ industrial disputes. Equally, doctors have a responsibility to make credible demands. The failure of both sides to reach agreement should be the biggest story of the government’s ‘health week’ as it continues to hinder Rishi Sunak’s chances of hitting his NHS pledge.

- Topic

- Public services

- Keywords

- NHS Public sector

- Political party

- Conservative

- Department

- Department of Health and Social Care HM Treasury

- Public figures

- Rishi Sunak Steve Barclay

- Tracker

- Performance Tracker

- Publisher

- Institute for Government