A bill to reduce homelessness is about to become law. Sophie Wilson examines the unique role played by a Commons select committee in helping it succeed against the odds.

Private members’ ballot bills rarely become law.

The Homeless Reduction Bill was introduced as a ballot bill in June 2016. Bob Blackman, the sponsoring MP, gained this opportunity through the ‘ballot’ – a prize draw for backbench MPs that provides 20 MPs with an opportunity to introduce legislation each year.

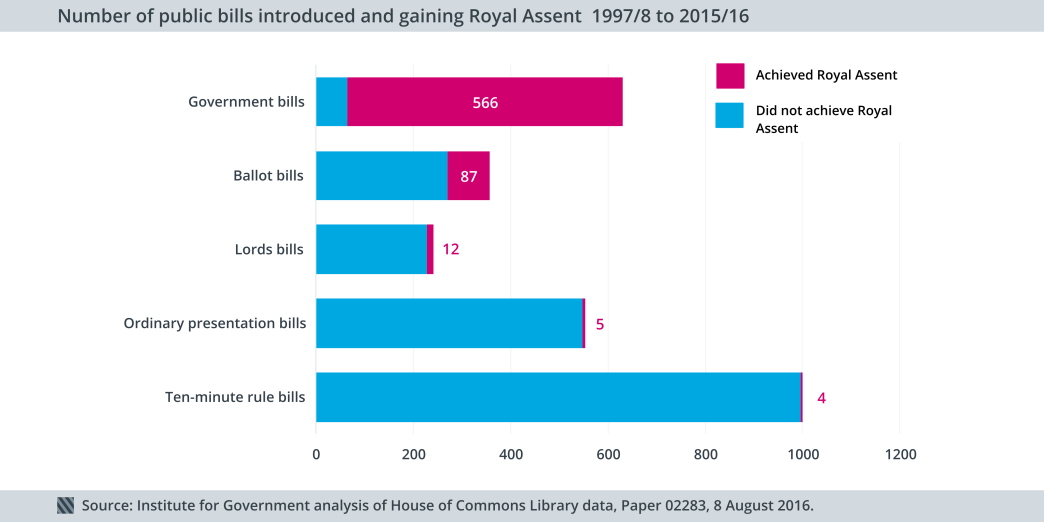

That the bill is now about to become law is an impressive feat. On average, fewer than five ballot bills become law each session. Since 1997, only 24% of all ballot bills (87) have gained Royal Assent compared to 90% of government bills.

Innovations in select committees can provide a helping hand.

Blackman sits on the Communities and Local Government (CLG) Committee, a cross-party group of MPs responsible for scrutinising the work of the Department for Communities and Local Government. Blackman, and the CLG Committee, effectively used this position to up the odds of taking the Homelessness Reduction Bill from an idea to law.

This is the first time a select committee inquiry has directly led to legislation through a ballot bill/private member's bill. It illustrates how parliamentary innovation can result in real change: the bill requires councils to provide support for people threatened with homelessness 56 days in advance rather than 28 days as it currently stands.

How they did it.

By using the options available within Parliament in a new and creative way, Blackman and the CLG Committee were both able to influence the Government and maximise their impact.

- Before Blackman won the ballot, the committee launched an inquiry into homelessness, taking evidence and going across the country to hear from those who had been directly affected by homelessness. The conclusions from this inquiry formed the basis of Blackman’s bill, giving it a step up with a strong evidence base and a ready-made network of stakeholders.

- The committee built cross-party support for the bill. Committee members from across the House helped by co-sponsoring the bill, sitting on the Public Bill Committee considering the bill and mobilising colleagues from both sides of the aisle. The process of reaching consensus between diverse committee members during the inquiry process stress-tested the conclusions, illustrating the political feasibility of the recommendations and made them harder for the Government to ignore.

- The committee conducted a second inquiry into the draft Homelessness Reduction Bill itself. Conducting pre-legislative scrutiny into the bill provided a further opportunity to garner views from stakeholders and strengthen the legislation. This is something the Government recognised when it announced its support for the bill.

Drawing upon the experience, expertise and relationships, the committee helped the bill defeat the odds.

Can other select committees do this?

Parliamentarians should be thinking outside the box. Understanding how the Homelessness Reduction Bill became law might be a fruitful source of inspiration for MPs and select committees alike. For example, committee MPs should consider the following:

- Are you making the most of the parliamentary opportunities available?

- Can you join up with others across Parliament?

- How can your committee use the inquiry process to compliment and feed into work across the House?

Legislation will not often be the desired outcome for a select committee. But creatively responding to the wider context and seizing upon opportunities as they arise, may turn the odds of impact in your favour.