Clinton’s defeat and the experience of women leaders in the UK

Nicola Hughes digs into our Ministers Reflect archive to look at the experience of women leaders in the UK

As the world reacts to Donald Trump’s victory in the presidential race and considers what role misogyny played in Hillary Clinton’s defeat, Nicola Hughes digs into our Ministers Reflect archive to look at the experience of women leaders in the UK.

“I know we have still not shattered that highest and hardest glass ceiling,” said Clinton in her concession speech on Wednesday, “but someday, someone will, and hopefully sooner than we might think right now.” I for one had a lump in my throat. Like her or loathe her, a Clinton victory would have been a huge moment for women and, one hopes, inspired more girls and women across the globe to get involved in politics. The reasons for her defeat are more varied and complex than gender alone, but it’s hard not to think that American voters simply weren’t ready for a woman Commander-in-Chief or that, as Julia Gillard spoke about recently, unconscious bias as well as overt sexist attacks influence the way we see women leaders.

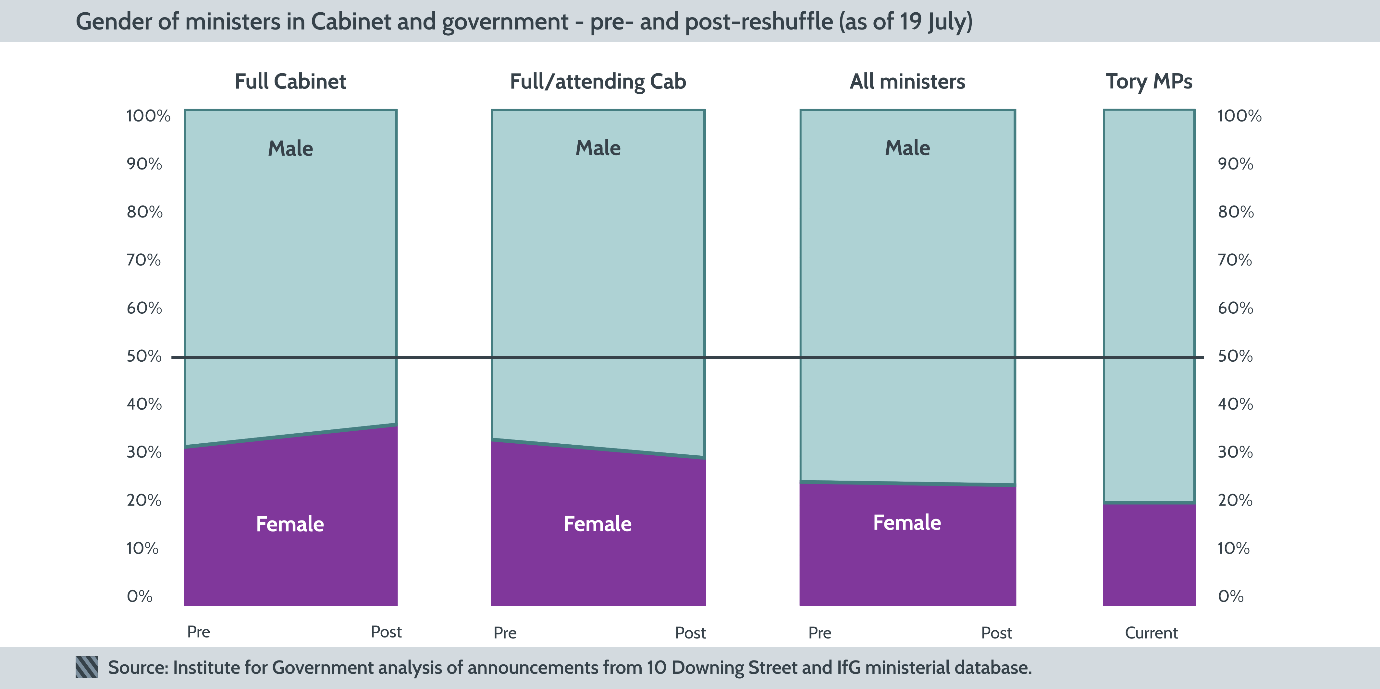

At home, women like Theresa May and Nicola Sturgeon are showing that politics needn’t be dominated by men, yet UK politics is still not reflective of the population at large (including on ethnic diversity and disability, but let’s focus on gender for now). The UK ranks 49th in the world in terms of women’s representation in Parliament and just 29% of our MPs are women. The paucity of women in Parliament means a narrow field from which to recruit women ministers: as the chart below shows, less than a quarter of all current UK ministers are women.

