Collapsing civil service pay undermines the government’s ability to deliver

Why the civil service strike demonstrates the risks of the government’s attempt to hold down pay.

Using findings from the recently launched Whitehall Monitor 2023, Rhys Clyne explains why the civil service strike demonstrates the risks of the government’s attempt to hold down pay

High levels of inflation meant that civil service pay fell starkly in 2022, as it did across the public sector. In other circumstances, this drop might be met by a higher pay award this year to plug officials’ lost spending power. But amid the worsening fiscal outlook, the government is trying to hold down civil service pay even more tightly than in the rest of the public sector, endangering the government’s deliver capability.

The Conservative-Liberal Democrat Coalition used pay restraint in a similar way during the austerity programme. A two-year pay freeze between 2011 and 2013 was followed by a 1% average pay cap between 2013 and 2017, saving an estimated £10-20bn in 2021/22 prices.

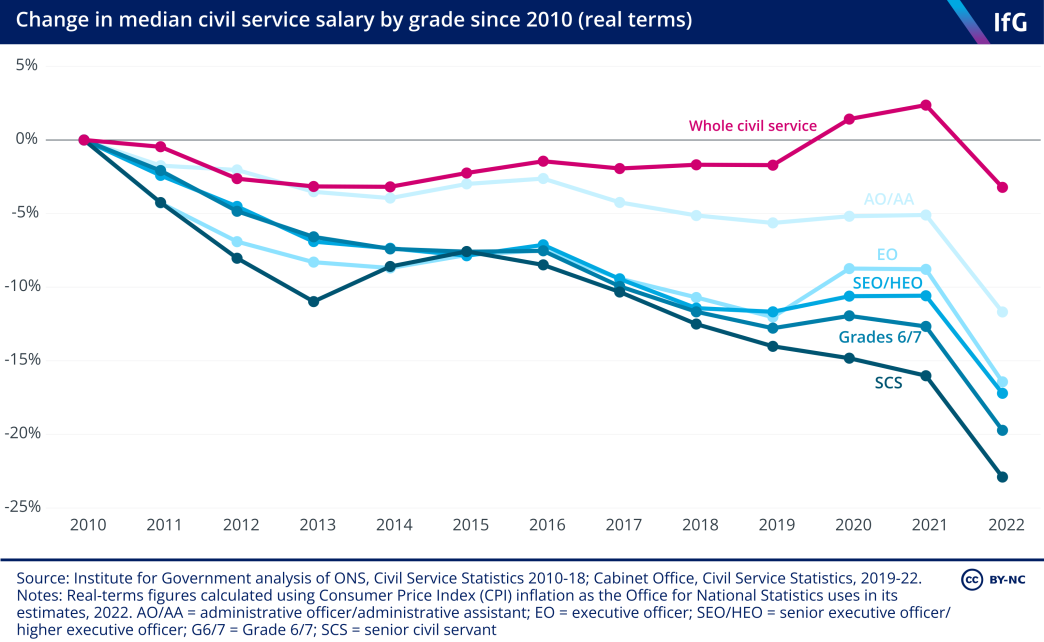

But pay restraint in the early 2010s followed a period of pay growth, whereas last year’s drop in wages came after a sustained period of real-terms cuts. Since 2010 civil service salaries have reduced in real terms by between 12% at the most junior grades and 23% at the most senior (though an increasingly senior workforce means overall median pay has fallen less markedly). The cumulative effect of these real-terms cuts was compounded by inflation last year to create a worrying set of circumstances for those responsible for managing the civil service workforce. These are particularly difficult conditions to impose pay restraint.

The 2% award on the table is small compared to the wider public and private sectors

The civil service is unusual in how its pay is set. The review body on senior salaries (SSRB) sets pay for the senior civil service in a similar way to most other parts of the public sector. But there is no pay review body for the rest of the civil service. Instead, Treasury and Cabinet Office officials advise ministers, who set pay remit guidance each year for departments to follow. Without an independent body, this process lacks the outside expert input available to other parts of the public sector.

This process often results in Treasury ministers deciding on relatively low pay awards for junior and mid-ranking civil servants compared to other, comparable professions. That acts as a downward ratchet on senior officials’ pay, as even when the pay review body proposes higher awards for them, it is rightly seen as unsustainable to give higher increases to the top of the office than officials at lower grades.

