10 claims from the EU referendum campaign

During the referendum campaign, many people predicted what Brexit would look like – and many made claims about what the future would hold.

The economy did not go into recession, despite the then-chancellor's gloomy predictions.

The UK and EU were able to conclude the Brexit process within four and half years.

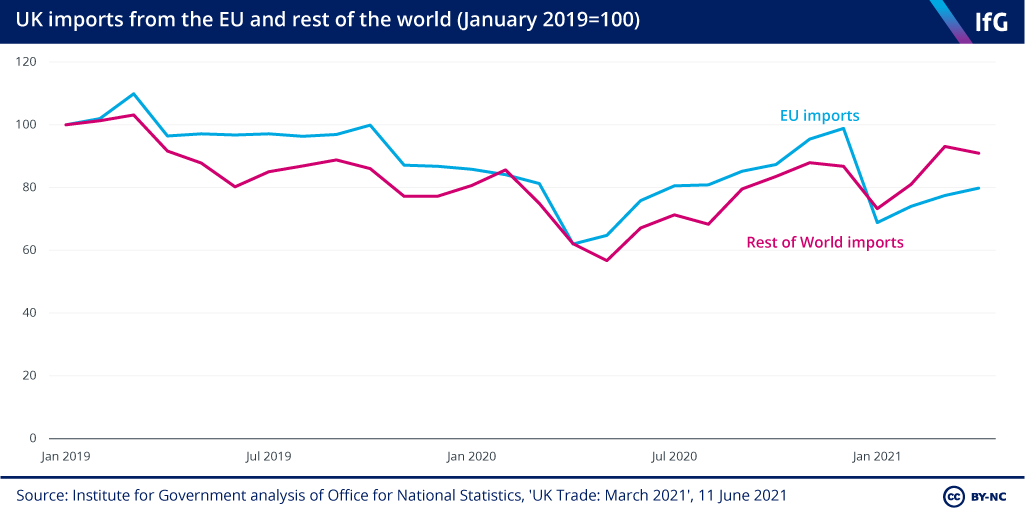

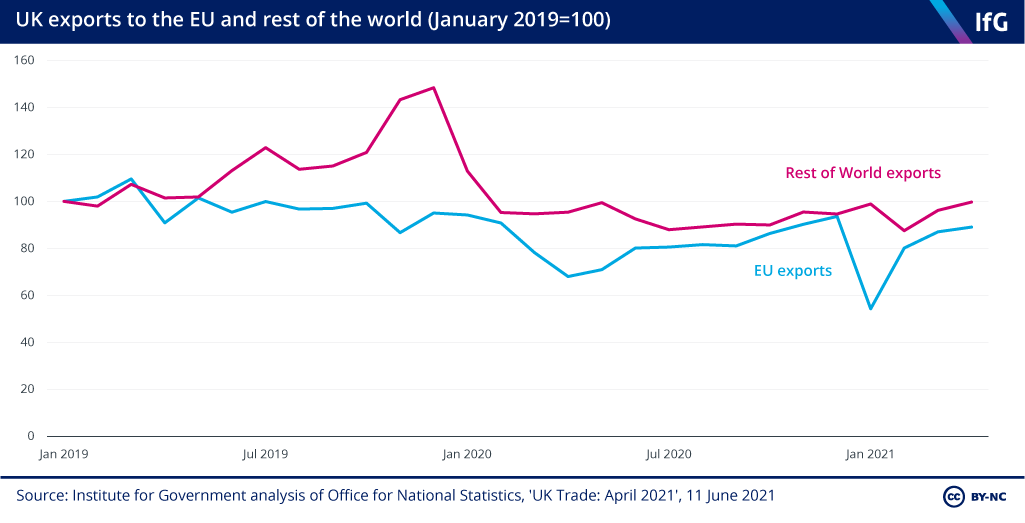

The UK’s trading relationship with the EU fundamentally changed at the end of the Brexit transition period, with the UK leaving both the EU single market and customs union.

Fisheries was a hotly contested topic during the 2016 referendum campaign.

When the UK was a member state, it had access to a suite of measures which facilitated cooperation on policing and criminal justice.

The issue of the Irish border has been problematic throughout the Brexit process.

king back control of UK laws and removing the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice, was a red line during the Brexit negotiations.

The UK government is now able to control EU immigration in a way that has not been possible for decades.

