While UK politicians have been in full election swing, Brussels has been busy preparing for the Brexit negotiations. It is the EU’s proposals that will now start to shape the debate, writes Anton Spisak.

The Brexit negotiations will kick off only 10 days after the election, almost one year after the UK’s decision to leave the EU. Theresa May called the election to strengthen her hand in talks with Brussels, but the Brexit election has failed to clarify much on the UK’s negotiating position, while eating up the Government’s valuable preparation time.

Meanwhile in Brussels, the EU has been getting its house in order.

After the EU’s heads of state and government agreed their negotiating guidelines in April, an arcane body of the EU’s 27 ministers – known as the General Affairs Council – has adopted detailed, legally binding instructions for Michel Barnier, the EU’s chief Brexit negotiator, on the divorce phase of the negotiations. Barnier later released two draft position papers setting out “essential principles” on citizens’ rights and money. All that while the European Council set out its transparency policy for negotiations.

When David Davis, the Brexit Secretary of State, triumphantly announced that the Government has “over 100 pages of detail” on Brexit in store, it must have left his Brussels counterpart satisfied – not least because the EU has published more than 100 pages of its own Brexit priorities since the UK triggered the Article 50 in March.

So, what have we learnt about negotiations from the EU’s pile of papers?

Expect the row of the summer

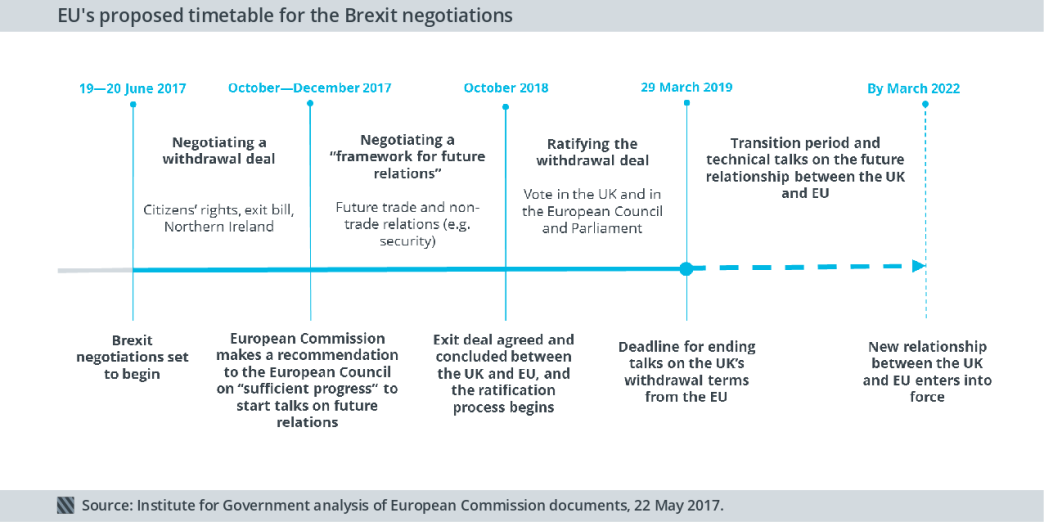

Brussels will kick off talks with a hard-line opening position on a technical but important matter: the timetable. The EU insists that talks must proceed in strictly defined sequences, requiring “sufficient progress” on settling the past before discussing the shape of future relations.

Barnier says this structure is “a key point” for ensuring smooth negotiations. It is, however, directly at odds with Westminster’s view of negotiations. David Davis has warned that the EU’s timetable will be the “row of the summer”.

Cutting a divorce deal will be an arduous undertaking

In recent weeks, the EU hardened its stance on Britain’s financial liabilities, legacy obligations from its EU membership and citizens’ rights, with Barnier warning that failure to agree on these issues would make a walkout from the negotiations “real”.

In its new negotiating directives, the EU has taken a maximalist view of Britain’s financial obligations – covering not only outstanding budget commitments, pensions and contingent liabilities, but also other costs such as relocating UK-based EU agencies, EU farm payments until 2020 and funding British teachers seconded to European schools until 2021.

While Barnier is clear the EU will not seek upfront agreement on a final exit bill, detailed principles on the UK’s financial obligations must be agreed early in the talks and cannot be reopened at a later stage.

Similarly, Brussels is demanding more on citizens’ rights. What the UK sees as a straightforward matter will prove more complicated. The first tricky issue to resolve is the EU’s insistence to maintain not only the residence rights of three million EU residents in the UK, but also their wider rights on “work, social security and health” and to be joined by spouse or family. The second problem is that Brussels wants those rights to be enforced by the European Court of Justice, or an equivalent body.

Slow Brexit: Take it in the right order and get what you want

Theresa May made clear her ambition to negotiate a “deep and ambitious” free trade agreement with the EU. Barnier shares this, saying in a recent speech in Brussels that the future trade deal should “be unlike any existing one.”

But they disagree on how to get there. In Brussels’ view, negotiating the future trade deal is possible only if the UK sticks to the EU’s timetable for the talks.

Barnier has in recent weeks fleshed out this timetable: the divorce issues should be settled by October or November, followed by negotiating “the framework for future relations” and a transitional agreement in the first half of 2018. This will leave enough time for ratifying the exit deal, while putting aside the discussions of the intricacies of future relations – not least on trade and regulatory issues – for after the UK’s formal departure in March 2019.

Brussels machine is setting the tone

The EU is also choosing to conduct negotiations in a “full transparency regime”, making most negotiating documents, position papers and agendas public on its website. This stands in stark contrast with the UK’s self-imposed vow of secrecy. As we have argued, transparency allows Brussels to control the public narrative around Brexit and strengthen its hand by reducing room for manoeuvre.

No wonder, with all that preparation of recent weeks, Barnier thinks the EU is “ready and well-prepared” to start talks with the UK. The EU officials have not left anything to chance for their first encounter with British counterparts on 19 June.

Whoever enters Downing Street on Friday morning will have to quickly swap bland electoral platitudes for concrete proposals on policy and assign key responsibilities for the negotiations. Failure to do so would be too costly for the new Prime Minister.