Three ways that the coronavirus crisis has changed government

The new Whitehall Monitor 2021 report sets out the immediate impact of the pandemic across government, writes Alice Lilly

The long-term political, economic, and social consequences of coronavirus are only just coming into focus. But the new Whitehall Monitor 2021 report sets out the immediate impact of the pandemic across government, writes Alice Lilly

At the end of 2019, Boris Johnson’s government had a new and large majority, had reached an exit deal with the EU, and was turning its attention to its ambitious manifesto pledge to ‘level up’ the UK’s economy. Then everything changed. The coronavirus crisis has massively changed how the government spends money, how it takes decisions, and how it shapes policy.

Government has made and implemented policy at unprecedented speed

First, ministers and officials have had to make policy choices and then implement those decisions – at a much faster pace than is normal. For example, the furlough was developed by the Treasury within just a few weeks – and became operational within a month of its announcement. Between March and December 2020, new digital systems to administer the furlough, statutory sick pay, and self-employment programmes managed payments worth more than £69.4 billion.

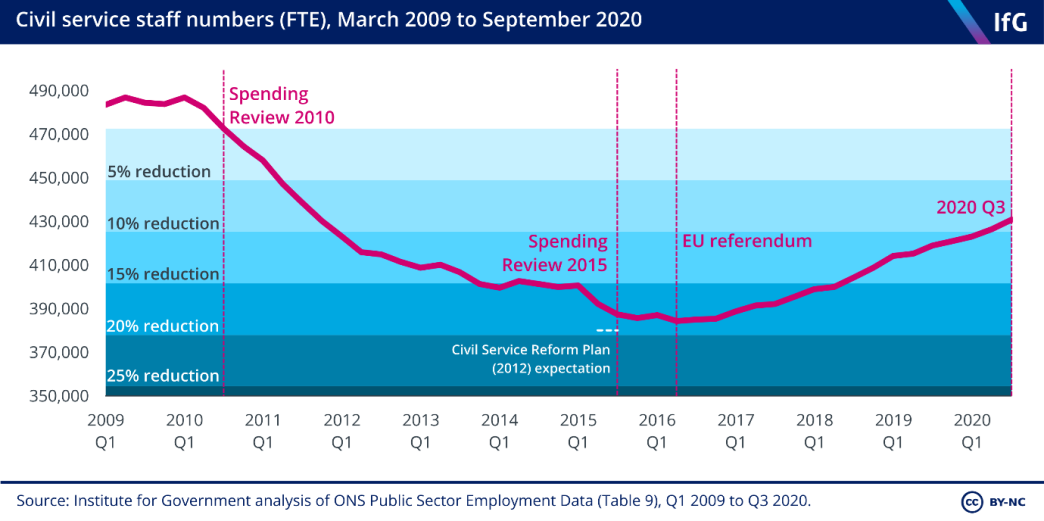

Delivering these new systems has shown the civil service at its best: able to manage crises and deal quickly with changing priorities. It has rapidly recruited additional staff in key departments: the Department of Health and Social Care, for example, grew by almost a quarter in the first nine months of 2020. At the same time, drawing on lessons learned from several rounds of no-deal Brexit preparations, the civil service has quickly redeployed staff to meet the challenges posed by the pandemic.

This has also highlighted problems within the civil service, with ministers and senior civil servants pointing to a lack of readily available skills in some key areas, such as procurement, digital, and science and engineering. To address this expensive use has been made of consultants: over £175m has been spent on 90 consultancies and companies during the pandemic. All of this has reinforced ministers’ desire to reform the civil service—at the same time as the pandemic has forced the issue further down the agenda.

Ministers have been prepared to spend far more than planned

When the new chancellor, Rishi Sunak, delivered his first Budget in March 2020, the pandemic was yet to be a major crisis. But within days, the government’s plans for the public finances were effectively ripped up.