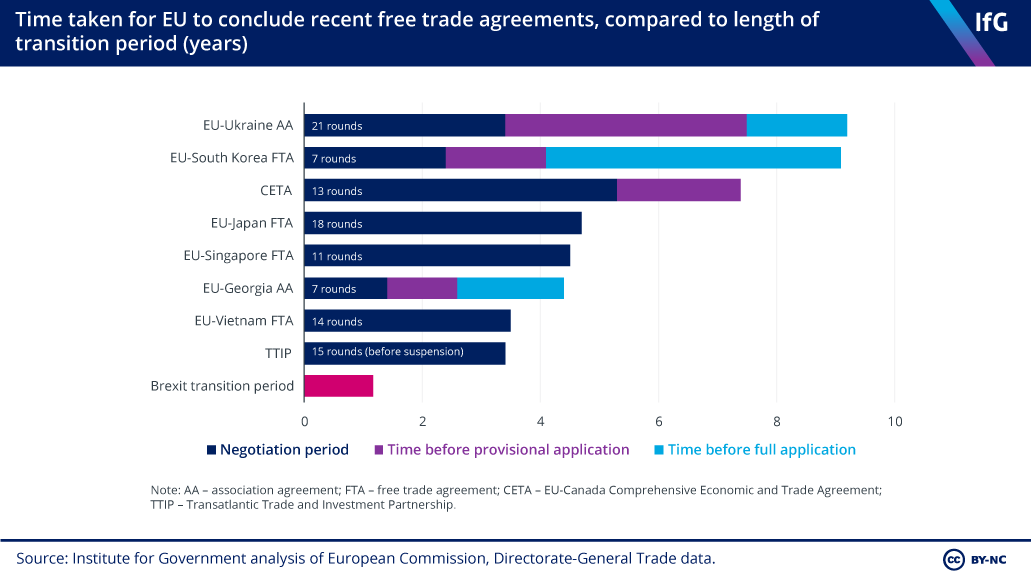

The freedom to negotiate and sign its own free trade agreements (FTAs) was one of the central goals of the government throughout the negotiation period.

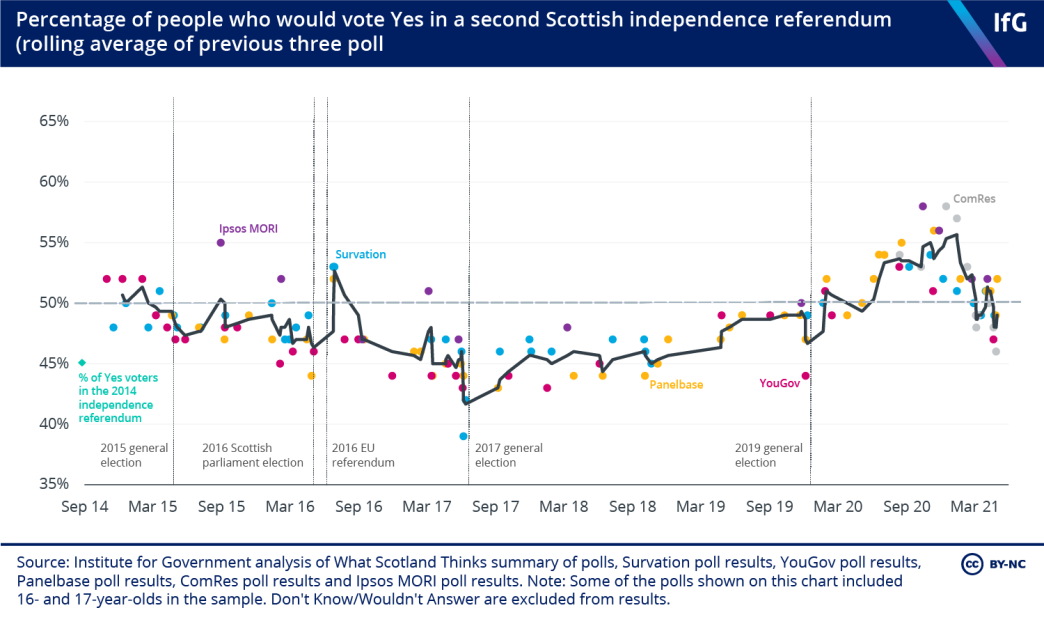

While the UK-wide 52% Leave vote gave the government a mandate for Brexit, a majority of people in Scotland (62%) and Northern Ireland (56%) voted Remain.