State aid rules after Brexit

The UK will be bound by the EU’s state aid rules until the end of the Brexit transition period.

The European Union’s (EU) restrictions on member states’ use of state aid were put in place to ensure that government resources are not used to distort competition between member states. Such limits on state spending are unique in the world: they go further than comparable anti-subsidy rules that bind other members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) or rules of other economic blocs.

The UK will be bound by the EU’s state aid rules until the end of the Brexit transition period. Thereafter, it could adopt a different approach, depending on the terms of a deal with the EU. Our report Beyond state aid: the future of subsidy control in the UK explores the UK’s options after 31 December.

What is state aid?

State aid is defined in the EU’s foundational treaty as any state spending that potentially distorts trade between member states. The measures must be selective (so country-wide tax measures are exempt but specific tax advantages to a subset of businesses are not) and they should benefit the recipient in some way.

The EU’s definition of ‘state aid’ is similar to the notion of a ‘subsidy’ used by the WTO’s Anti-subsidy and Countervailing Measures Agreement. However, state aid is a broader concept in that it covers virtually any kind of state spending whereas the WTO definition of a subsidy is more narrowly defined. In addition, in contrast to the WTO system, it is often only necessary to show that a subsidy might potentially harm trade between EU members for them to be deemed illegal under EU rules – as opposed to needing to show that actual harm has been done.

When are subsidies permitted under EU state aid rules?

While state aid is generally prohibited, the EU recognises that there can be valid reasons for governments to use it. The EU’s state aid rules therefore have some exemptions.

The main exemption is the General Block Exemption Regulation (GBER), which declares that certain categories of aid are automatically allowable. These categories include regional aid, training, subsidies for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and research and development (R&D), public infrastructure spending and environmental aid.

There is also a ‘de minimis’ rule, which means small subsidies (worth up to €200,000 over three consecutive years to one company) do not require sign-off from the European Commission.

Other exemptions can be granted at the Commission’s discretion on a case-by-case basis. But virtually all of the state aid within the EU (96%[1]) is covered by the GBER exemptions.

How are the EU’s state aid rules enforced?

The EU’s state aid rules are enforced by the European Commission and the courts of member states.

The Commission acts as an independent regulator with the power to decide whether a government intervention falls foul of the rules. All government policies that could constitute prohibited state aid need to be formally notified to the Commission in advance, with the exception of those covered by one of the exemptions. The Commission then judges whether the proposed subsidy should be allowed. To do this, it weighs up the likely impact on trade with the purported benefits of the aid. If it rules that the state aid is unlawful, the national courts of member states can enforce that judgment, often by requiring the recipient to pay back the support received in full.

If a government fails to notify the Commission in advance (for any reason) it can be challenged by private parties in its national courts. This can result in the beneficiary being ordered to repay the aid in full.

What subsidies do the UK and other EU member states offer to businesses?

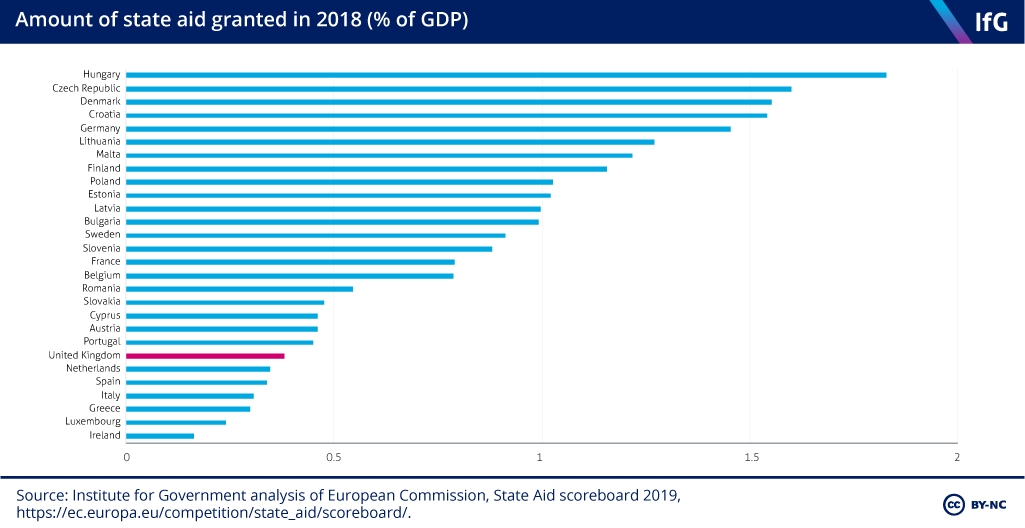

The EU’s state aid rules permit governments to offer some types of subsidies to business. The UK makes less use of these permissions than most member states. As the chart below shows, in 2017, the UK government spent 0.4% of GDP on state aid: this compares to an average of 0.7% across the EU as a whole – and a maximum of 6.7% in Sweden.

