EU Withdrawal Act 2018

We explain the legislation which allowed the UK to leave the EU, how much time was spent debating it and why it was needed.

What is the EU Withdrawal Act 2018?

In her first party conference speech as Prime Minister, Theresa May announced that the Government would introduce a ‘Great Repeal Bill’ to allow the UK to leave the European Union (EU). The ‘Repeal Bill’ was formally announced in the Queen's Speech on 21 June 2017 and had its first reading in the House of Commons on 13 July 2017 under its official title, the European Union Withdrawal Bill.

It was introduced with 19 clauses and eight schedules but by the time it received Royal Assent, nearly a year later on 26 June 2018, it had increased in length by 63% and is now composed of 25 sections and nine schedules.

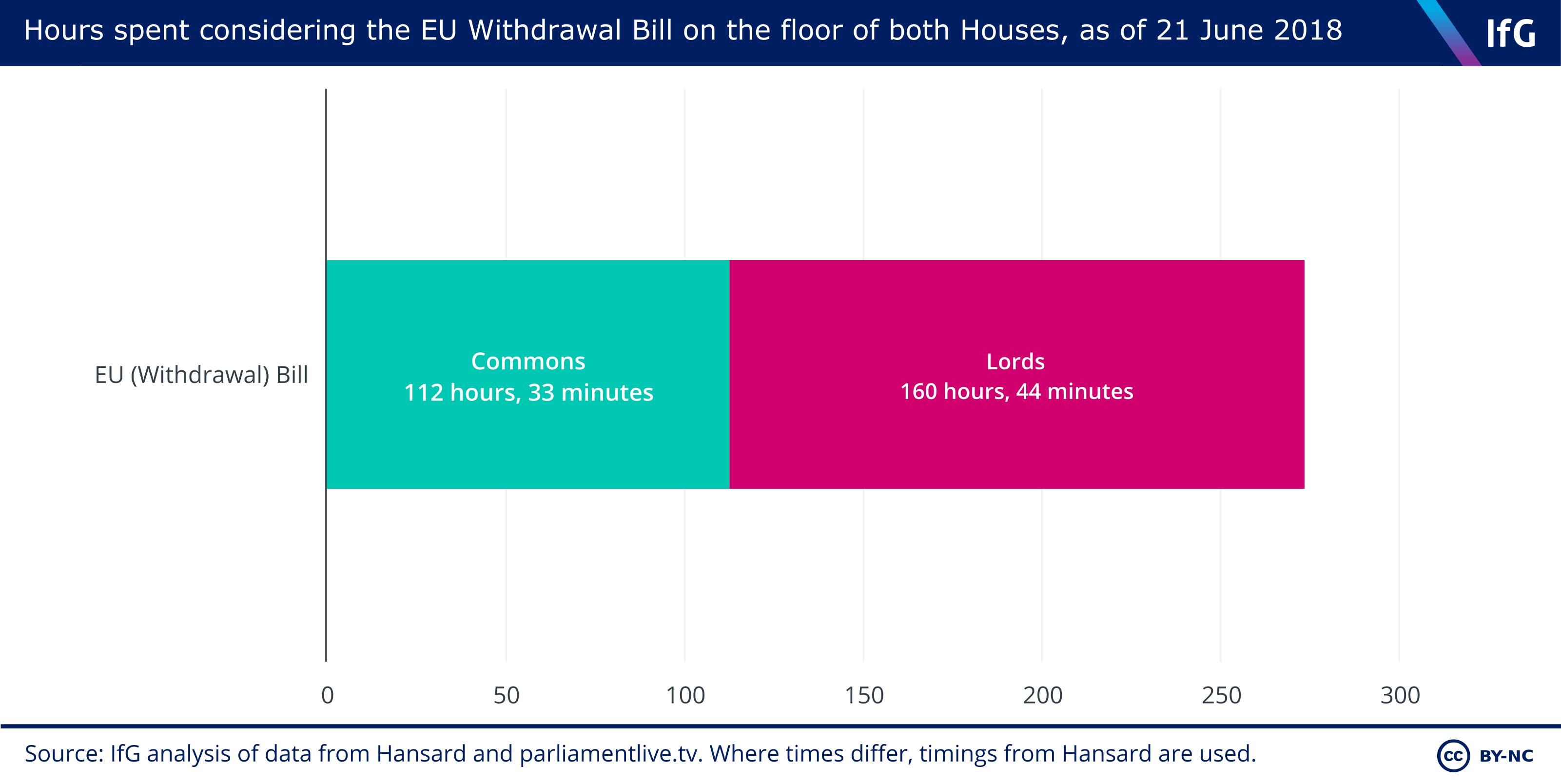

In total, Parliament has spent more than 272 hours debating the bill: 112 hours, 33 minutes in the Commons, and 160 hours, 44 minutes in the Lords.

What does it do?

The EU Withdrawal Act does three main things:

- Repeals the European Communities Act 1972. This legislation provides legal authority for EU law to have effect as national law in the UK. It does this in two ways:

- Some types of EU legislation – including treaty obligations and regulations – have direct effect in the UK’s legal system without the UK Parliament having to pass any further legislation. For example, safety standards on imported goods have been agreed at EU level and apply in every member country.

