Former No.10 Policy Unit head Camilla Cavendish has been talking dirty on Radio 4 – specifically on the need to clean up our dirty air. But Jill Rutter says the problem of diesel has been around much longer than a few weeks of high alerts for poor air quality.

Clean air versus less carbon

One of the classic pieces of tax policy intervention was Nigel Lawson’s decision in the 1980s to levy a surcharge on leaded petrol. Despite concerns at the time that motorists would fill up their engines with the wrong petrol and wreck their engines, it achieved a very rapid switchover, to the great benefit of air quality.

A few years later, the policy concern switched to climate change, and the issue become not leaded versus unleaded, but petrol versus diesel – or clear air versus less carbon. In the early 1990s, HM Treasury toyed with a diesel incentive – until the senior official in charge of tax policy inhaled a lungful of diesel fumes on the way to work and argued persuasively that it would be the wrong way to go.

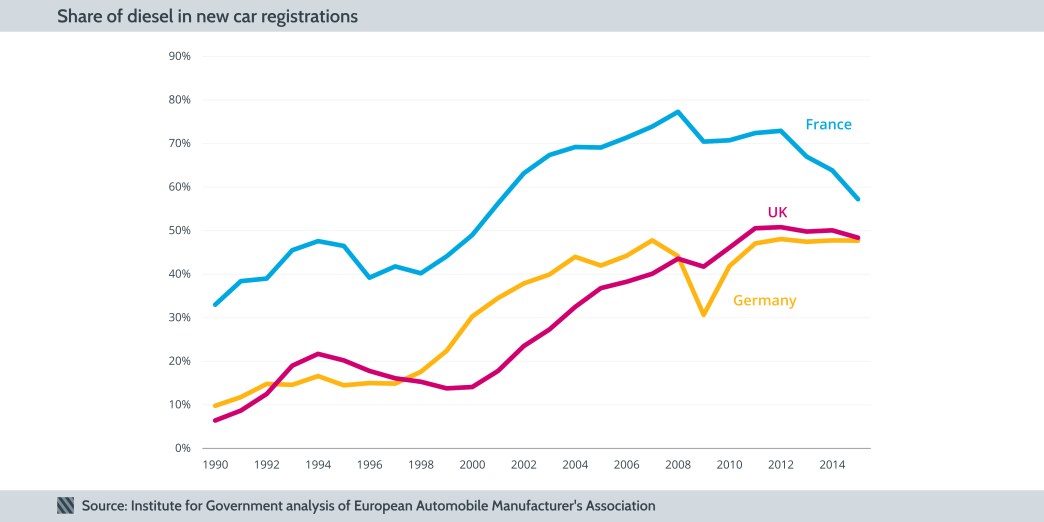

Roll on to the 2000s and climate change went up the political agenda. European regulation was supposed to deliver cleaner diesels which trapped particulates and cut nitrogen oxide emissions. Car taxes were tweaked to favour diesel, even though the UK never introduced the big fuel duty incentives seen elsewhere. That helped fuel (pun intended) a dramatic growth in the market share of diesel over the last 25 years.

At the same time, Europe was agreeing to ambitious air quality targets, and studies linked poor air quality to premature deaths. Many EU member states are finding those targets, agreed without clear plans to meet them, tough. The UK Government has been taken to court over its failure to meet air quality targets and has been ordered to produce a plan to meet them by the summer.

But what does this tell us about policy making, the theme of Baroness Cavendish’s radio piece?

The first problem is one of objectives.

If you give primacy to climate change and diesel, then fewer carbon emissions per mile look better. But if you favour better air quality, then petrol is your best choice.

Air quality has much more immediate impacts than climate change, but during the 2000s, the momentum behind the environment movement built and climate became the leading issue. So, government policy swung behind climate objectives, with air quality paying the price.

The creation of the Department of Energy & Climate Change, and now the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, means that climate change and energy policy sits in one department, with air quality in another. Meanwhile, the Department for Transport has often been, under various secretaries of state, a defender of motorists, and the business department promoted the automotive industry. Interestingly, some of the ministers responsible at the time denied that they ever were asked to make an explicit choice.

Secondly, where does responsibility for action best sit?

Air quality is a localised problem – climate change the ultimate global one. National policy measures are better at targeting the global than the local. If people are using cars to drive long distance, with relatively little city driving, diesels are still better. But if they are not, the better choice is petrol.

As the Financial Times has argued, giving local government powers may be a good way to get the right policy mix. London already exempts electric cars and hybrids from the congestion charge. Westminster is experimenting with a diesel parking surcharge. In other cities, mayors have powers to ban cars when pollution levels are too high.

Regulation and proper enforcement matters.

European Commission standards were supposed to square the circle between air quality and climate change. But failure to test whether vehicles met the standards when driven in normal conditions meant they fell well short of expected benefits. Even now, countries including the UK and Germany are in court for failing to take sufficient action against manufacturers.

Regulation has a bad name, but it is regulation that cleaned up the air in the 1950s and has led to other improvements of environmental quality.

So what happens now?

Can we get out of the mess created by policy choice and regulatory laxity?

A lot of diesel drivers will feel they did no more than respond to the incentives they were offered. Car drivers are a big constituency, and governments are notoriously reluctant to interfere with the right to drive.

But air breathers are an even bigger, if until recently, less organised group.

A response to air pollution which tells vulnerable people to stay inside and children not to play appears to be more politically acceptable than one that tells drivers to choose a temporary, alternative means of transport. It is also less costly than a full-blown diesel scrappage scheme, though officials are reportedly looking into this now.

But at the root of this entire policy are the cumulative decisions over decades that successive governments have made about whose interests have primacy in our cities. The air quality debate that Baroness Cavendish highlights will serve a useful purpose if it causes us to re-examine in whose interests our cities are governed.

- Topic

- Policy making