Female role models

Ministers Reflect interviewee Jo Swinson considered the effects of this lack of diversity when we asked her about role models in government: “I think one of the difficulties is, and it’s not as if you can’t have a male role model, but it is just easier as a woman to look at other women. And of course there are not that many women minsters.” On first arriving in government she recalled:

“…looking around at people that I knew that were minsters who were mainly guys and the way in which they did it with, in some cases, a certain degree of swagger or a degree of alpha male syndrome in government and just not really feeling like that was me.”

Gender assumptions

Other women ministers felt that gender assumptions were loaded against them from the start. Jacqui Smith was the first woman to be Home Secretary. She dealt with a terrorist attempt in her first week on the job in 2007, and recalled the reaction to her response:

“The thing that people most often said to me about my public performance that weekend was ‘You appeared… you seemed very calm and reassuring.’ Now there is a certain subtext there, which is ‘You were the first female Home Secretary and you know, I think we partly thought you would go in, there would be a terror attack and you’d come out shouting ‘I can’t manage it, bring a man in.’”

Her colleague Margaret Beckett – whose interview transcript we will be publishing next week – was the UK’s first, and so far only, female Foreign Secretary. The US is slightly ahead here – Madeleine Allbright, Condoleeza Rice and Hillary Clinton herself have all been Secretary of State. Like Smith, Beckett was surprised by outdated attitudes to her appointment:

“I remember one of the women, a fairly senior woman, saying to me ‘You do realise that there are people in the Foreign Office who don’t think a woman should be Foreign Secretary?’ Which at that stage in the day would never have occurred to me.”

Patricia Hewitt described the well-intentioned but ultimately misguided assumptions of the Prime Minister about women ministers, like how her team came together when she became Health Secretary:

“Tony rang me and said, ‘Oh, I’ve got a really good team for you’, reads me out a list of names… and they were all women. I said, ‘Tony, you’ve given me an all-women team.’ He said, ‘Yes, I thought you’d be pleased’, and I said, ‘Tony, I don’t want health stereotyped as only about women.’ He said, ‘Oh! I thought you were a feminist, I am going to tell John Prescott on you.’ [laughter] I told him there’s a lot of evidence that mixed teams work better…”

Family life

Our women interviewees were not alone in relaying the pressure of ministerial life on family: male interviewees also talked about juggling small children and red boxes. But as former Treasury Minister Kitty Ussher explained, ministerial jobs are not quite like other jobs and when she took maternity leave in 2008, while her career was “at its peak,” there were issues to work out. She also felt her prospects suffered:

“When I came back, I got reshuffled and replaced by two men, when I didn’t want to move, so I suspect there was a longer term effect that weakened my position, which was frustrating.”

Back from leave with “a new born baby with its own routine that only mothers can deal with”, Ussher found time management was crucial and reflected on the typical image of a departmental minister: “a kind of stiff upper lip middle aged gentleman who would have Sunday lunch with his family and then his wife would take the children off… that was the image in my mind of what this system was supposed to be for. It would not be designed like that if you were starting again.”

Women’s policy issues

On a more positive note, women ministers have used their positions to advance women’s issues in government. Clinton has of course been a long-time advocate for women’s rights, while Trump’s policy positions on abortion, equal pay and childcare are still an unknown quantity. Hewitt, Smith, Swinson and several of our other interviewees held the Women and Equalities brief at different times in office. This role is usually combined with another portfolio and tends to move around from department to department following its Cabinet lead. Tessa Jowell “…did quite a lot of European negotiation and I was incredibly proud of the success I achieved in that, in particular negotiating the basis for the Equalities Act.” A later holder of the post, Lynne Featherstone, highlighted some of her achievements and the way that it enabled her to get women’s issues on the agenda, including female genital mutilation (“everyone wanted in on that”) and body confidence.

So the experience of women ministers in British government, based on our interviews, has largely been positive – they enjoyed their time in government, got things done and were not inhibited by the fact that they were women. But there were also instances of prejudice bubbling under the surface and a sense that Westminster and Whitehall systems are still somewhat old-fashioned. We can but hope that a female Prime Minister, if not a female President of the United States, will help encourage more women to be MPs and ministers. But the US experience suggests that sexist attitudes in politics are, sadly, not yet consigned to the history books.

- Topic

- Ministers

- Keywords

- Diversity and inclusion

- Country (international)

- United States

- Political party

- Conservative Labour Liberal Democrat Scottish National Party

- Series

- Ministers Reflect

- Legislature

- House of Commons Scottish parliament

- Public figures

- Theresa May Nicola Sturgeon

- Publisher

- Institute for Government