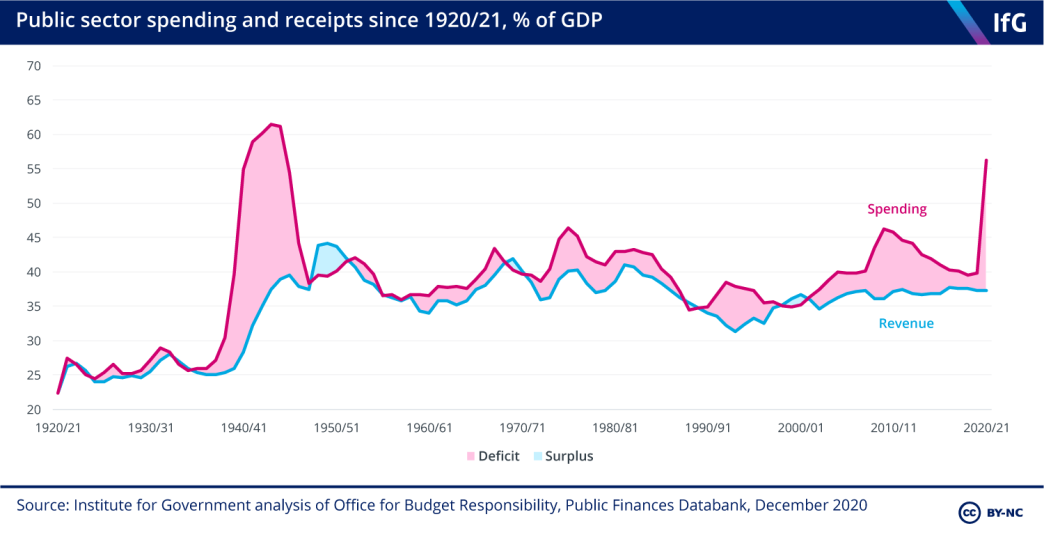

Ministers stepped in to address the economic effects of lockdown on households and businesses, as well as to support public services. Government spending this year will be £200bn more than last year—reaching over £1 trillion for the first time. At the same time, tax revenue has fallen to its lowest point in a decade. The cost to the public purse has been huge. Originally, the government planned to borrow £55bn this year. Instead, public sector borrowing is forecast to top £394bn, or 1% of GDP—the highest since the Second World War.

Although the Treasury and HMRC have quickly developed policies to combat the economic challenges posed by coronavirus, questions persist about the value for money of these schemes. Like the government’s approach to procurement, a quick-fix strategy for economic policy in the early stages of the pandemic made sense. But ministers have persisted with policies like the Bounce Back Loan Scheme even where evidence suggests that they aren’t offering good value for taxpayers.

It is also unclear what this will mean for public finances in the future – and how ministers will pay for such a huge expansion of public borrowing.

Government has communicated more directly with the public

As a public health crisis, the pandemic has required ministers and officials to communicate more directly—and more frequently—with the public. Updates, major decisions and changes to restrictions – like the first lockdown, the lockdown exit strategy and the ‘rule of six’ – have been communicated directly to the public via televised press conferences during prime viewing hours. At their peak, press conferences were watched by 27.5 million people.