The state aid that the UK offers is mainly to promote environmental protection and energy saving (44%) and R&D activities (22%).

Has the UK’s economic response to coronavirus been limited by EU state aid rules?

The UK government – like others around the world – has responded to the coronavirus crisis by offering wide-ranging support to businesses. Its ability to do this has not been significantly limited by state aid rules, for two reasons.

First, many aspects of the economic support the UK offered do not meet the definition of state aid. For example, any universal support that is on offer to all businesses or individuals – such as the UK’s Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS, or ‘furlough’) or the deferral of payments of VAT – is outside the scope of the state aid rules.

Second, in March 2020, following the coronavirus outbreak the European Commission created a temporary framework for state aid. This lifted many of the usual constraints on targeted support. For example, Germany alone has so far granted 52% of all EU approved subsidies – roughly twice its share of EU GDP. The framework will be in place until December 2020 and all member states have had their state aid measures to deal with coronavirus approved in a matter of weeks – whereas the process usually takes months.

The temporary framework has meant that some UK measures, which would ordinarily have been against the rules, were approved. For example, in March, the Commission approved the UK’s Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBILS), which provides guarantees of up to 80% of loans for SMEs that could show they were not in financial difficulty in December 2019. Since then, the UK has also notified various other measures, including direct grants to companies.

How is state aid affecting the UK–EU talks?

State aid has emerged one of the major areas of disagreement between the UK and the EU in the future relationship negotiations.

The EU outlined its position on state aid in its negotiating objectives in February 2020 – arguing that a deal should include obligations for the UK to adopt EU state aid rules, with the European Court of Justice (ECJ) acting as the final arbiter of any disputes. In addition, for day-to-day operation of the system, the UK would need to set up a counterpart to the Commission to enforce the rules.

In contrast, the UK has offered to accept obligations similar to those provided in the EU’s trade deal with Canada (the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement, CETA). Those provisions do not do much more than reaffirm the commitments made in the WTO anti-subsidy agreement and provide for additional information sharing.

The EU argues that strong obligations on state aid between the UK and EU are warranted for two reasons. First, the size and proximity of the UK’s economy means the risk of UK subsidies harming EU trade is much greater than with other partners. Second, despite claims that it is asking for an ‘off-the-shelf agreement’, the UK is in fact asking for far freer access to EU markets than have been offered to the likes of Canada. The UK has rejected these arguments on the grounds that the EU’s position overstates the risk of harmful subsidies and is too restrictive of the UK’s future autonomy – specifically with regard to the role of the ECJ.

So far, the difference between the UK’s and the EU’s positions remains unresolved.

If there is no deal, will the UK be bound by the EU’s state aid rules after the end of the transition?

In the event that no deal is reached, the government has confirmed that there will be no replacement regime in place immediately after the transition period ends. However the UK will still be bound by the EU’s state aid rules to some extent because of provisions made in the Northern Ireland protocol (as agreed with the EU in January 2020 as part of the Withdrawal Agreement). A further complication to this is the government’s UK Internal Market Bill which gives powers for ministers to override the state aid provisions of the protocol.

According to the protocol, NI will continue to be subject to the EU’s state aid rules after January, although only in relation to goods, not services. The protocol makes clear that any measure that potentially impacts trade in goods between NI and the EU would be covered by EU state aid rules.

This broad test means that subsidies that are only supposed to apply in Great Britain could nonetheless be caught by the protocol. For example, if a retailer that has stores in both NI and GB receives a government subsidy in respect of its GB operations, its competitors in the Republic of Ireland (or the European Commission itself) could still argue that this falls under the jurisdiction of the state aid rules in the protocol. That would mean the subsidy would need to be notified to the Commission for approval.

The UK may use the powers in the UK Internal Market Bill to refuse to recognise the legal authority of the Commission. As a result, while under international law the UK will still be bound by state aid rules, it will have chosen to breach this obligation.

Will the UK set up its own subsidy-control regime?

The government has recently stated that if there is no deal there will be no system put in place, beyond the WTO requirements. The government will publish guidance on how to comply with these requirements. However, the statement also notes that the government will publish a consultation on whether it should go further than its international commitments. This implies that in the future the government will consider stronger obligations – though it is not clear whether this amount to anything like the obligations of state aid.

- European Commission, State aid: 2018 Scoreboard shows that over 96% of aid measures could be implemented quickly and without notifying the Commission in advance, press release, 24 January 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_19_663

- Topic

- Brexit Coronavirus

- Keywords

- Business Subsidy control

- Publisher

- Institute for Government