Graham Atkins argues that the next government must limit policy uncertainty if it wants to secure best value for consumers.

In the rush to end the parliamentary session, two important but little-noticed select committee reports were published: the Commons Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Committee’s report on energy policy, and the Lords Science and Technology Committee’s report on nuclear research and technology.

The two reports highlight vital energy issues. Investing in new low-carbon energy infrastructure is critical: without new investment, the UK will struggle to keep the lights on – not to mention meet its emission targets. Policy uncertainty hinders this process. It is therefore vital that the next government reduces it as far as possible to ensure that the costs of these investments are manageable. There are two critical steps the next government must take:

1. Be clear about Brexit

The biggest Brexit energy question is how long the UK will remain part of Euratom, the nuclear research, training, and regulatory body. This matters. Policy uncertainty means investors will either decrease or delay investment, or ‘price in’ uncertainty by seeking a higher return which, ultimately, means higher taxation or higher energy bills.

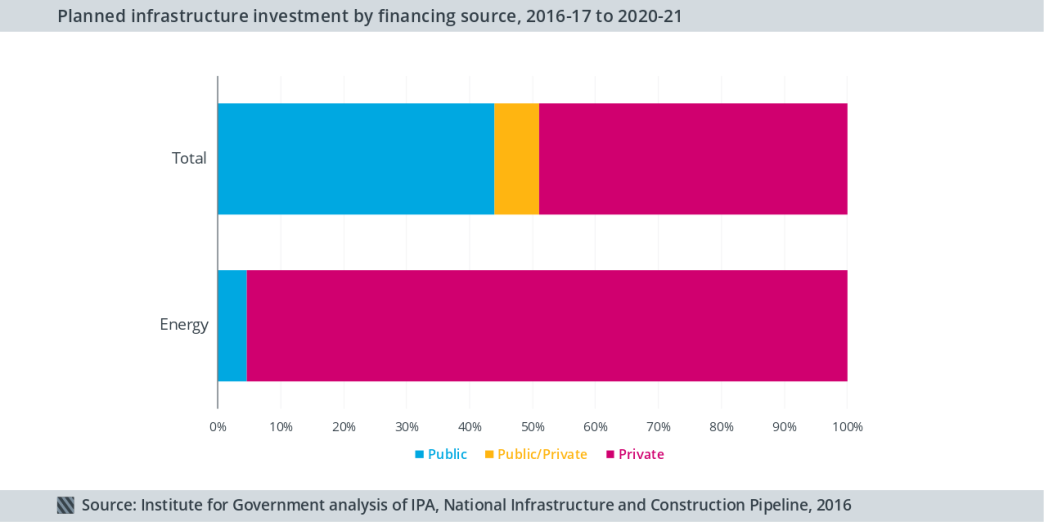

Uncertainty is particularly important in energy because we rely heavily on private finance to support investment in energy infrastructure. According to the Infrastructure and Projects Authority’s pipeline, 95% of planned energy investment over the next five years is to be financed by the private sector, which is much higher than in other sectors.

Anecdotal evidence submitted to the BEIS Committee suggests that concerns have been exacerbated since the vote for Brexit. Chatham House estimates that incoming investment may have declined by 10% following the EU referendum, and the National Grid estimates that even minor increases in financing costs could increase consumer bills by “hundreds of millions”. The UK has also tumbled from eight to 14 on EY’s ‘Renewable Energy Country Attractiveness Index’.

Some uncertainty is inevitable, but the next government needs to outline and communicate its plans to investors early on. In the absence of engagement and a clear plan, conflicting messages or a communication ‘void’ will increase the cost of infrastructure.

2. Make a decision about nuclear power

Failure to commit to a civil nuclear strategy – a plan for domestic nuclear power – will hinder the UK’s ability to develop low-carbon energy. Much like it has with the institutions required for a successful industrial strategy, the UK has procrastinated on whether to support small modular reactors – nuclear power plants with outputs of 300MWe or less, designed for mass manufacture.

Given their development costs, these reactors require government support. But investors and industry have been left in the dark. Rolls Royce, for example, are still seeking clarity from BEIS on whether a competition for designs – initially planned for completion in Autumn 2016 – will go ahead.

BEIS have also yet to publish their techno-economic assessment of small modular reactors, although the report was completed last year. It is legitimate for the Government to assess the costs and benefits of supporting research in highly-uncertain future markets. But delay and opaqueness have become overwhelming. Endless procrastination is the same as choosing to kill a project, but without ensuring it is the right course of action.

Exploring the issues

The debate over small nuclear projects illustrates a wider issue the next government needs to tackle head on: whether smaller projects offer better value for money. In nuclear, there is considerable debate on big versus small projects. Small projects have lower absolute capital costs – and are likely to have lower financing costs if a pipeline of ‘proven’ projects comes forward. Small projects are also likely to be less ‘fragile’ – less likely to become unrecoverable due to a random event – than megaprojects, although they are unable to provide the same level of energy.

There are good arguments on both sides, and the debate extends beyond the energy sector: utilities, transport, and communications face similar discussions. The next government needs to recognise this debate, and consider the merits of big versus small options – rather than defaulting to the excitement of ribbon-cutting and ‘shiny new things’.

We will explore in greater depth whether bigger projects are better than small projects at our event on the 10 May, ‘Success in infrastructure: are bigger projects better?’