The heat and buildings strategy shows the government is grappling with the right problems

The government's long-awaited plan to decarbonise homes is big on heat pumps but curiously silent on energy efficiency

The government's long-awaited plan to decarbonise homes is big on heat pumps but curiously silent on energy efficiency, says Will McDowall

Net zero will require a complete transformation of the way homes are heated in the UK, with some 85% of households currently using a natural gas boiler. But uncertainty about future technology costs and developments make decarbonising homes among the most difficult policy problems facing the government. It is also fraught with political risks: the recent furore over spiralling energy prices showed how quickly issues that directly affect people’s lives, and in this case homes, can dominate the public agenda.

So the publication of the long-awaited heat and buildings strategy is welcome. It recognises the need to take proper account of technology development, skills and market design – but also regulation, taxation and fuel poverty. This is encouraging. The government may not have found all the answers, but it is grappling with the right problems.

Some real progress is promised on heat pumps – but many questions remain about delivery

Most analysts view electric heat pumps as an essential part of a low-carbon heating system, even if much of the country converts to the main alternative, hydrogen boilers. But the UK’s history on deploying heat pumps has been dismal compared with many European neighbours (heat pumps can be found in around half of detached houses in Sweden). The low costs of both gas and gas boilers have meant that the heat pump market has never taken off here, despite years of subsidy through the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI).

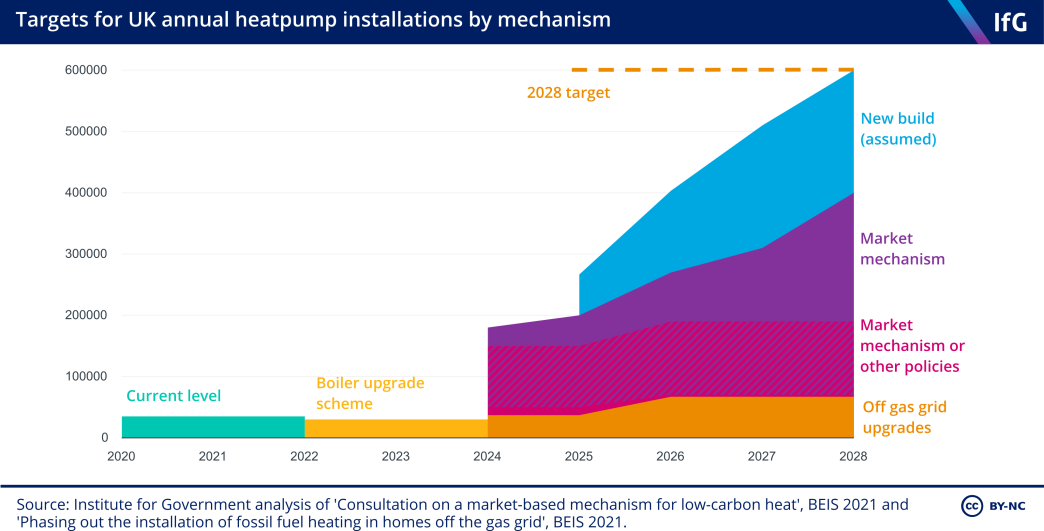

The strategy sets out a new set of policies designed to drive the adoption of heat pumps, largely through regulation rather than public spending. Headlines have focused on the £450m ‘boiler upgrade scheme’ – a £5,000 subsidy for consumers that replaces the RHI. But the scheme is limited to three years and only 90,000 heat pumps, a figure dwarfed by the government’s target of 600,000 a year by 2028.

There is no firm commitment to phase out the installation of new gas boilers by 2035, with a watered down ‘ambition’ enabling the prime minister to say that nobody will be forced to rip out their boiler. But the regulations announced do have the potential to drive a serious expansion of the heat pump market and are probably more meaningful than a distant phase-out: a ban on the installation of fossil-fuelled heating systems in homes off the gas grid from 2026 is likely to nearly double the UK’s current heat pump market overnight. A proposed ban on the installation of natural gas boilers in new homes from 2025 is even larger, generating perhaps 200,000 heat pump installations annually from around 2027 according to business department projections.

In addition to these regulations, the department is planning to introduce a major new policy to transform the heating market: a ‘market-based mechanism’. This would place an obligation on boiler manufacturers to sell a certain number of heat pumps as a proportion of their boiler sales (conceptually similar to the Renewables Obligation or the Zero Emission Vehicles mandate).

The government’s heat pump target falls short of the Climate Change Committee (CCC)’s proposed pathway, but represents a step-change in deployment rates. Using the numbers in the government’s impact assessments, we have estimated the deployment it expects from these policies (see below). the development of technology and the potential of other policies—including a proposal to shift policy costs away from electricity bills and onto gas—with the ‘market mechanism’ expected to pick up the slack if those policies do not deliver. If it goes through with the planned market mechanism for heat pumps, it has a credible pathway to accelerating heat pump deployment to a level close to what is required for net zero.

But there remain big questions about whether this can be achieved. The ‘market-based mechanism’ has not been fully costed, nor is it clear where the costs will fall. Much of the design has yet to be decided, and little substantive thought appears to have gone into oversight and delivery. The strategy suggests only that Ofgem may be responsible, as the government’s default energy policy delivery agency. A key test of the strategy’s credibility over the coming year will be whether the government can translate its market-based mechanism from an idea into a workable plan.

The strategy makes too little progress on energy efficiency

There is no announcement on promised regulations to drive upgrades in the private rented sector despite consultations concluding months ago. Public spending on energy efficiency is being carefully targeted at public sector buildings, those in fuel poverty, and social housing – and anyway amounts to much less than promised in the Johnson government’s 2019 manifesto. That leaves an increasing policy gap, particularly around owner-occupied buildings – the single largest tenure type. The strategy provides no clear plan for driving efficiency in these houses, other than some nudges to encourage mortgage lenders to ‘green’ their portfolios.

This is a strategy that is ambitious on new technologies, where there are big uncertainties, and tentative on the areas where progress is essential and understood – if dull. The government should recognise that both are vital if it is to hit its net zero target.

- Supporting document

- public-engagement-net-zero.pdf (PDF, 377.27 KB)

- Topic

- Policy making Net zero

- Publisher

- Institute for Government