And this is what has played out this year. Both junior and senior civil servants have been offered a pay increase of 2%, with departments having flexibility to pay up to 3% in certain circumstances. This guidance was published in March 2022, before inflation climbed to 11% in October. Departments are unable to rebalance remuneration packages away from the relatively generous pensions and towards take home pay, as would help for some. And the overall increase is much lower than comparable professions. In the case of ongoing industrial action across the wider public sector, agreements of 4-5% awards have been made where they have been reached, while the private sector has agreed awards over 6%.

Low pay will undermine recruitment, retention and ultimately effectiveness

Ministers are prioritising holding down pay because they see it as an important part of restraining public spending and – they argue, unconvincingly – to avoid fuelling inflation. But the civil service pay bill amounts to approximately 1% of all government spending, and pay restraint is not cost-free.

Morale in the workforce has been getting worse for the past two years. Dissatisfaction with pay is a significant contributing factor. Reports in the Times suggest just over a quarter (28%) of officials felt their pay “adequately reflects” their performance in 2022, down from 38% in 2021. This is a problem because, simply put, low morale makes the civil service less effective at delivering ministers’ priorities.

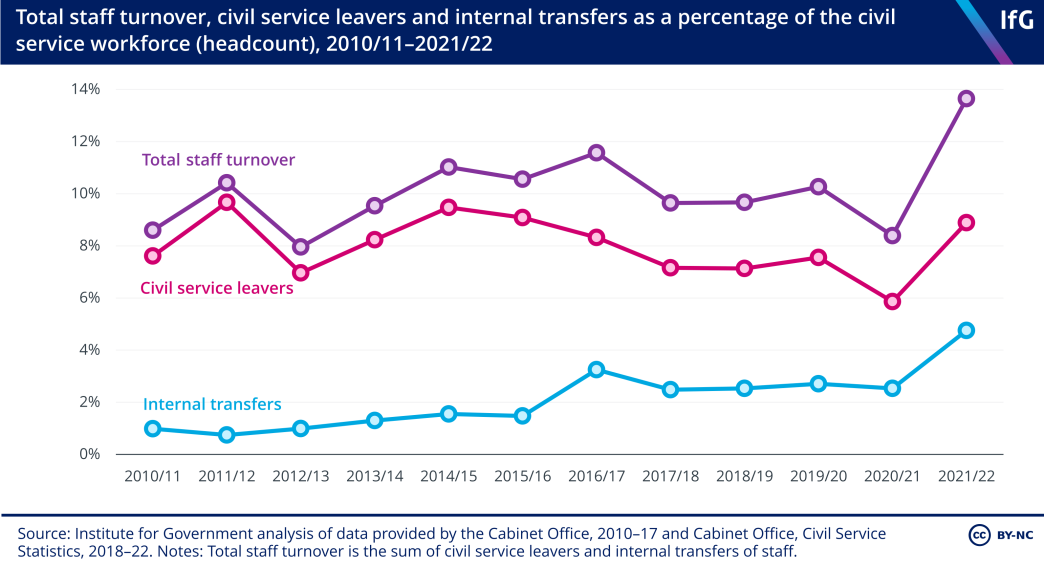

Low pay also contributes to staff turnover. 14% of officials either moved departments or left the service in 2021/22, the highest level in at least a decade – which undermines the government by weakening institutional memory and creating risk for major projects and public services. The more than 123,000 civil servants at the most junior grade (AA/AO), for example, who are now on an average £21k a year amid the spiralling cost of living crisis, may well opt to leave the service in favour of better paid, equivalent roles in the wider public and private sectors.

And low pay will make it harder to recruit top talent into the civil service. This is a particular problem for the senior civil service, where recent IfG research has found that pay restraint has led to the SCS employment proposition becoming less attractive, especially for specialists. One recent example was the government’s three-year-hunt to recruit a chief digital officer, hindered by the inability to compete with equivalent roles outside the civil service.

In the context of widespread industrial action across government departments, it is important that ministers recognise the trade-offs at stake in holding down civil service pay. The civil service should not be immune to difficult financial decisions and must play its part in improving efficiency, but ministers risk finding themselves leading a demoralised and ineffective workforce unable to deliver their priorities.

- Topic

- Civil service

- Department

- Cabinet Office HM Treasury

- Publisher

- Institute for Government