Johnson’s new chief whip has work cut out to tame a party with a taste for rebellion

The prime minister’s mini-reshuffle may be too little, too late to meaningfully improve Johnson’s relationship with his own backbenches

The prime minister’s mini-reshuffle may be too little, too late to meaningfully improve Johnson’s relationship with his own backbenches – putting the government’s agenda at risk, says Alice Lilly

The latest stage of the prime minister’s ‘reset’ focused squarely on repairing relations with his own backbenches, as he made changes in the two ministerial roles most involved in parliamentary management: chief whip and leader of the Commons. But this may not prove enough to secure his own future – nor bring his party into line.

The new chief whip faces a rebellious parliamentary party

Johnson’s problems with his own MPs have become worse in recent months, following a steady stream of controversies around standards and behaviour in government. But the prime minister has actually struggled with his parliamentary party ever since the 2019 election.

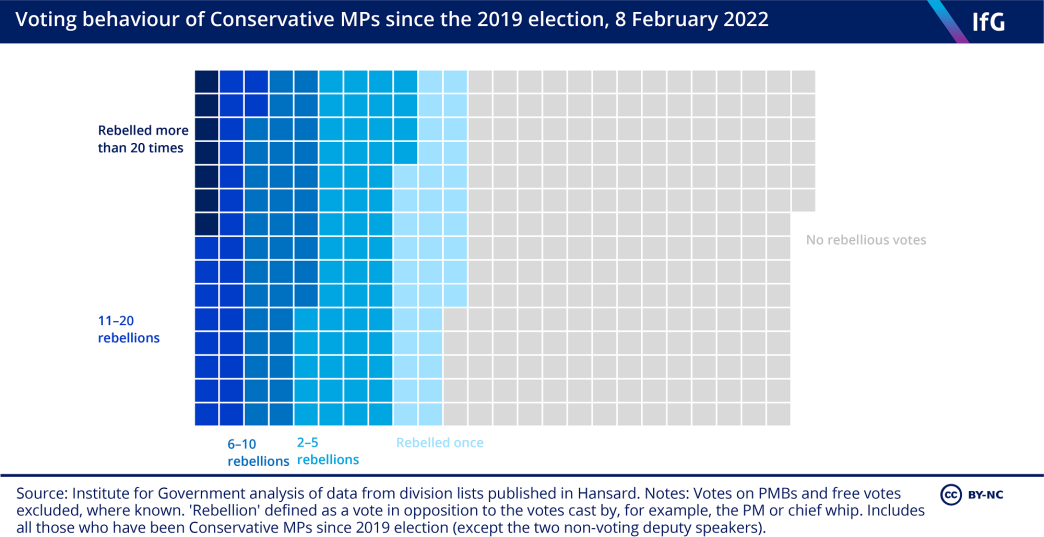

Voting lists in the Commons show how relations between the government and its MPs have broken down – and the scale of the problem facing Chris Heaton-Harris, the new chief whip. Almost half – 44% – of all Conservative MPs have rebelled at least once since the 2019 election, and most of those MPs have rebelled multiple times. Rebellions have not just been confined to Brexit or to Covid, either – they’ve also affected legislation such as the Fire Safety or Police and Crime Bills. And rebels have not come from just one wing of the party: rebels have included long-serving MPs with little previous history of voting against the government, as well as members of the 2019 intake.

Of course, the size of Johnson’s majority means that MPs know they can rebel without risking bringing down the government – meaning rebellions are arguably more likely under majority governments. But there was no parliamentary honeymoon for the prime minister, as you would usually expect. Rebellions have come thick and fast since the election: at least one Conservative MP has voted against the government in roughly a quarter of all divisions. Compare that to the last time a government was elected with a clear Commons majority, in 2015: just 18% of backbenchers rebelled in the first session of that parliament.

Backbench dynamics are changing

Some of these rebellions clearly result from policy disagreements – especially on Covid restrictions. But the frequency of rebellions from across the party on such a range of issues indicates that something else is also happening. Backbenchers are becoming more comfortable with voting against the government.

The experience of wielding power from the backbenches during Theresa May’s minority government showed MPs that they could exert influence – something hard to leave behind. And the move to hybrid working in the Commons during the pandemic made it harder for whips to build and maintain relationships with MPs, especially the 2019 intake. But the government doesn’t seem to have noticed these shifting dynamics. Instead, they have committed the cardinal parliamentary sin: assuming that, with a large majority, they can take the votes of their MPs for granted. Time and again, from the Owen Paterson debacle to the clumsy handling of cuts to overseas aid spending, the government has seemed surprised by the irritation on its own benches.

Changes may be too little, too late to meaningfully improve government–backbench relations

In the short-term, Johnson’s changes may be enough to head off an immediate threat to Johnson’s leadership. But his new appointments will have their work cut out – and there are several reasons to suspect these changes will not prove enough in the long term, either for Johnson or the government’s priorities.

First, Johnson has made relatively minor changes to the figures involved in the government’s parliamentary management. He may have appointed new chief and deputy chief whips, but other changes in the whips’ office have been minor. And Mark Spencer’s move from the chief whip role to leader of the Commons seems odd, given he has been the subject of repeated criticism (and some complaints) from backbenchers. who is under investigation by the independent adviser on ministerial interests over allegations of discrimination, will now play a role in the Commons’ standards processes – reportedly causing some discomfort on the Tory benches.

Second, these personnel changes may have come too late. Splits and squabbles among backbenches have become publicly visible, with one senior MP going so far as to accuse the now-leader of the Commons of blackmail, and others publicly calling on Johnson to resign. Returning to some sense of unity will be difficult, and so too will be reducing the scale and number of rebellions. Generally, once MPs begin to vote against their party, they find it easier to do so in future. With almost half the parliamentary party over that line, it will not be easy to get them back.

Third, Johnson’s outreach to his backbenches has so far only focused on fairly narrow groups: members of the 2019 intake (several of whom have been appointed as parliamentary secretaries to Johnson), as well as Brexiteers. But there are other parts of the party who he also has strained relations with.

The government risks seeing its agenda derailed

These changes may or may not be enough to save Johnson – but that is not the same thing as making long-term progress on policy goals.

Ministers know they need to make tangible progress on key pledges before the next election, but Conservative MPs are far from united on flagship issues like ‘levelling up’ or net zero. That is clear from the proliferation of backbench groups like the Net Zero Scrutiny Group, drawing on the influence of the earlier European Research Group and Covid Recovery Group. Internal differences on policy means legislation on these matters tricky for the government – and a rebellious and unhappy parliamentary party will only make things harder.

Resetting – if only partially – the government’s parliamentary operation is a start. But unless this is accompanied by a recognition of changing backbench dynamics, and a greater willingness to meaningfully listen to MPs from across the parliamentary party, then the government’s agenda may yet be derailed.

- Keywords

- Parliamentary scrutiny

- Political party

- Conservative

- Position

- Whips

- Administration

- Johnson government

- Department

- Whips' Office

- Legislature

- House of Commons

- Public figures

- Chris Heaton-Harris Boris Johnson

- Publisher

- Institute for Government