- Other types of EU legislation – including directives and decisions – can be made to apply in the UK either by primary legislation (Act of Parliament) or, much more commonly, by secondary legislation. For example, the Working Time Directive was implemented in the UK via the Working Time Regulations.

- Brings all EU laws onto the UK books.The Act is essentially a giant ‘copy and paste’ exercise. It means that laws and regulation made over the past 40 years while the UK was a member of the EU will continue to apply after Brexit. In doing this, the Act creates a new category of UK law: EU retained law.

- Gives ministers power to make secondary legislation. But the Act couldn’t just copy and paste EU laws unchanged onto the statute book. Many EU laws for instance mention EU institutions in which the UK will no longer participate after Brexit, or mention EU law itself, which will no longer be part of the UK legal system. There is not enough time for Parliament to make all these changes through primary legislation, so the Act gives ministers so-called ‘Henry VIII powers’ to make changes to both primary and secondary legislation using statutory instruments, which can get onto the statute book quicker as they are subject to less parliamentary scrutiny.

A new clause (Section 13) was added to the bill which sets out how Parliament will be involved in the process of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. It requires the Commons to both vote on a motion to approve the Withdrawal Agreement and political declaration on the future relationship, as well as pass the EU Withdrawal Agreement Bill to implement the agreement in domestic law.

Section 13 also sets out how Parliament will be involved if the UK faces a ‘no deal’ exit.

If the UK is leaving the EU, why is it keeping laws made by the EU?

EU law covers areas such as environmental regulation, workers’ rights, and the regulation of financial services. Without the Act, when the UK leaves the EU, all these rules and regulations would no longer have legal standing in the UK, creating a "black hole" in the UK statute book and leading to legal uncertainty and confusion.

By carrying EU laws over into UK law, the Government plans to provide for what David Davis, former Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union, called ”a calm and orderly exit” from the bloc, while giving the Government and Parliament time to review, amend or scrap these laws in future.

The purpose of the Act is to provide certainty and continuity, ensuring the same rules and laws apply immediately after Brexit wherever possible and supporting a smooth transition.

What were the areas of contention during its passage through Parliament?

During the bill's passage, the Government lost one vote during the Commons committee stage, after 12 Conservative backbenchers voted against an amendment which enshrined the Government’s commitment to implement the Withdrawal Agreement through primary legislation. After that, the Government managed to avoid further defeats in the Commons, although it made a number of concessions in doing so.

The bill was significantly amended in the House of Lords by both the Government and peers. For more detail on this, read our explainer on the key amendments and debates in the House of Lords.

There were three key areas of debate:

Delegated powers

The Act gives ministers wide-ranging delegated powers – it allows ministers to use statutory instruments to amend both primary and secondary legislation. This proved controversial during the bill’s passage and many amendments tabled by backbench MPs, and peers, sought to limit both what these powers could be used for as well as address how these powers would be scrutinised.

The Government did make concessions on these issues. For example, it agreed to include an exhaustive list of circumstances where these powers could be used, as well as remove a controversial provision in the bill which would have allowed ministers to use statutory instruments to amend the Act itself.

The Government also accepted amendments tabled by Charles Walker, Chair of the Procedure Committee, to establish a ‘sifting committee’ to assess whether a statutory instrument tabled under the negative scrutiny procedure should be upgraded to affirmative. The latter gives parliamentarians more opportunity for scrutiny. The European Statutory Instruments Committee was established once the bill got Royal Assent.

Devolution

The Government’s white paper on the ‘Great Repeal Bill’ committed to “intensive discussions with the devolved administrations” about how devolved policy powers repatriated to the UK from the EU will be managed by the four nations of the UK. Both the Scottish and Welsh governments agreed that, in certain policy areas, so-called ‘common frameworks’, or UK-wide agreements will be needed to prevent significant divergence across the four nations. But the detail of these is still undecided.

Therefore, it was extremely contentious that the bill, when first published, brought powers directly back to Westminster pending the outcome of discussions with the devolved administrations. Both the Scottish and Welsh First Ministers gave notice straight away that they would not be prepared to give legislative consent to the bill “as it stands”, labelling it “a naked power grab”.

The Government has since reached a compromise with the Welsh Government. Rather than these powers returning to Westminster until the UK Government determines otherwise, powers will now return to the devolved administrations except in areas where UK ministers will use statutory instruments to say otherwise.

The Scottish Government refused to give legislative consent, under the Sewel convention, to the bill, but the UK Government passed it anyway arguing that the circumstances were ‘not normal’.

‘Meaningful vote’ and no deal

An issue which became increasingly prominent during the bill’s passage was whether Parliament would have a ‘meaningful vote’ on the final Brexit deal. The Act requires MPs to vote on a motion to approve the Withdrawal Agreement and political declaration on the future relationship, as well as pass a bill to implement the Withdrawal Agreement, before the Government can ratify the deal with the EU.

There were a number of amendments and counter-amendments during the bill’s passage about what role Parliament should have if the UK faces a ‘no deal’ exit. The final wording in the bill requires ministers to make a statement to Parliament setting out next steps if:

- Parliament rejects the deal

- if agreement can’t be reached with the EU

- or if there is no deal by 21 January.

For more detail read our explainer on Parliament’s meaningful vote on Brexit.

- Keywords

- Withdrawal Agreement

- Publisher

- Institute for Government