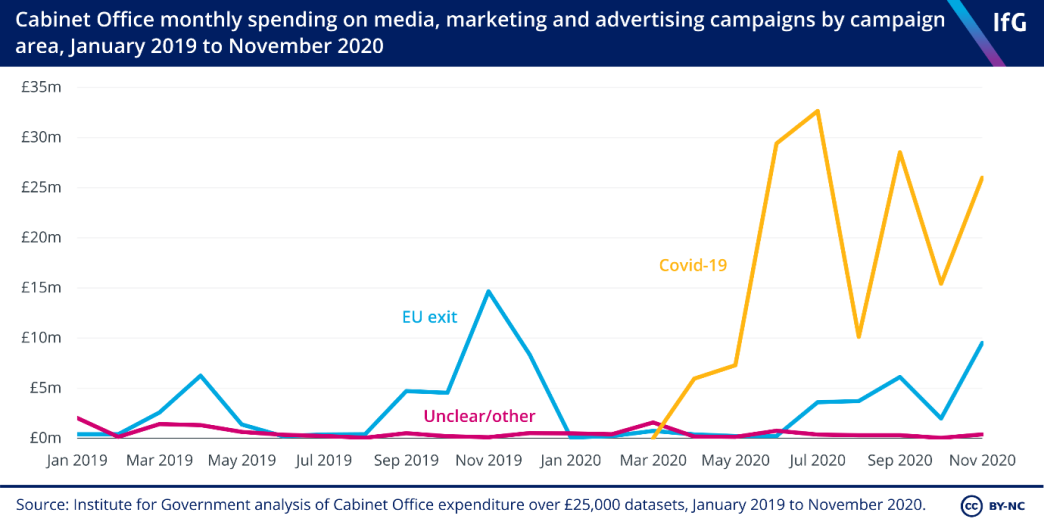

Ministers have also spent far more on advertisement and public information campaigns than in recent history—even including campaigns to prepare businesses and the public for Brexit. At the height of Brexit preparations in 2019, the Cabinet Office spent almost £15m on advertising – but in summer 2020 alone, it spent double that on coronavirus-related adverts. This has meant that the public has seen and heard government information much more frequently than before: 95% of adults have reportedly been reached by public information campaigns an average of 17 times.

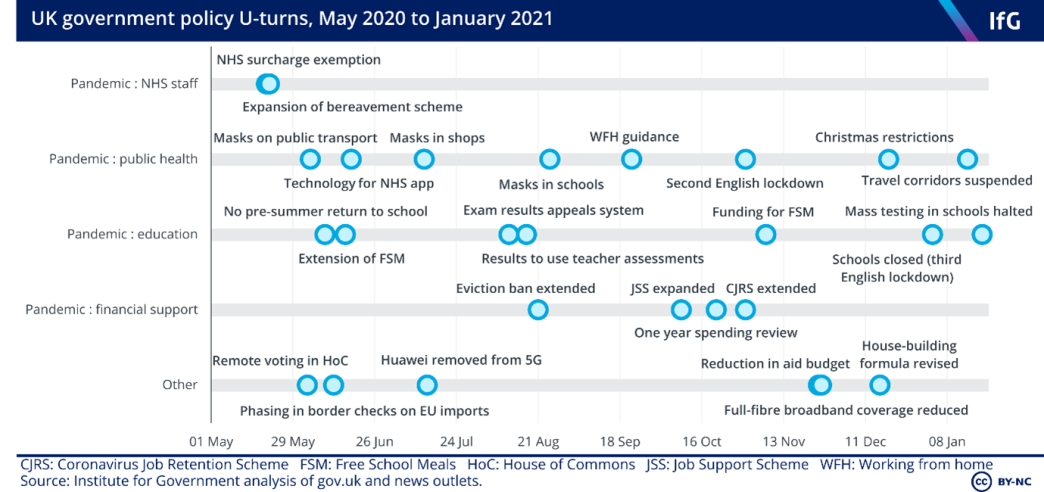

But quantity and quality of communication are not the same thing. At times, the government’s messaging has been confused and contradictory, with repeated u-turns, including those which involve a welcome correction to policy, have further created confusion and frustration among the public.

Government will need to draw the right lessons from the pandemic

The pandemic has not gone away – as underscored by the grim milestone reached this week of over 100,000 deaths in the UK. The third lockdown is set to continue until at least March, and although the rollout of the vaccines offers some hope for the future, coronavirus is set to be a major part of life for the rest of the year.

Ministers and officials must reflect on how government has changed its ways of working, and the lessons that they can draw from this. By acknowledging areas where government has successfully done things differently – as well as places where its approach has been unhelpful or counterproductive – it will be better equipped to deal with the next phase of the pandemic and to achieve its other priorities in 2021.

- Supporting document

- whitehall-monitor-2021.pdf (PDF, 5.68 MB)

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Department

- Cabinet Office

- Publisher

- Institute for Government